Penrose tiling

[9] He also described a reduction to 104 such prototiles; the latter did not appear in his published monograph,[10] but in 1968, Donald Knuth detailed a modification of Berger's set requiring only 92 dominoes.

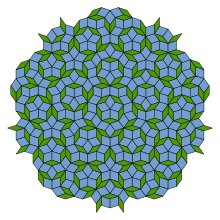

Any attempt to tile the plane with regular pentagons necessarily leaves gaps, but Johannes Kepler showed, in his 1619 work Harmonices Mundi, that these gaps can be filled using pentagrams (star polygons), decagons and related shapes.

[19] Acknowledging inspiration from Kepler, Penrose found matching rules for these shapes, obtaining an aperiodic set.

[22] Penrose and John H. Conway investigated the properties of Penrose tilings, and discovered that a substitution property explained their hierarchical nature; their findings were publicized by Martin Gardner in his January 1977 "Mathematical Games" column in Scientific American.

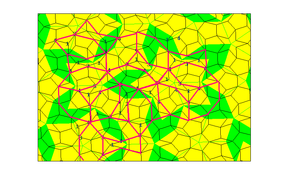

De Bruijn's "multigrid method" obtains the Penrose tilings as the dual graphs of arrangements of five families of parallel lines.

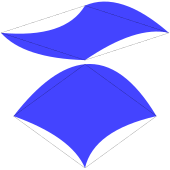

[29] Penrose's second tiling uses quadrilaterals called the "kite" and "dart", which may be combined to make a rhombus.

[21] These rules often force the placement of certain tiles: for example, the concave vertex of any dart is necessarily filled by two kites.

The corresponding figure (center of the top row in the lower image on the left) is called an "ace" by Conway; although it looks like an enlarged kite, it does not tile in the same way.

[33] Similarly the concave vertex formed when two kites meet along a short edge is necessarily filled by two darts (bottom right).

In fact, there are only seven possible ways for the tiles to meet at a vertex; two of these figures – namely, the "star" (top left) and the "sun" (top right) – have 5-fold dihedral symmetry (by rotations and reflections), while the remainder have a single axis of reflection (vertical in the image).

[34] Apart from the ace (top middle) and the sun, all of these vertex figures force the placement of additional tiles.

[35] The third tiling uses a pair of rhombuses (often referred to as "rhombs" in this context) with equal sides but different angles.

In one form, tiles must be assembled such that the curves on the faces match in color and position across an edge.

[36] The various combinations of angles and facial curvature allow construction of arbitrarily complex tiles, such as the Penrose chickens.

This shows that the Penrose tiling has a scaling self-similarity, and so can be thought of as a fractal, using the same process as the pentaflake.

[31] The smaller A-tile, denoted AS, is an obtuse Robinson triangle, while the larger A-tile, AL, is acute; in contrast, a smaller B-tile, denoted BS, is an acute Robinson triangle, while the larger B-tile, BL, is obtuse.

Furthermore, the matching rules also determine how the smaller triangles in the tiling compose to give larger ones.

For example, a tiling by kites and darts may be subdivided into A-tiles, and these can be composed in a canonical way to form B-tiles and hence rhombs.

In addition, the simple subdivision rule generates holes near the edges of the tiling which are just visible in the top and bottom illustrations on the right.

[33][45][46] The Penrose tilings, being non-periodic, have no translational symmetry – the pattern cannot be shifted to match itself over the entire plane.

However, any bounded region, no matter how large, will be repeated an infinite number of times within the tiling.

[49][51] The aperiodic nature of the coverings can make theoretical studies of physical properties, such as electronic structure, difficult due to the absence of Bloch's theorem.

It can be obtained either by decorating the rhombs of the original tiling with smaller ones, or by applying substitution rules, but not by de Bruijn's cut-and-project method.

The similarity with certain decorative patterns used in North Africa and the Middle East has been noted;[56][57] the physicists Peter J. Lu and Paul Steinhardt have presented evidence that a Penrose tiling underlies examples of medieval Islamic geometric patterns, such as the girih (strapwork) tilings at the Darb-e Imam shrine in Isfahan.

[58] Drop City artist Clark Richert used Penrose rhombs in artwork in 1970, derived by projecting the rhombic triacontahedron shadow onto a plane observing the embedded "fat" rhombi and "skinny" rhombi which tile together to produce the non-periodic tessellation.

Art historian Martin Kemp has observed that Albrecht Dürer sketched similar motifs of a rhombus tiling.

[59] In 1979, Miami University used a Penrose tiling executed in terrazzo to decorate the Bachelor Hall courtyard in their Department of Mathematics and Statistics.

[62] The Andrew Wiles Building, the location of the Mathematics Department at the University of Oxford as of October 2013,[63] includes a section of Penrose tiling as the paving of its entrance.

[64] The pedestrian part of the street Keskuskatu in central Helsinki is paved using a form of Penrose tiling.

[65] San Francisco's 2018 Salesforce Transit Center features perforations in its exterior's undulating white metal skin in the Penrose pattern.