Pacha (Inca mythology)

This latter interpretation, disputed by some scholars since such realm names may have been the product of missionaries' lexical innovation (and, thus, of Christian influence), is considered to refer to "real, concrete places, and not ethereal otherworlds".

[17] In the pre-Columbian Andean world, the conception of time was associated with space, both collectively called pacha (earth, soil), which was in continual development toward order and toward "functional differentiation and discontinuity of forms, factors of complementarity rather than rivalry, therefore of peace and productivity".

[2][14] There existed various geographic spatio-temporel divisions, with strong political and ideological connotations, in Cuzco and in the Inca Empire, showing the social status and position of groups and places, and influencing the administrative organization of the Andean chiefdoms.

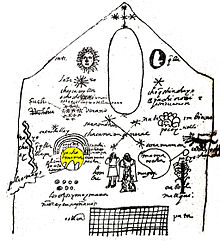

[3] The spatio-temporal development of the cosmos was divided into several fundamental stages in the development of the world: the pre-solar era, during which men lived in semi-darkness, which was closed by the event of the arrival of the sun, establishing the alternation between night and day; the solar era, divided into two periods by the advent of the great flood called Unu Pachacuti ("reversal of space-time, or return of time, by water"), a first period where the huacas ruled the Andean states, and a second during which the relations of opposition and complementarity were maintained between the llaqtas, urban spaces, and urqu, uninhabited lands of the mountains, the ancient huaca lords now personifying the natural spaces surrounding and defining the identity of the Andean socio-territorial and political entities; and then the Purum Pacha and the Inka Pacha, the first era being the pre-Incaic age supposedly uncultured and barbaric, and the second being the Incaic era, in which, following the conquests of the Inca Emperor Pachacuti ("world's turning" or "cataclysm") which mark a "sort of "return to square one", after exhaustion of the forces [camaquen] of the era which was ending" and which then became the old era associated with chaos, the Inca empire is charged of the civilizing and ordering mission of the post-diluvian world,[1] notably in order to delay the end and the cyclical restarting of the world.

This concept of duality considered everything which existed as having two opposed complementary characteristics ( feminine and masculine, hot and cold, positive and negative, dark and light, order and chaos, etc.).

"upper pacha"),[27] used for "heaven" in colonial sources, is interpreted as the original name of a cosmological realm that would have included the sky, the sun, the moon, the stars, the planets, and constellations (of particular importance being the milky way).

This latter word was used by missionaries to describe Satan, but is interpreted by many anthropologists as the pre-Hispanic name of demon-like creatures which would have tormented the living.

[33] Human disruptions of the ukhu pacha may have been considered a sacred matter, and ceremonies and rituals were often associated with disturbances of the surface.

[citation needed] In Inca custom, during the time of tilling for potato crops the disturbance of the soil was met with a host of sacred rituals.

Kendall W. Brown contends that the dualistic nature and rituals surrounding openings to ukhu pacha may have made it easier to initially get indigenous laborers to work in the mines.

This chronicler, writing in a particular political context, thought, similarly to Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, that the Inca emperors prepared the Andes to receive Catholicism, comparing events from Andean cosmological development to Western history, notably using the word "flood" to describe Unu Pachacuti, and therefore comparing the destruction of the world by the creator deity Viracocha to the Bliblical flood.

[36] The archeologist Pierre Duviols notes that Guaman Poma, adopting a Western way of thinking, used, along with other chroniclers, the concept of "ages", to describe supposed cycles, which was an important part of Ancient Greek thought.

[37] Furthermore, the Peruvian linguist Rodolfo Cerrón Palomino attributes the coining of the compounds entirely to Catholic missionaries' lexical planning.

[38] According to these criticisms, the spatial-temporal concept of pacha as "era", "stage" or "realm" would be an unjustified anachronistic attribution of Christian beliefs to Andean pre-Hispanic societies.