Crystal Cubism

As post-war reconstruction began, so too did a series of exhibitions at Léonce Rosenberg's Galerie de L'Effort Moderne: order and the allegiance to the aesthetically pure remained the prevailing tendency.

[3] Crystal Cubism, and its associative rappel à l’ordre, has been linked with an inclination—by those who served the armed forces and by those who remained in the civilian sector—to escape the realities of the Great War, both during and directly following the conflict.

In a letter addressed to Émile Bernard dated 15 April 1904, Cézanne writes: "Interpret nature in terms of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone; put everything in perspective, so that each side of an object, of a plane, recedes toward a central point.

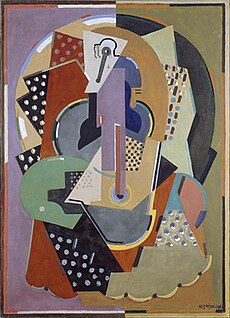

[7] By 1907, representational form gave way to a new complexity; subject matter progressively became dominated by a network of interconnected geometric planes, the distinction between foreground and background no longer sharply delineated, and the depth of field limited.

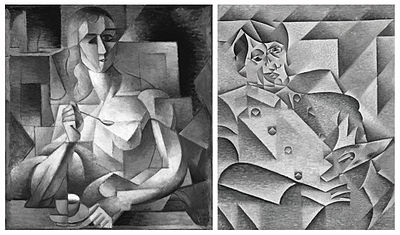

[8] From the 1911 Salon des Indépendants, an exhibition which officially introduced "Cubism" to the public as an organized group movement, and extending through 1913, the fine arts had evolved well beyond the teachings of Cézanne.

[4] The evolution towards rectilinearity and simplified forms continued through 1909 with greater emphasis on clear geometric principles; visible in the works of Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Henri Le Fauconnier and Robert Delaunay.

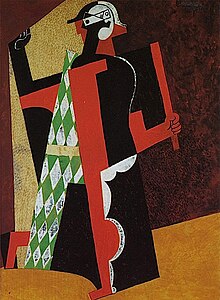

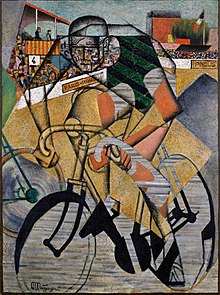

; Fernand Léger Le modèle nu dans l'atelier; Juan Gris L'Homme au Café; and Albert Gleizes Les Joueurs de football.

[2] Crystal Cubism also coincided with the emergence of a methodical framework of theoretical essays on the topic,[2] by Albert Gleizes, Juan Gris, Fernand Léger, Gino Severini, Pierre Reverdy, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, and Maurice Raynal.

[1] Even before Raynal coined the term Crystal Cubism, one critic by the name of Aloës Duarvel, writing in L'Elan, referred to Metzinger's entry exhibited at Galerie Bernheim-Jeune as 'jewellery' ("joaillerie").

[22] During the year 1916, Sunday discussions at the studio of Lipchitz, included Metzinger, Gris, Picasso, Diego Rivera, Henri Matisse, Amedeo Modigliani, Pierre Reverdy, André Salmon, Max Jacob, and Blaise Cendrars.

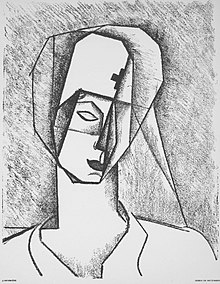

[23] In a letter written in Paris by Metzinger to Albert Gleizes in Barcelona during the war, dated 4 July 1916, he writes: After two years of study I have succeeded in establishing the basis of this new perspective I have talked about so much.

Vacating these non-essential features would lead Metzinger on a path towards Soldier at a Game of Chess (1914–15), and a host of other works created after the artist's demobilization as a medical orderly during the war, such as L'infirmière (The Nurse) location unknown, and Femme au miroir, private collection.

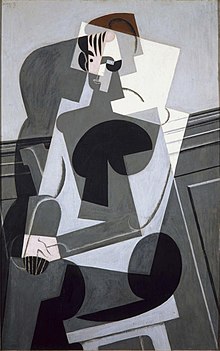

In 1916, drawing from black and white postcards representing works by Corot, Velázquez and Cézanne, Gris created a series of classical (traditionalist) Cubist figure paintings, employing a purified range of pictorial and structural features.

[1] The clear-cut underlying geometric framework of these works seemingly control the finer elements of the compositions; the constituent components, including the small planes of the faces, become part of the unified whole.

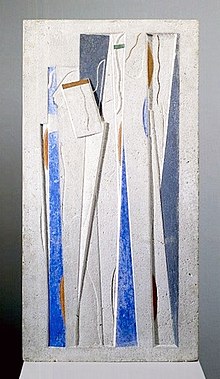

Csaky's polychrome reliefs of the early 1920s display an affinity with Purism—an extreme form of the Cubism aesthetic developing at the time—in their rigorous economy of architectonic symbols and the use of crystalline geometric structures.

In 1921 Rosenberg organized an exhibit titled Les maîtres du Cubisme, a group show that featured works by Csaky, Gleizes, Metzinger, Mondrian, Gris, Léger, Picasso, Laurens, Braque, Herbin, Severini, Valmier, Ozenfant and Survage.

They reflect a collective spirit of the time, "a puritanical denial of sensuousness that reduced the cubist vocabulary to rectangles, verticals, horizontals," writes Balas, "a Spartan alliance of discipline and strength" to which Csaky adhered in his Tower Figures.

"In their aesthetic order, lucidity, classical precision, emotional neutrality, and remoteness from visible reality, they should be considered stylistically and historically as belonging to the De Stijl movement."

[46] Both Lipchitz and Laurens retained highly figurative and legible components in their works leading up to 1915-16, after which naturalist and descriptive elements were muted, dominated by a synthetic style of Cubism under the influence of Picasso and Gris.

With observed reality no longer the basis for the depiction of subject, model or motif, Lipchitz and Laurens created works that excluded any starting point, based predominantly on the imagination, and continued to do so during the transition from war to peace.

[51] Reverdy began this project towards the end of 1916, with an art world still under the pressures of war, to show the parallels between the poetic theories of Guillaume Apollinaire of Max Jacob and himself in marking the burgeoning of a new era for poetry and artistic reflection.

This is nothing basically but a ruse, because Pinturrichichio [sic], of the Carnet de la Semaine and the others know very well that the serious artists of this group are extremely happy to see go... those opportunists who have taken over creations the significance of which they do not even comprehend, and were attracted only by the love of buzz and personal interest.

Nonetheless, according to Christopher Green, "this was an astonishingly complete demonstration that Cubism had not only continued between 1914 and 1917, having survived the war, but was still developing in 1918 and 1919 in its "new collective form" marked by "intellectual rigor".

(Jean Metzinger, November 1923)[55]Further evidence to bolster the prediction made by Vauxcelles could have been found in a small exhibition at the Galerie Thomas (in a space owned by a sister of Paul Poiret, Germaine Bongard [fr]).

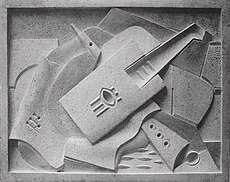

The first exhibition of Purist Art opened on 21 December 1918, with works by Amédée Ozenfant and Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (later called Le Corbusier), who claimed to be successors of pre-war Cubism.

Some of the works exhibited related directly to the Cubism practiced during the war (such as Ozenfant's Bottle, Pipe and Books, 1918), with flattened planar structures and varying degrees of multiple perspective.

In the last issue, Jeanneret, under the pseudonym Paul Boulard, writes of how the laws of nature were manifested in the shape of crystals; the properties of which were hermetically coherent, both interiorly and exteriorly.

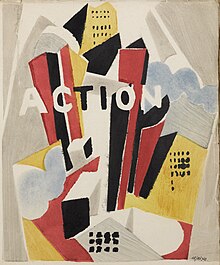

[73] This work, a precursor to Crystal Cubism, consists of broad, overlapping planes of brilliant color, dynamically intersecting vertical, diagonal, horizontal lines coupled with circular movements.

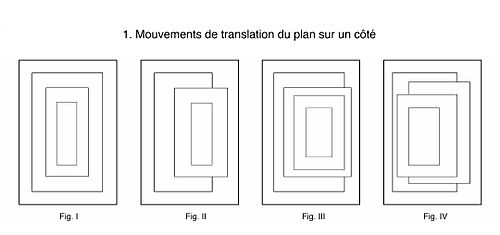

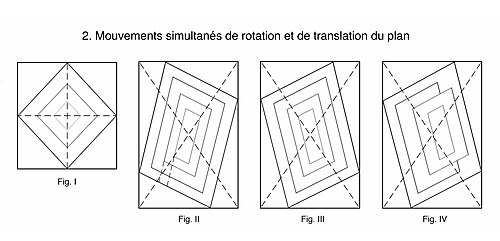

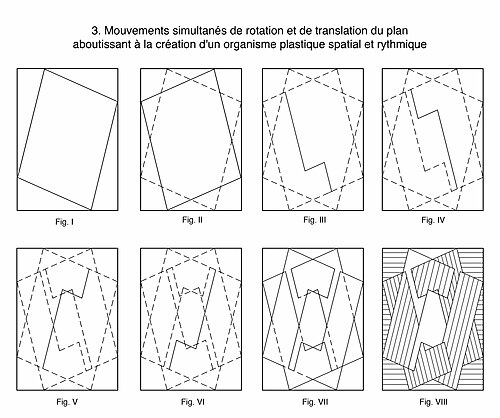

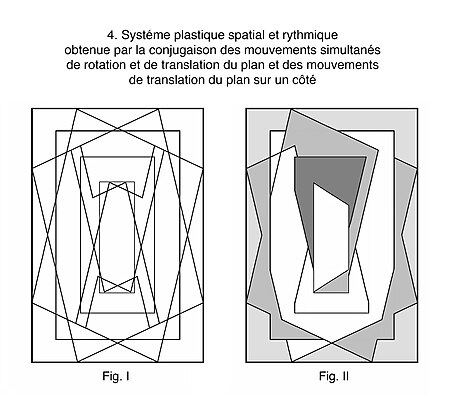

[79][80] With these figures Gleizes attempts to present, under the most simple conditions possible (simultaneous movements of rotation and translation of the plane), the creation of a spatial and rhythmic organism (Fig.

[79][80] Throughout the war, to Armistice of 11 November 1918 and the series of exhibitions at Galerie de L'Effort Moderne that followed, the rift between art and life—and the overt distillation that came with it—had become the canon of Cubist orthodoxy; and it would persist despite its antagonists through the 1920s:[1] Order remained the keynote as post-war reconstruction commenced.