Old Church Slavonic

Historians credit the 9th-century Byzantine missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius with standardizing the language and undertaking the task of translating the Gospels and necessary liturgical books into it[9] as part of the Christianization of the Slavs.

It is generally held that the language was standardized by two Byzantine missionaries, Cyril and his brother Methodius, for a mission to Great Moravia (the territory of today's eastern Czech Republic and western Slovakia; for details, see Glagolitic alphabet).

[30] The mission took place in response to a request by Great Moravia's ruler, Duke Rastislav for the development of Slavonic liturgy.

[31] As part of preparations for the mission, in 862/863, the missionaries developed the Glagolitic alphabet and translated the most important prayers and liturgical books, including the Aprakos Evangeliar, the Psalter, and the Acts of the Apostles, allegedly basing the language on the Slavic dialect spoken in the hinterland of their hometown, Thessaloniki,[b] in present-day Greece.

Later texts written in each of those territories began to take on characteristics of the local Slavic vernaculars, and by the mid-11th century Old Church Slavonic had diversified into a number of regional varieties (known as recensions).

[52] A few sounds are given in Slavic transliterated form rather than in IPA, as the exact realisation is uncertain and often differs depending on the area that a text originated from.

Several notable constraints on the distribution of the phonemes can be identified, mostly resulting from the tendencies occurring within the Common Slavic period, such as intrasyllabic synharmony and the law of open syllables.

In addition, as a result of a process usually termed iotation (or iodization), velars and dentals alternate with palatals in various inflected forms and in word formation.

Though South Slavic in phonology and morphology, Old Church Slavonic was influenced by Byzantine Greek in syntax and style, and is characterized by complex subordinate sentence structures and participial constructions.

[57] Old Church Slavonic is valuable to historical linguists since it preserves archaic features believed to have once been common to all Slavic languages such as: Old Church Slavonic is also likely to have preserved an extremely archaic type of accentuation (probably close to the Chakavian dialect of modern Serbo-Croatian[citation needed]), but unfortunately, no accent marks appear in the written manuscripts.

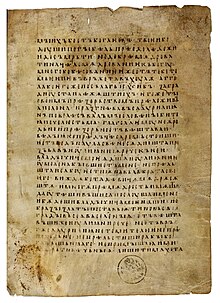

[61] More specifically, Old Church Slavonic is exemplified by extant manuscripts written between the 9th and 11th century in Great Moravia and the First Bulgarian Empire.

[62] The recension takes its name from the Slavic state of Great Moravia which existed in Central Europe during the 9th century on the territory of today's Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, northern Austria and southeastern Poland.

[63] It is preserved in religious texts (e.g. Prague Fragments), legends and glosses and shows substantial influence of the Western Slavic vernacular in Bohemia at the time.

Its main features are:[64] Although the missionary work of Constantine and Methodius took place in Great Moravia, it was in the First Bulgarian Empire that early Slavic written culture and liturgical literature really flourished.

[66][67][68] The language did not represent one regional dialect but a generalized form of early eastern South Slavic, which cannot be localized.

[69] The existence of two major literary centres in the Empire led in the period from the 9th to the 11th centuries to the emergence of two recensions (otherwise called "redactions"), termed "Eastern" and "Western" respectively.

[65][73][17] The development of Old Church Slavonic literacy had the effect of preventing the assimilation of the South Slavs into neighboring cultures, which promoted the formation of a distinct Bulgarian identity.

The main linguistic features of this recension include: Old Church Slavonic may have reached Slovenia as early as Cyril and Methodius's Panonian mission in 868 and is exemplified by the late 10th century Freising fragments, written in the Latin script.

[96] Old Church Slavonic in the Cyrillic script was in turn transmitted from Bulgaria to Serbia in the 10th century and to Kievan Rus' in connection with its adoption of Orthodox Christianity in 988.

[119] Instead of bringining the language closer to that of commoners, the "Euthymian", or Tarnovo, recension, rather sought to re-establish older Old Church Slavonic models, further archaizing it.

[120] The fall of Bulgaria under Ottoman rule in 1396 precipitated an exodus of Bulgarian men-of-letters, e.g., Cyprian, Gregory Tsamblak, Constantine of Kostenets, etc.

to Wallachia, Moldova and the Grand Duchies of Lithuania and Moscow, where they enforced the Euthymian recension as liturgical and chancery language, and to the Serbian Despotate, where it influenced the Resava School.

[123] The Russianization process was cut short in the late 1300s, when a series of Bulgarian prelates, starting with Cyprian, consciously "re-Bulgarized" church texts to achieve maximum conformity with the Euthymian recension.

The Euthymian recension that was pursued throughout the 1400s was gradually replaced in the 1500s by Ruthenian, an administrative language based on the Belarusian dialect of Vilno.

Primary features: Due to the Ottoman conquest of Bulgaria in 1396, Serbia saw an influx of educated scribes and clergy, who re-introduced a more classical form that resembled more closely the Bulgarian recension.

In the late 1400s and early 1500s, the Resava orthography spread to Bulgaria and North Macedonia and exerted substantial influence on Wallachia.

For example, the Freising Fragments, dating from the 10th century, show some linguistic and cultural traits of Old Church Slavonic, but they are usually not included in the canon, as some of the phonological features of the writings appear to belong to certain Pannonian Slavic dialect of the period.

On the other hand, the Kiev Missal is included in the canon even though it manifests some West Slavic features and contains Western liturgy because of the Bulgarian linguistic layer and connection to the Moravian mission.

With the exception of the Kiev Missal and Glagolita Clozianus, which exhibit West Slavic and Croatian features respectively, all Glagolitic texts are assumed to be of the Macedonian recension: All Cyrillic manuscripts are of the Preslav recension (Preslav Literary School) and date from the 11th century except for the Zographos, which is of the Ohrid recension (Ohrid Literary School): Here is the Lord's Prayer in Old Church Slavonic: The history of Old Church Slavonic writing includes a northern tradition begun by the mission to Great Moravia, including a short mission in the Lower Pannonia, and a Bulgarian tradition begun by some of the missionaries who relocated to Bulgaria after the expulsion from Great Moravia.

The full text of the Second Book of Enoch is only preserved in Old Church Slavonic, although the original most certainly had been in Greek or even Hebrew or Aramaic.