Parapatric speciation

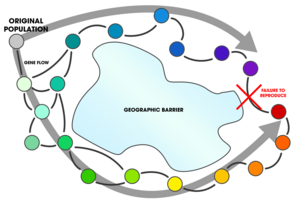

This distribution pattern may be the result of unequal dispersal, incomplete geographical barriers, or divergent expressions of behavior, among other things.

In biogeography, the terms parapatric and parapatry are often used to describe the relationship between organisms whose ranges do not significantly overlap but are immediately adjacent to each other; they do not occur together except in a narrow contact zone.

It was not until 1930, when Ronald Fisher published The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection where he outlined a verbal theoretical model of clinal speciation.

[1]: 124 Mathematical models, laboratory studies, and observational evidence supports the existence of parapatric speciation's occurrence in nature.

Some biologists reject this delineation, advocating the disuse of the term "parapatric" outright, "because many different spatial distributions can result in intermediate levels of gene flow".

[10][1]: 113 Further mathematical models have been developed to demonstrate the possibility of clinal speciation with most relying on, what Coyne and Orr assert are, "assumptions that are either restrictive or biologically unrealistic".

[1]: 113 A mathematical model for clinal speciation was developed by Caisse and Antonovics that found evidence that, "both genetic divergence and reproductive isolation may therefore occur between populations connected by gene flow".

Doebeli and Dieckmann developed a mathematical model that suggested that ecological contact is an important factor in parapatric speciation and that, despite gene flow acting as a barrier to divergence in the local population, disruptive selection drives assortative mating; eventually leading to a complete reduction in gene flow.

The authors conclude that, "spatially localized interactions along environmental gradients can facilitate speciation through frequency-dependent selection and result in patterns of geographical segregation between the emerging species.

[1]: 117 Ödeen and Florin complied 63 laboratory experiments conducted between the years 1950–2000 (many of which were discussed by Rice and Hostert previously[18]) concerning sympatric and parapatric speciation.

Particularly, documenting closely related species sharing common boundaries does not imply that parapatric speciation was the mode that created this geographic distribution pattern.

This is described by the following criteria: This has been exemplified by the grass species Agrostis tenuis that grows on soil contaminated with high levels of copper, leached from an unused mine.

[22] Clines are often cited as evidence of parapatric speciation and numerous examples have been documented to exist in nature; many of which contain hybrid zones.

These clinal patterns, however, can also often be explained by allopatric speciation followed by a period of secondary contact—causing difficulty for researchers attempting to determine their origin.

[24] Jiggins and Mallet surveyed a range of literature documenting every phase of parapatric speciation in nature positing that it is both possible and likely (in the studied species discussed).

[27] In the Tennessee cave salamander, timing of migration was used to infer the differences in gene flow between cave-dwelling and surface-dwelling continuous populations.

Concentrated gene flow and mean migration time results inferred a heterogenetic distribution and continuous parapatric speciation between populations.

[28] Researchers studying Ephedra, a genus of gymnosperms in North American, found evidence of parapatric niche divergence for the sister species pairs E. californica and E.

[30] It is widely thought that parapatric speciation is far more common in oceanic species due to the low probability of the presence of full geographic barriers (required in allopatry).