Parylene

Parylene is the common name of a polymer whose backbone consists of para-benzenediyl rings −C6H4− connected by 1,2-ethanediyl bridges −CH2−CH2−.

Parylene is considered a "green" polymer because its polymerization needs no initiator or other chemicals to terminate the chain; and the coatings can be applied at or near room temperature, without any solvent.

He deposited parylene films by the thermal decomposition of [2.2]paracyclophane at temperatures exceeding 550 °C and in vacuum below 1 Torr.

Derivatives of parylene can be obtained by replacing hydrogen atoms on the phenyl ring or the aliphatic bridge by other functional groups.

A major disadvantage for many applications is its insolubility in any solvent at room temperature, which prevents removal of the coating when the part has to be re-worked.

Also, the chlorine on the phenyl ring of the parylene C repeat unit is problematic for RoHS compliance, especially for the printed circuit board manufacture.

Moreover, some of the dimer precursor is decomposed by breaking of the aryl-chlorine bond during pyrolysis, generating carbonaceous material that contaminates the coating, and hydrogen chloride HCl that may harm vacuum pumps and other equipment.

The free-radical (phenyl radical) generated in this process is not resonance-stabilized and mitigates the deposition of a parylene-like material on the downside of the pyrolysis tube.

This material becomes carbonized and generates particles in situ to contaminate clean rooms and create defects on printed-circuit boards that are often called "stringers and nodules".

Parylene AF-4 has been used to protect outdoor LED displays and lighting from water, salt and pollutants successfully.

Because of the aliphatic −CH2− units, it has poor oxidative and UV stability, but still better than N, C, or D. The hydrogen atoms can be replaced also by alkyl groups.

Another reactive variant is parylene X, which features an ethinyl group −C≡CH attached to the phenyl ring in some of the units.

This variant, which contains no elements other than hydrogen and carbon, can be cross-linked by heat or with UV light and can react with copper or silver salts to generate the corresponding metalorganic complexes Cu-acetylide or Ag-acetylide.

However, parylene AF-4 is more expensive due to a three-step synthesis of its precursor with low yield and poor deposition efficiency.

[13] This lack of solubility has made it difficult to re-work printed circuit boards coated with parylene.

As a moisture diffusion barrier, the efficacy of halogneated parylene coatings scales non-linearly with their density.

This method has one very strong benefit, namely it does not generate any byproducts besides the parylene polymer, which would need to be removed from the reaction chamber and could interfere with the polymerization.

[15] The process involves three steps: generation of the gaseous monomer, adsorption on the part's surface, and polymerization of adsorbed film.

[16][17] Many of the parylenes exhibit this selectivity based on quantum mechanical deactivation of the triplet state, including parylene X. Polymerization may proceed by a variety of routes that differ in the transient termination of the growing chains, such as a radical group −CH•2 or a negative anion group CH−2: The monomer polymerizes only after it is physically adsorbed (physisorbed) on the part's surface.

Another relevant property for the deposition process is polarizability, which determines how strongly the monomer interacts with the surface.

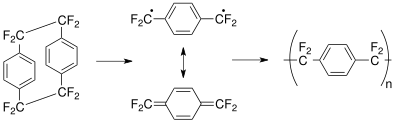

The p-xylylene monomer is normally generated during the coating process by evaporating the cyclic dimer [2.2]para-cyclophane at a relatively low temperature, then decomposing the vapor at 450–700 °C and pressure 0.01–1.0 Torr.

For example, parylene C can be obtained from the dimeric precursor dichloro[2.2]para-cyclophane, except that the temperature must be carefully controlled since the chlorine-aryl bond breaks at 680 °C.

This resonance-stabilized intermediate is transported to a room temperature deposition chamber where polymerization occurs under low pressure (1–100 mTorr) conditions.

Originally the precursor was just thermally cracked,[25] but suitable catalysts lower the pyrolysis temperature, resulting in less char residue and a better coating.

[26][27] By either method an atomic bromine free-radical is given off from each methyl end, which can be converted to hydrogen bromide HBr and removed from monomer flow.

Since the coating process takes place at ambient temperature in a mild vacuum, it can be applied even to temperature-sensitive objects such as dry biological specimens.

Parylene C and to a lesser extent AF-4, SF, HT (all the same polymer) are used for coating printed circuit boards (PCBs) and medical devices.

[35] However, unless the gold or oxide surface is carefully treated and the alkyl chain is long, these SAMs form disordered monolayers, which do not pack well.

This finding of parylenes as molecular layers is very powerful for industrial applications because of the robustness of the process and that the MLs are deposited at room temperature.