Ancient Rome and wine

The Roman belief that wine was a daily necessity made the drink "democratic" and ubiquitous; in various qualities, it was available to slaves, peasants and aristocrats, men and women alike.

Phillips estimates that on average, each member of Rome's urban population (man, woman or child) consumed half a litre of undiluted wine daily.

An expanse of farms and vineyards covered the slopes of nearby Vesuvius, exploiting its exceptionally fertile soil to produce some of the best wines available to the Italian mainland, Rome and the Provinces.

The wine shortage, and the potential for increased profits, led to the hurried planting of new vineyards nearer to Rome and the replanting of existing grain fields with grapevines.

During the Gallic Wars, when Julius Caesar brought his troops to Cabyllona in 59 BC, he found two Roman wine merchants already established in business trading with the local tribes.

In places like Bordeaux, Mainz, Trier and Colchester where Roman garrisons were established, vineyards were planted to supply local need and limit the cost of long-distance trading.

While it is possible that the Romans imported grapevines from Italy and Greece, there is sufficient evidence to suggest that they cultivated native vines that may be the ancestors of the grapes grown in those provinces today.

[clarification needed][16] Rome's defeat of Carthage in the Punic Wars brought the southern and coastal territories of Spain under its control, but the complete conquest of the Iberian Peninsula remained unaccomplished until the reign of Caesar Augustus.

While the Carthaginians and Phoenicians were the first to introduce viticulture to Spain, Rome's influential wine technology and the development of road networks brought new economic opportunities to the region, elevating grapes from a private agricultural crop to an important component of a viable commercial enterprise.

[18] In 2019, the oldest surviving liquid wine, dating to the 1st century, was discovered in the city of Carmona, Spain, part of Hispania Baetica, its contents were identified as a type of Sherry.

The extent to which the Celts and Gallic tribes produced wine is not clearly known, but the arrival of the Greeks near Massalia in 600 BC certainly introduced new types and styles of winemaking and viticulture.

In the 1st century AD, Pliny the Elder mentions plantings in Bordeaux, including the Balisca grape (previously known in Spain) under the synonym of Biturica after the local Bituriges tribe.

[21] Although wild V. vinifera vines have existed along the Rhine since prehistory, the earliest evidence of viticulture dates to the Roman conquest and settlement of the western territories of Germania.

Agricultural tools, such as pruning knives, have been found near Roman garrison posts in Trier and Cologne, but the first definitive record of wine production dates to the 370 AD work by Ausonius titled Mosella, wherein he described vibrant vineyards along the Mosel.

The reasons for planting Rhineland were to cater to the growing demand of Roman soldiers along the Limes Germanicus (German frontier) and the high costs associated with importing wine from Rome, Spain or Bordeaux.

Equestrian entrepreneurs often acted as agents and negotiators for landowners of the senatorial class, whose estates, large or small, were traditionally used to provide grain, olives and other food staples, not ingredients for luxuries such as wine production.

He had been raised on his family's farm in Reate, northeast of Rome, and wrote extensively on a variety of subjects in De agri cultura (Concerning the Cultivation of the Land), the oldest surviving work of Latin prose.

Published after Pliny's death near Pompeii following the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, the work covers a vast array of topics, including serious discourse on viticulture and wine.

Due to the dangers in working on and pruning vines trained this way, however, he advised not using slaves, who were costly to buy and maintain, but rather vineyard workers hired with a stipulation in their contract to cover grave and funeral expenses.

[33] Marcus Terentius Varro, whom the rhetorician Quintilian called "the most learned man among the Romans,"[34] wrote extensively on such topics as grammar, geography, religion, law and science, but only his agricultural treatise De re rustica (or Rerum rusticarum libri) has survived in its entirety.

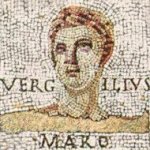

[35] The poetry of Virgil recalls that of the Greek poet Hesiod in its focus on the morality and virtue of viticulture, particularly the austerity, integrity and hard work of Roman farmers.

[1] Cato described the process of pressing as taking place in a special room that included an elevated concrete platform containing a shallow basin with raised curbs.

As the construction and use of a wine press was labor-intensive and expensive, its use was generally restricted to large estates, with smaller wineries relying on treading alone to obtain grape juice.

[45][46] The claimed prohibition and the consequences of its subversion have parallels in the myths pertaining to the "Women's goddess" Bona Dea, the nature deities Faunus and Fauna, and the founding of ancient Latium.

[48] The invention of wine was usually credited to Liber or his Greek equivalents, Bacchus (later Romanised) and Dionysus, who promoted the fertility of human and animal semen, and the "soft seed" of the vine.

[54] Early Roman culture was strongly influenced by the neighbouring Etruscans to the north, and the ancient Greek colonists of Southern Italy (Magna Graecia) both of whom exported wine, and held viticulture in high esteem.

In the 2nd century BC, Romans began to shift from meals consisting of moist porridge and gruel to those more bread-based; wine aided in eating the drier food.

They were originally occasional, women-only affairs, but became increasingly popular and frequent, and were opened to priests and initiates of both genders and all classes; they may have briefly supplanted an existing, lawful cult to Liber.

Wine was a recommended cure for mental disorders such as depression, memory loss and grief, as well as bodily ailments, from bloating, constipation, diarrhea, gout, and halitosis to snakebites, tapeworms, urinary problems and vertigo.

The Roman politician Cicero frequently labeled his rivals drunkards and a danger to Rome—most notably Mark Antony, who apparently once drank to such excess that he vomited in the Senate.