Origin of the Moon

[3] The standard giant-impact hypothesis suggests that a Mars-sized body called Theia impacted the proto-Earth, creating a large debris ring around Earth, which then accreted to form the Moon.

Some theories have been stated that presume the proto-Earth had no large moons early in the formation of the Solar System, 4.425 billion years ago, Earth being basically rock and lava.

Some proportion of these ejecta escaped into space, but the rest consolidated into a single spherical body in orbit about Earth, creating the Moon.

Computer simulations show a need for a glancing blow, which causes a portion of the collider to form a long arm of material that then shears off.

The energy liberated during the reaccretion of material in orbit around Earth would have been sufficient to melt a large portion of the Moon, leading to the generation of a magma ocean.

[9][10][11] Although the giant-impact hypothesis explains many aspects of the Earth–Moon system, there are still a few unresolved problems, such as the Moon's volatile elements not being as depleted as expected from such an energetic impact.

[4] Surprisingly, the Apollo lunar samples carried an isotopic signature identical to Earth rocks, but different from other Solar System bodies.

However, such models struggle to explain the similar isotopic compositions of Earth and lunar rocks at the same time as the system's angular momentum, and the details of potential impact scenarios are hotly debated.

Above a high resolution threshold for simulations, a study published in 2022 finds that giant impacts can immediately place a satellite with similar mass and iron content to the Moon into orbit far outside Earth's Roche limit.

Even satellites that initially pass within the Roche limit can reliably and predictably survive, by being partially stripped and then torqued onto wider, stable orbits.

[19] In general terms, the main idea of the model suggests that the Moon was formed as a result of a violent rain of large asteroids (1–100 km) that repeatedly hammered the fledgling Earth over millions of years.

[17][19] In 2018, researchers at Harvard and UC Davis developed computer models demonstrating that one possible outcome of a planetary collision is that it creates a synestia, a mass of vaporized rock and metal which forms a biconcave disc extending beyond the lunar orbit.

Dutch scientists Rob de Meijer and Wim van Westrenen suggested in 2010 that the Moon may have formed from a nuclear explosion caused by the centrifugal force of an earlier, spinning proto-Earth.

The centrifugal force would have concentrated heavy elements such as thorium and uranium on the equatorial plane and at the boundary between the Earth's outer core and mantle.

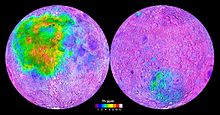

[35][36] A team of researchers of the Miniature Radio Frequency (Mini-RF) instrument on NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) spacecraft concluded that the Moon's subsurface may be richer in metals, like iron and titanium, more than scientists had believed.