Phenotypic plasticity

[2] One mobile organism with substantial phenotypic plasticity is Acyrthosiphon pisum of the aphid family, which exhibits the ability to interchange between asexual and sexual reproduction, as well as growing wings between generations when plants become too populated.

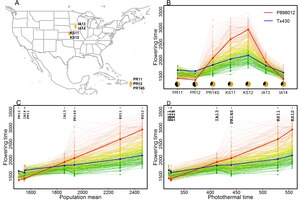

Identification of such explicit environment indices from critical growth periods being highly correlated with sorghum and rice flowering time enables such predictions.

[6][13] Additional work is being done to support the agricultural industry, which faces severe challenges in prediction of crop phenotypic expression in changing environments.

[16] Environmental factors, such as light and humidity, have been shown to affect leaf morphology,[17] giving rise to the question of how this shape change is controlled at the molecular level.

The Genetic Regulatory Network is responsible for creating this phenotypic plasticity and involves a variety of genes and proteins regulating leaf morphology.

[25] Plastic responses to temperature are essential among ectothermic organisms, as all aspects of their physiology are directly dependent on their thermal environment.

As such, thermal acclimation entails phenotypic adjustments that are found commonly across taxa, such as changes in the lipid composition of cell membranes.

Temperature change influences the fluidity of cell membranes by affecting the motion of the fatty acyl chains of glycerophospholipids.

[26] Phenotypic plasticity of the digestive system allows some animals to respond to changes in dietary nutrient composition,[27][28] diet quality,[29][30] and energy requirements.

Poor quality diets also result in lower concentrations of nutrients in the lumen of the intestine, which can cause a decrease in the activity of several digestive enzymes.

[30] Animals often consume more food during periods of high energy demand (e.g. lactation or cold exposure in endotherms), this is facilitated by an increase in digestive organ size and capacity, which is similar to the phenotype produced by poor quality diets.

The high copy number of AMY2B variants likely already existed as a standing variation in early domestic dogs, but expanded more recently with the development of large agriculturally based civilizations.

For example, water fleas (Daphnia magna), exposed to microsporidian parasites produce more offspring in the early stages of exposure to compensate for future loss of reproductive success.

[41] This particular form of plasticity has been shown in certain cases to be mediated by host-derived molecules (e.g. schistosomin in snails Lymnaea stagnalis infected with trematodes Trichobilharzia ocellata) that interfere with the action of reproductive hormones on their target organs.

[47] For example, birds that engage in altitudinal migration might make "trial runs" lasting a few hours that would induce physiological changes that would improve their ability to function at high altitude.

[47] Woolly bear caterpillars (Grammia incorrupta) infected with tachinid flies increase their survival by ingesting plants containing toxins known as pyrrolizidine alkaloids.

In a controlled experiment conducted by Karen Warkentin, hatching rate and ages of red-eyed tree frogs were observed in clutches that were and were not attacked by the cat-eyed snake.

[49][50] If the optimal phenotype in a given environment changes with environmental conditions, then the ability of individuals to express different traits should be advantageous and thus selected for.

Therefore, these freshwater snails produce either an adaptive or maladaptive response to the environmental cue depending on whether predatory sunfish are present or not.

[55][56] Given the profound ecological importance of temperature and its predictable variability over large spatial and temporal scales, adaptation to thermal variation has been hypothesized to be a key mechanism dictating the capacity of organisms for phenotypic plasticity.

Termed the "climatic variability hypothesis", this idea has been supported by several studies of plastic capacity across latitude in both plants and animals.

[58][59] However, recent studies of Drosophila species have failed to detect a clear pattern of plasticity over latitudinal gradients, suggesting this hypothesis may not hold true across all taxa or for all traits.

[60] Some researchers propose that direct measures of environmental variability, using factors such as precipitation, are better predictors of phenotypic plasticity than latitude alone.

[68] This is thought to be particularly important for species with long generation times, as evolutionary responses via natural selection may not produce change fast enough to mitigate the effects of a warmer climate.

Food abundance showed a significant effect on the breeding date with individual females, indicating a high amount of phenotypic plasticity in this trait.