Paragliding

[2] In 1954, Walter Neumark predicted (in an article in Flight magazine) a time when a glider pilot would be "able to launch himself by running over the edge of a cliff or down a slope ... whether on a rock-climbing holiday in Skye or skiing in the Alps.

These developments were combined in June 1978 by three friends, Jean-Claude Bétemps, André Bohn and Gérard Bosson, from Mieussy, Haute-Savoie, France.

[13][14] In modern paragliders, semi-flexible rods made out of plastic or nitinol are used to give extra stability to the profile of the wing.

High-performance paragliders meant for competitions may achieve faster accelerated flight,[19] as do speedwings, due to their small size and different profile.

Most harnesses have protectors made out of foam or other materials underneath the seat and behind the back to reduce the impact on failed launches or landings.

While pod harnesses offer more stability and aerodynamic properties, they increase the risk of riser twist, and are hence not suitable for beginners.

GNSS is also used to determine drift due to the prevailing wind when flying at altitude, providing position information to allow restricted airspace to be avoided and identifying one's location for retrieval teams after landing out in unfamiliar territory.

It is highly recommended that low hour pilots, ground-handling, should be wearing a formal harness with leg and waist straps firmly fitted and fastened.

The ideal launch training site for novices with standard wings has the following characteristics: As pilots progress, they may challenge themselves by kiting over and around obstacles, in strong or turbulent wind, and on greater slopes.

Most pilots will find that when their hands are vertically under the brake line pulleys they are able reduce trailing edge drag to the absolute minimum.

Pilots line up into a position above the airfield and to the side of the landing area, which is dependent on the wind direction, where they can lose height (if necessary) by flying circles.

Landing involves lining up for an approach into wind and, just before touching down, flaring the wing to minimise vertical and/or horizontal speed.

This involves taking the leading edge lines (As) in each hand at the mallion/riser junction and applying the pilot's full weight with a deep knee bend action.

Promptly rotate to face down wind, maintain pressure on the rear risers and take brisk steps towards the wing as it falls.

For strong winds during the landing approach, flapping the wing (symmetrical pulsing of brakes) is a common option on final.

As a rule the manufacturer has set the safe-brake-travel-range based on average body proportions for pilots in the approved weight range.

Making changes to that setting should be undertaken in small increases, with tell-tale marks showing the variations and a test flight to confirm the desired effect.

While they are held-in the wing tends to respond to weight shift slightly better (due to reduced effective area) on the roll axis.

The effect of sudden wind blasts can be countered by directly pulling on the risers and making the wing unflyable, thereby avoiding falls or unintentional takeoffs.

It places greater loads on the wing than other techniques do and requires the highest level of skill from the pilot to execute safely.

If the terrain is not uniform, it will warm some features more than others (such as rock faces or large buildings) and these thermals will tend to always form at the same spot, otherwise they will be more random.

Most pilots use a vario-altimeter ("vario"), which indicates climb rate with beeps and/or a visual display, to help core in on a thermal.

Cross-country pilots also need an intimate familiarity with air law, flying regulations, aviation maps indicating restricted airspace, etc.

In-flight wing deflation and other hazards are minimized by flying a suitable glider and choosing appropriate weather conditions and locations for the pilot's skill and experience level.

The use of proper equipment such as a wing designed for the pilot's size and skill level,[30] as well as a helmet, a reserve parachute,[31] and a cushioned harness[32] also minimize risk.

Pilot safety is influenced by an understanding of the site conditions such as air turbulence (rotors), strong thermals, gusty wind, and ground obstacles such as power lines.

These courses are typically led by a specially trained instructor over large bodies of water, with the student usually being instructed via radio.

Inspect the paragliding equipment for wear and tear, focusing on components like the canopy, brake lines, and reserve parachute, which should be regularly maintained.

Finally, confirm the operator's licenses and permissions, and practice ground handling skills under guidance before takeoff to enhance safety and control.

Whereas with sky diving the parachute is a tool to safely return to earth after free fall, the paraglider allows longer flights and the use of thermals.

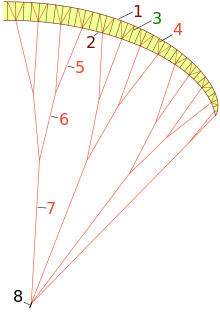

- upper surface

- lower surface

- rib

- diagonal rib

- upper line cascade

- middle line cascade

- lower line cascade

- risers