Opponent process

Ewald Hering first defined the unique hues as red, green, blue, and yellow, and based them on the concept that these colors could not be simultaneously perceived.

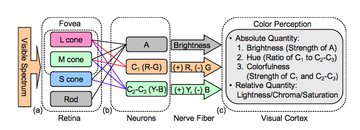

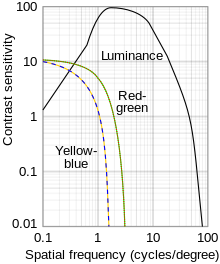

Retinal ganglion cells carry the information from the retina to the LGN, which contains three major classes of layers:[7] Transmitting information in opponent-channel color space is advantageous over transmitting it in LMS color space ("raw" signals from each cone type).

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe first studied the physiological effect of opposed colors in his Theory of Colours in 1810.

[8] Goethe arranged his color wheel symmetrically "for the colours diametrically opposed to each other in this diagram are those which reciprocally evoke each other in the eye.

Thus, yellow demands purple; orange, blue; red, green; and vice versa: Thus again all intermediate gradations reciprocally evoke each other.

Similar chromatically or spectrally opposed cells, often incorporating spatial opponency (e.g. red "on" center and green "off" surround), were found in the vertebrate retina and lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) through the 1950s and 1960s by De Valois et al.,[15] Wiesel and Hubel,[16] and others.

Others have applied the idea of opposing stimulations beyond visual systems, described in the article on opponent-process theory.

In 1967, Rod Grigg extended the concept to reflect a wide range of opponent processes in biological systems.

[25] In 1970, Solomon and Corbit expanded Hurvich and Jameson's general neurological opponent process model to explain emotion, drug addiction, and work motivation.

Critics and researchers have instead started to turn to explain color vision through references to retinal mechanisms, rather than opponent processing, which happens in the brain's visual cortex.

For instance, Jameson and D’Andrade[32] analyzed opponent-colors theory and found the unique hues did not match the spectrally opposed responses.

Despite evidence to the contrary ... textbooks have, up to this day, repeated the misconception of relating unique hue perception directly to peripheral cone opponent processes.

More recent experiments show that the relationship between the responses of single "color-opponent" cells and perceptual color opponency is even more complex than supposed.

An example of the complementary process can be experienced by staring at a red (or green) square for forty seconds, and then immediately looking at a white sheet of paper.