Particulate organic matter

In addition to carbon, POM includes the mass of the other elements in the organic matter, such as nitrogen, oxygen and hydrogen.

[5][6] When sieving to determine POM content, consistency is crucial because isolated size fractions will depend on the force of agitation.

[7] POM is readily decomposable, serving many soil functions and providing terrestrial material to water bodies.

In water bodies, POM can contribute substantially to turbidity, limiting photic depth which can suppress primary productivity.

POM also enhances soil structure leading to increased water infiltration, aeration and resistance to erosion.

The biomass of living zooplankton is intentionally excluded from POC through the use of a pre-filter or specially designed sampling intakes that repel swimming organisms.

[18] As shown below, non-living organic matter in soils can be grouped into four distinct categories on the basis of size, behaviour and persistence.

Humus is the end product of soil organism activity, is chemically complex, and does not have recognisable characteristics of its origin.

[18] Resistant organic matter: has a high carbon content and includes charcoal, charred plant materials, graphite and coal.

[18] Particulate organic matter (POM) includes steadily decomposing plant litter and animal faeces, and the detritus from the activity of microorganisms.

[6] The amount of nutrients released (mineralized) during decomposition depends on the biological and chemical characteristics of the POM, such as the C:N ratio.

[6] In addition to nutrient release, decomposers colonizing POM play a role in improving soil structure.

[8] Because POM provides a source of energy and nutrients, rapid build-up of organic matter in water can result in eutrophication.

Optical instruments can be used from ships or installed on autonomous platforms, delivering much greater spatial and temporal coverage of particles in the mesopelagic zone of the ocean than traditional techniques, such as sediment traps.

Technologies to image particles have advanced greatly over the last two decades, but the quantitative translation of these immense datasets into biogeochemical properties remains a challenge.

In particular, advances are needed to enable the optimal translation of imaged objects into carbon content and sinking velocities.

The model shown in the diagram at the right attempts to capture some of the predominant features that influence the shape of the sinking flux profile (red line).

Particles raining out from the upper ocean undergo remineralization by bacteria colonized on their surface and interior, leading to an attenuation in the sinking flux of organic matter with depth.

[21] Marine snow varies in shape, size and character, ranging from individual cells to pellets and aggregates, most of which is rapidly colonized and consumed by heterotrophic bacteria, contributing to the attenuation of the sinking flux with depth.

Building on these expectations, many studies have tried to relate sinking velocity primarily to size, which has been shown to be a useful predictor for particles generated in controlled environments (e.g., roller tanks.

[42][25] Along with dissolved organic matter, POM drives the lower aquatic food web by providing energy in the form of carbohydrates, sugars, and other polymers that can be degraded.

POM in water bodies is derived from terrestrial inputs (e.g. soil organic matter, leaf litterfall), submerged or floating aquatic vegetation, or autochthonous production of algae (living or detrital).

Therefore, a central focus of marine organic geochemistry studies is to improve the understanding of POC distribution, composition, and cycling.

The last few decades have seen improvements in analytical techniques that have greatly expanded what can be measured, both in terms of organic compound structural diversity and isotopic composition, and complementary molecular omics studies.

[9] As illustrated in the diagram, phytoplankton fix carbon dioxide in the euphotic zone using solar energy and produce POC.

Any changes in its magnitude caused by a warming world may have direct implications for both deep-sea organisms and atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations.

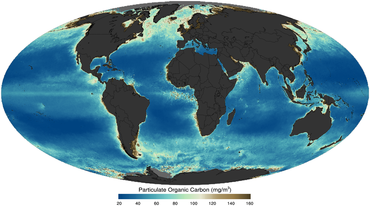

as imaged by satellite in 2011