Phase-contrast microscopy

Changes in amplitude (brightness) arise from the scattering and absorption of light, which is often wavelength-dependent and may give rise to colors.

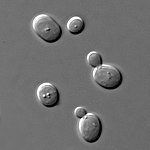

These structures were made visible to earlier microscopists by staining, but this required additional preparation and death of the cells.

When observing an unstained biological specimen, the scattered light is weak and typically phase-shifted by −90° (due to both the typical thickness of specimens and the refractive index difference between biological tissue and the surrounding medium) relative to the background light.

In a phase-contrast microscope, image contrast is increased in two ways: by generating constructive interference between scattered and background light rays in regions of the field of view that contain the specimen, and by reducing the amount of background light that reaches the image plane.

When the light is then focused on the image plane (where a camera or eyepiece is placed), this phase shift causes background and scattered light rays originating from regions of the field of view that contain the sample (i.e., the foreground) to constructively interfere, resulting in an increase in the brightness of these areas compared to regions that do not contain the sample.

Some of the scattered light that illuminates the entire surface of the filter will be phase-shifted and dimmed by the rings, but to a much lesser extent than the background light, which only illuminates the phase-shift and gray filter rings.

In 1952, Georges Nomarski patented what is today known as differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy.

[9] Traditional phase-contrast methods enhance contrast optically, blending brightness and phase information in a single image.