Pilus

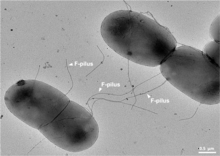

Some bacteria, viruses or bacteriophages attach to receptors on pili at the start of their reproductive cycle.

As the primary antigenic determinants, virulence factors and impunity factors on the cell surface of a number of species of gram-negative and some gram-positive bacteria, including Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonadaceae, and Neisseriaceae, there has been much interest in the study of pili as an organelle of adhesion and as a vaccine component.

They are sometimes called "sex pili", in analogy to sexual reproduction, because they allow for the exchange of genes via the formation of "mating pairs".

During conjugation, a pilus emerging from the donor bacterium ensnares the recipient bacterium, draws it in close, and eventually triggers the formation of a mating bridge, which establishes direct contact and the formation of a controlled pore that allows transfer of DNA from the donor to the recipient.

It has been suggested that in these archaea the conjugation machinery has been fully domesticated for promoting DNA repair through homologous recombination rather than spread of mobile genetic elements.

Fimbriae possess adhesins which attach them to some sort of substratum so that the bacteria can withstand shear forces and obtain nutrients.

This layer, called a pellicle, consists of many aerobic bacteria that adhere to the surface by their fimbriae.

Thus, fimbriae allow the aerobic bacteria to remain both on the broth, from which they take nutrients, and near the air.

Fimbriae are required for the formation of biofilm, as they attach bacteria to host surfaces for colonization during infection.

[14] The external ends of the pili adhere to a solid substrate, either the surface to which the bacterium is attached or to other bacteria.

Besides archaella, many archaea produce adhesive type 4 pili, which enable archaeal cells to adhere to different substrates.

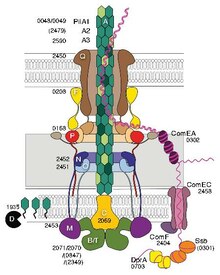

[17] Menningococcal type IV pili bind DNA through the minor pilin ComP via an electropositive stripe that is predicted to be exposed on the filament's surface.

[20] It has been shown that some archaeal type IV pilins can exist in 4 different conformations, yielding two pili with dramatically different structures.

[26] Some of the genes involved are CsgA, CsgB, CsgC, CsgD, CsgE, CsgF, and CsgG.

Fimbriae are one of the primary mechanisms of virulence for E. coli, Bordetella pertussis, Staphylococcus and Streptococcus bacteria.

[31] Nonpathogenic strains of V. cholerae first evolved pili, allowing them to bind to human tissues and form microcolonies.