Owenism

"Utopian socialist" economic thought such as Owen's was a reaction to the laissez-faire impetus of Malthusian Poor Law reform.

Claeys notes that "Owen’s 'Plan' began as a grandiose but otherwise not exceptionally unusual workhouse scheme to place the unemployed poor in newly built rural communities.

"[2] Owen’s "plan" was itself derivative of (and ultimately popularized by) a number of Irish and English trade unionists such as William Thompson and Thomas Hodgskin, co-founder of the London Mechanics Institute.

When this poverty led to revolt, as it did in Glasgow in April 1820, a "committee of gentlemen" from the area commissioned the cotton manufacturer and philanthropist, Robert Owen, to produce a "Report to the County of Lanark" in May 1820, which recommended a new form of pauper relief; the cooperative village.

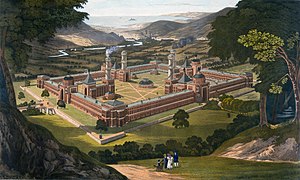

Owen's villages thus needed to be compared with the Dickensian "Houses of Industry" that were created after the passage of the 1834 Poor Law amendment act.

Owen was no theoretician, and the Owenite movement drew on a broad range of thinkers such as William Thompson, John Gray, Abram Combe, Robert Dale Owen, George Mudie, John Francis Bray, Dr William King, and Josiah Warren.

For example, the Edinburgh Practical Society created by the founders of Orbiston operated a co-operative store to raise the capital for the community.

Abram Combe, the leader of that community, was to author the pamphlet The Sphere for Joint Stock Companies (1825), which made clear that Orbiston was not to be a self-subsistent commune, but a co-operative trading endeavor.

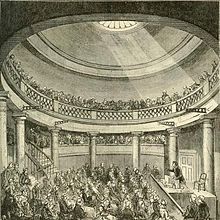

[16] The National Equitable Labour Exchange was founded in London in 1832 and spread to several English cities, most notably Birmingham, before closing in 1834.

A similar time-based currency would be created by an American Owenite, Josiah Warren, who founded the Cincinnati Time Store.

Between 1829 and 1835, Owenite socialism was politicized through two organizations; the British Association for the Promotion of Co-operative Knowledge, and its successor, the National Union of the Working Classes (founded in 1831, and abandoned in 1835).

It was from this heady mix of working class trade unionism, co-operativism, and political radicalism in the disappointed wake of the 1832 Reform Bill and the 1834 New Poor Law, that a number of prominent Owenite leaders such as William Lovett, John Cleave and Henry Hetherington helped form the London Working Men's Association in 1836.

Deep in debt, he was unable to return to Canada, and spent the succeeding five years preaching in London's workhouses and prisons.

[26] Osgood's proposal elicited support from across Upper Canada in early 1836, and petitions for the Relief Union's incorporation were sent to the Assembly and Legislative Council.

[27] In Chapter III of The Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx analyzes Owenism as a species of utopian socialism that developed in the "early undeveloped period" of the struggle between the bourgeoisie and proletariat— and that formerly put out literature "full of the most valuable materials for the enlightenment of the working class".

However, Marx interprets Owenism as having, by the time of his writing in 1848, parted ways with Chartism to become a "reactionary sect" that is "compelled to appeal to the feelings and purses of the bourgeois class" to receive the funding necessary for utopian communities or other projects.