Placebo

[4] Placebos in clinical trials should ideally be indistinguishable from so-called verum treatments under investigation, except for the latter's particular hypothesized medicinal effect.

Modern studies find that placebos can affect some outcomes such as pain and nausea, but otherwise do not generally have important clinical effects.

[9] Improvements that patients experience after being treated with a placebo can also be due to unrelated factors, such as regression to the mean (a statistical effect where an unusually high or low measurement is likely to be followed by a less extreme one).

[10] The use of placebos in clinical medicine raises ethical concerns, especially if they are disguised as an active treatment, as this introduces dishonesty into the doctor–patient relationship and bypasses informed consent.

They can affect how patients perceive their condition and encourage the body's chemical processes for relieving pain[10] and a few other symptoms,[12] but have no impact on the disease itself.

[13][14][15] From that, a singer of placebo became associated with someone who falsely claimed a connection to the deceased to get a share of the funeral meal, and hence a flatterer, and so a deceptive act to please.

[4] The placebo response may include improvements due to natural healing, declines due to natural disease progression, the tendency for people who were temporarily feeling either better or worse than usual to return to their average situations (regression toward the mean), and errors in the clinical trial records, which can make it appear that a change has happened when nothing has changed.

[22] Another Cochrane review in 2010 suggested that placebo effects are apparent only in subjective, continuous measures, and in the treatment of pain and related conditions.

The authors, Asbjørn Hróbjartsson and Peter C. Gøtzsche, concluded that their study "did not find that placebo interventions have important clinical effects in general".

[23][24][25][26][27] For example, recent research has linked placebo interventions to improved motor functions in patients with Parkinson's disease.

[12][28][29] Other objective outcomes affected by placebos include immune and endocrine parameters,[30][31] end-organ functions regulated by the autonomic nervous system,[32] and sport performance.

[38] A review published in JAMA Psychiatry found that, in trials of antipsychotic medications, the change in response to receiving a placebo had increased significantly between 1960 and 2013.

[44] An updated 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis based on 11 studies also found a significant, albeit slightly smaller overall effect of open-label placebos, while noting that "research on OLPs is still in its infancy".

In 2008, a meta-analysis led by psychologist Irving Kirsch, analyzing data from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), concluded that 82% of the response to antidepressants was accounted for by placebos.

[48] A complete reanalysis and recalculation based on the same FDA data found that the Kirsch study had "important flaws in the calculations".

[49] The authors concluded that although a large percentage of the placebo response was due to expectancy, this was not true for the active drug.

Informed consent is usually required for a study to be considered ethical, including the disclosure that some test subjects will receive placebo treatments.

[69] Edzard Ernst has argued similarly that "As a good doctor you should be able to transmit a placebo effect through the compassion you show your patients.

"[70] In an opinion piece about homeopathy, Ernst argues that it is wrong to support alternative medicine on the basis that it can make patients feel better through the placebo effect.

From a sociocognitive perspective, intentional placebo response is attributed to the “ritual effect” that induces anticipation for transition to a better state.

[citation needed] Functional imaging upon placebo analgesia suggests links to the activation, and increased functional correlation between this activation, in the anterior cingulate, prefrontal, orbitofrontal and insular cortices, nucleus accumbens, amygdala, the brainstem's periaqueductal gray matter,[82][83] and the spinal cord.

[87] Such analgesic placebos activation changes processing lower down in the brain by enhancing the descending inhibition through the periaqueductal gray on spinal nociceptive reflexes, while the expectations of anti-analgesic nocebos acts in the opposite way to block this.

[91] Pacheco-López and colleagues have raised the possibility of "neocortical-sympathetic-immune axis providing neuroanatomical substrates that might explain the link between placebo/conditioned and placebo/expectation responses".

[31]: 441 There has also been research aiming to understand underlying neurobiological mechanisms of action in pain relief, immunosuppression, Parkinson's disease and depression.

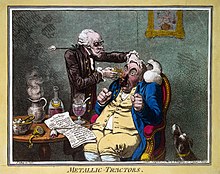

[96] It was recognized in the 18th and 19th centuries that drugs or remedies often were perceived to work best while they were still novel:[97] We know that, in Paris, fashion imposes its dictates on medicine just as it does with everything else.

[102] Clinical trials are often double-blinded so that the researchers also do not know which test subjects are receiving the active or placebo treatment.

The placebo effect in such clinical trials is weaker than in normal therapy since the subjects are not sure whether the treatment they are receiving is active.