Papillomaviridae

[1] Several hundred species of papillomaviruses, traditionally referred to as "types",[2] have been identified infecting all carefully inspected mammals,[2] but also other vertebrates such as birds, snakes, turtles and fish.

All known papillomavirus types infect a particular body surface,[2] typically the skin or mucosal epithelium of the genitals, anus, mouth, or airways.

Papillomaviruses were first identified in the early 20th century, when it was shown that skin warts, or papillomas, could be transmitted between individuals by a filterable infectious agent.

In 1935 Francis Peyton Rous, who had previously demonstrated the existence of a cancer-causing sarcoma virus in chickens, went on to show that a papillomavirus could cause skin cancer in infected rabbits.

[13] Phylogenetic studies strongly suggest that PVs normally evolve together with their mammalian and bird host species, but adaptive radiations, occasional zoonotic events and recombinations may also impact their diversification.

This new taxonomic system does not affect the traditional identification and characterization of PV "types" and their independent isolates with minor genomic differences, referred to as "subtypes" and "variants", all of which are taxa below the level of "species".

[citation needed] Individual papillomavirus types tend to be highly adapted to replication in a single animal species.

In one study, researchers swabbed the forehead skin of a variety of zoo animals and used PCR to amplify any papillomavirus DNA that might be present.

However, the authors note that the chimpanzee-specific papillomavirus sequence could have been the result of surface contamination of the zookeeper's skin, as opposed to productive infection.

[citation needed] A few reports have identified papillomaviruses in smaller rodents, such as Syrian hamsters, the African multimammate rat and the Eurasian harvest mouse.

[citation needed] It is believed that papillomaviruses generally co-evolve with a particular species of host animal over many years, although there are strong evidences against the hypothesis of coevolution.

[26][27] Cutaneotropic HPV types are occasionally exchanged between family members during the entire lifetime, but other donors should also be considered in viral transmission.

[29] It is not clear whether this similarity is due to recent transmission between species or because HPV-13 has simply changed very little in the six or so million years since humans and bonobos diverged.

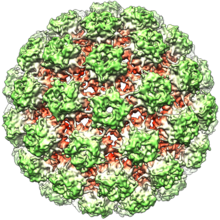

[citation needed] Papillomaviruses are non-enveloped, meaning that the outer shell or capsid of the virus is not covered by a lipid membrane.

Less-differentiated keratinocyte stem cells, replenished on the surface layer, are thought to be the initial target of productive papillomavirus infections.

[citation needed] Papillomaviruses gain access to keratinocyte stem cells through small wounds, known as microtraumas, in the skin or mucosal surface.

[33][34] The virus is then able to get inside from the cell surface via interaction with a specific receptor, likely via the alpha-6 beta-4 integrin,[35][36] and transported to membrane-enclosed vesicles called endosomes.

[37][38] The capsid protein L2 disrupts the membrane of the endosome through a cationic cell-penetrating peptide, allowing the viral genome to escape and traffic, along with L2, to the cell nucleus.

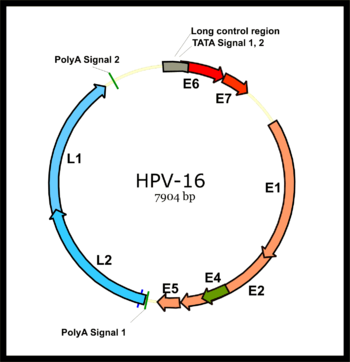

[42] The expression of the viral late genes, L1 and L2, is exclusively restricted to differentiating keratinocytes in the outermost layers of the skin or mucosal surface.

Because infectious BPV-1 virions can be extracted from the large warts the virus induces on cattle, it has been a workhorse model papillomavirus type for many years.

[48] Some sexually transmitted HPV types have been propagated using a mouse "xenograft" system, in which HPV-infected human cells are implanted into immunodeficient mice.

For example, E2-dependent transcription, genome amplification and efficient encapsidation of full-length HPV DNAs can be easily recreated in yeast (Angeletti 2005).

Studies have shown that the crystal of isolated L1 capsomeres has the heparin chains recognized by lysines lines grooves on the surface of the virus.

This represents a dramatic difference between papillomaviruses and polyomaviruses, since the latter virus type expresses its early and late genes by bi-directional transcription of both DNA strands.

This difference was a major factor in establishment of the consensus that papillomaviruses and polyomaviruses probably never shared a common ancestor, despite the striking similarities in the structures of their virions.

The E2 protein serves as a master transcriptional regulator for viral promoters located primarily in the long control region.

[57] The E4 protein of many papillomavirus types is thought to facilitate virion release into the environment by disrupting intermediate filaments of the keratinocyte cytoskeleton.

The E5 proteins of human papillomaviruses associated to cancer, however, seem to activate the signal cascade initiated by epidermal growth factor upon ligand binding.

[69] In addition to cooperating with L1 to package the viral DNA into the virion, L2 has been shown to interact with a number of cellular proteins during the infectious entry process.

After endosome escape, L2 and the viral genome are imported into the cell nucleus where they traffic to a sub-nuclear domain known as an ND-10 body that is rich in transcription factors.