Phosphor

A phosphor is a substance that exhibits the phenomenon of luminescence; it emits light when exposed to some type of radiant energy.

Phosphors can be classified into two categories: fluorescent substances which emit the energy immediately and stop glowing when the exciting radiation is turned off, and phosphorescent substances which emit the energy after a delay, so they keep glowing after the radiation is turned off, decaying in brightness over a period of milliseconds to days.

Fluorescent materials are used in applications in which the phosphor is excited continuously: cathode-ray tubes (CRT) and plasma video display screens, fluoroscope screens, fluorescent lights, scintillation sensors, white LEDs, and luminous paints for black light art.

Phosphorus, the light-emitting chemical element for which phosphors are named, emits light due to chemiluminescence, not phosphorescence.

Those electrons and holes are captured successively by impurity centers exciting certain metastable states not accessible to the excitons.

In the case of inorganic scintillators, the activator impurities are typically chosen so that the emitted light is in the visible range or near-UV, where photomultipliers are effective.

In inorganic phosphors, these inhomogeneities in the crystal structure are created usually by addition of a trace amount of dopants, impurities called activators.

The host materials are typically oxides, nitrides and oxynitrides,[2] sulfides, selenides, halides or silicates of zinc, cadmium, manganese, aluminium, silicon, or various rare-earth metals.

In turn, other materials (such as nickel) can be used to quench the afterglow and shorten the decay part of the phosphor emission characteristics.

Many phosphor powders are produced in low-temperature processes, such as sol-gel, and usually require post-annealing at temperatures of ~1000 °C, which is undesirable for many applications.

Lamp manufacturers have changed compositions of phosphors to eliminate some toxic elements formerly used, such as beryllium, cadmium, or thallium.

The activators can undergo change of valence (usually oxidation), the crystal lattice degrades, atoms – often the activators – diffuse through the material, the surface undergoes chemical reactions with the environment with consequent loss of efficiency or buildup of a layer absorbing the exciting and/or radiated energy, etc.

The degradation of electroluminescent devices depends on frequency of driving current, the luminance level, and temperature; moisture impairs phosphor lifetime very noticeably as well.

White LED lamps consist of a blue or ultra-violet emitter with a phosphor coating that emits at longer wavelengths, giving a full spectrum of visible light.

For this, a phosphor coating is applied to a surface of interest and, usually, the decay time is the emission parameter that indicates temperature.

[citation needed] In these applications, the phosphor is directly added to the plastic used to mold the toys, or mixed with a binder for use as paints.

Between 1913 and 1950 radium-228 and radium-226 were used to activate a phosphor made of silver doped zinc sulfide (ZnS:Ag), which gave a greenish glow.

Furthermore, zinc sulfide undergoes degradation of its crystal lattice structure, leading to gradual loss of brightness significantly faster than the depletion of radium.

ZnS:Ag coated spinthariscope screens were used by Ernest Rutherford in his experiments discovering atomic nucleus.

Copper doped zinc sulfide (ZnS:Cu) is the most common phosphor used and yields blue-green light.

Copper and magnesium doped zinc sulfide (ZnS:Cu,Mg) yields yellow-orange light.

Current electroluminescent light sources tend to degrade with use, resulting in their relatively short operation lifetimes.

ZnS:Cu was the first formulation successfully displaying electroluminescence, tested at 1936 by Georges Destriau in Madame Marie Curie laboratories in Paris.

It has a great potential as a green down-conversion phosphor for white LEDs; a yellow variant also exists (α-SiAlON[22]).

Some newer white LEDs use a yellow and blue emitter in series, to approximate white; this technology is used in some Motorola phones such as the Blackberry as well as LED lighting and the original-version stacked emitters by using GaN on SiC on InGaP but was later found to fracture at higher drive currents.

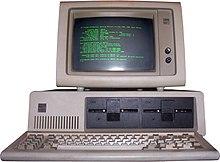

In the late 20th century, advanced electronics made new wide-deflection, "short tube" CRT technology viable, making CRTs more compact, but still bulky and heavy.

CRTs have also been widely used in scientific and engineering instrumentation, such as oscilloscopes, usually with a single phosphor color, typically green.

The screens are typically covered with phosphor using sedimentation coating, where particles suspended in a solution are let to settle on the surface.

The green phosphor initially used manganese-doped zinc silicate, then evolved through silver-activated cadmium-zinc sulfide, to lower-cadmium copper-aluminium activated formula, and then to cadmium-free version of the same.

LaOBr:Tb3+ is bright but water-sensitive, degradation-prone, and the plate-like morphology of its crystals hampers its use; these problems are solved now, so it is gaining use due to its higher linearity.