Orbit

For most situations, orbital motion is adequately approximated by Newtonian mechanics, which explains gravity as a force obeying an inverse-square law.

Historically, the apparent motions of the planets were described by European and Arabic philosophers using the idea of celestial spheres.

[4][5] The basis for the modern understanding of orbits was first formulated by Johannes Kepler whose results are summarised in his three laws of planetary motion.

Joseph-Louis Lagrange developed a new approach to Newtonian mechanics emphasizing energy more than force, and made progress on the three-body problem, discovering the Lagrangian points.

In a dramatic vindication of classical mechanics, in 1846 Urbain Le Verrier was able to predict the position of Neptune based on unexplained perturbations in the orbit of Uranus.

This led astronomers to recognize that Newtonian mechanics did not provide the highest accuracy in understanding orbits.

In relativity theory, orbits follow geodesic trajectories which are usually approximated very well by the Newtonian predictions (except where there are very strong gravity fields and very high speeds) but the differences are measurable.

The original vindication of general relativity is that it was able to account for the remaining unexplained amount in precession of Mercury's perihelion first noted by Le Verrier.

If e.g., an elliptical orbit dips into dense air, the object will lose speed and re-enter (i.e. fall).

Occasionally a space craft will intentionally intercept the atmosphere, in an act commonly referred to as an aerobraking maneuver.

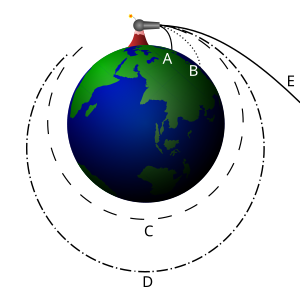

This is a 'thought experiment', in which a cannon on top of a tall mountain is able to fire a cannonball horizontally at any chosen muzzle speed.

The effects of air friction on the cannonball are ignored (or perhaps the mountain is high enough that the cannon is above the Earth's atmosphere, which is the same thing).

At a specific horizontal firing speed called escape velocity, dependent on the mass of the planet and the distance of the object from the barycenter, an open orbit (E) is achieved that has a parabolic path.

In a practical sense, both of these trajectory types mean the object is "breaking free" of the planet's gravity, and "going off into space" never to return.

In most situations, relativistic effects can be neglected, and Newton's laws give a sufficiently accurate description of motion.

To this Newtonian approximation, for a system of two-point masses or spherical bodies, only influenced by their mutual gravitation (called a two-body problem), their trajectories can be exactly calculated.

These can be formulated as follows: Note that while bound orbits of a point mass or a spherical body with a Newtonian gravitational field are closed ellipses, which repeat the same path exactly and indefinitely, any non-spherical or non-Newtonian effects (such as caused by the slight oblateness of the Earth, or by relativistic effects, thereby changing the gravitational field's behavior with distance) will cause the orbit's shape to depart from the closed ellipses characteristic of Newtonian two-body motion.

Except for special cases like the Lagrangian points, no method is known to solve the equations of motion for a system with four or more bodies.

Rather than an exact closed form solution, orbits with many bodies can be approximated with arbitrarily high accuracy.

These approximations take two forms: Differential simulations with large numbers of objects perform the calculations in a hierarchical pairwise fashion between centers of mass.

We assume that the central body is massive enough that it can be considered to be stationary and we ignore the more subtle effects of general relativity.

This resulting equation of the orbit of the object is that of an ellipse in Polar form relative to one of the focal points.

so the long axis of the ellipse is along the positive x coordinate we yield: When the two-body system is under the influence of torque, the angular momentum h is not a constant.

[10] The above classical (Newtonian) analysis of orbital mechanics assumes that the more subtle effects of general relativity, such as frame dragging and gravitational time dilation are negligible.

For example, the three numbers that specify the body's initial position, and the three values that specify its velocity will define a unique orbit that can be calculated forwards (or backwards) in time.

The time-averaged orbital distance is given by:[12] The analysis so far has been two dimensional; it turns out that an unperturbed orbit is two-dimensional in a plane fixed in space, and thus the extension to three dimensions requires simply rotating the two-dimensional plane into the required angle relative to the poles of the planetary body involved.

Some satellites with long conductive tethers can also experience orbital decay because of electromagnetic drag from the Earth's magnetic field.

Orbits can be artificially influenced through the use of rocket engines which change the kinetic energy of the body at some point in its path.

In the general case, the gravitational potential of a rotating body such as, e.g., a planet is usually expanded in multipoles accounting for the departures of it from spherical symmetry.

However, some special stable cases have been identified, including a planar figure-eight orbit occupied by three moving bodies.