Phosphoribulokinase

[2] Therefore, PRK activity often determines the metabolic rate in organisms for which carbon fixation is key to survival.

The possibility that PRK might exist was first recognized by Weissbach et al. in 1954; for example, the group noted that carbon dioxide fixation in crude spinach extracts was enhanced by the addition of ATP.

As of 2018, only two crystal structures have been resolved for this class of enzymes in Rhodobacter sphaeroides and Methanospirillum hungatei, with the respective PDB accession codes 1A7J and 5B3F.In Rhodobacter sphaeroides, PRK (or RsPRK) exists as a homooctomer with protomers composed of seven-stranded mixed β-sheets, seven α-helices, and an auxiliary pair of anti-parallel β-strands.

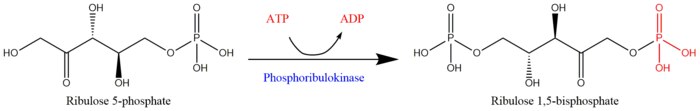

A catalytic residue in the enzyme (i.e. aspartate in RsPRK) deprotonates the O1 hydroxyl oxygen on RuP and activates it for nucleophilic attack of the γ-phosphoryl group of ATP.

[12] Some studies suggest that both substrates (ATP and RuP) bind simultaneously to PRK and form a ternary complex.

[13][14] In addition to binding its substrates, PRK also requires ligation to divalent metal cations like Mg2+ or Mn2+ for activity; Hg2+ has been demonstrated to inactivate the enzyme.

[15] However, at high concentrations, PRK may sometimes phosphorylate ribose 5-phosphate, a compound upstream the RuBP regeneration step in the Calvin Cycle.

Of such metabolites, 6-phosphogluconate has been shown to be the most effective inhibitor of eukaryotic PRK by competing with RuP for the enzyme's active site.

More recent work on the regulation of eukaryotic PRK has focused on its ability to form multi-enzyme complexes with other Calvin cycle enzymes such as glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) or RuBisCo.

For example, it has been shown that PRK-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase complexes in Scenedesmus obliquus only dissociate to release activated forms of its constituent enzymes in the presence of NADPH, dithiothreitol (DTT), and thioredoxin.