Platonic solid

In geometry, a Platonic solid is a convex, regular polyhedron in three-dimensional Euclidean space.

[1] They are named for the ancient Greek philosopher Plato, who hypothesized in one of his dialogues, the Timaeus, that the classical elements were made of these regular solids.

Other evidence suggests that he may have only been familiar with the tetrahedron, cube, and dodecahedron and that the discovery of the octahedron and icosahedron belong to Theaetetus, a contemporary of Plato.

In any case, Theaetetus gave a mathematical description of all five and may have been responsible for the first known proof that no other convex regular polyhedra exist.

Of the fifth Platonic solid, the dodecahedron, Plato obscurely remarked, "...the god used [it] for arranging the constellations on the whole heaven".

Propositions 13–17 in Book XIII describe the construction of the tetrahedron, octahedron, cube, icosahedron, and dodecahedron in that order.

For each solid Euclid finds the ratio of the diameter of the circumscribed sphere to the edge length.

Andreas Speiser has advocated the view that the construction of the five regular solids is the chief goal of the deductive system canonized in the Elements.

In the 16th century, the German astronomer Johannes Kepler attempted to relate the five extraterrestrial planets known at that time to the five Platonic solids.

In Mysterium Cosmographicum, published in 1596, Kepler proposed a model of the Solar System in which the five solids were set inside one another and separated by a series of inscribed and circumscribed spheres.

Kepler proposed that the distance relationships between the six planets known at that time could be understood in terms of the five Platonic solids enclosed within a sphere that represented the orbit of Saturn.

The six spheres each corresponded to one of the planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn).

All other combinatorial information about these solids, such as total number of vertices (V), edges (E), and faces (F), can be determined from p and q.

The following geometric argument is very similar to the one given by Euclid in the Elements: A purely topological proof can be made using only combinatorial information about the solids.

The quantity h (called the Coxeter number) is 4, 6, 6, 10, and 10 for the tetrahedron, cube, octahedron, dodecahedron, and icosahedron respectively.

The icosahedron has the largest number of faces and the largest dihedral angle, it hugs its inscribed sphere the most tightly, and its surface area to volume ratio is closest to that of a sphere of the same size (i.e. either the same surface area or the same volume).

The dodecahedron, on the other hand, has the smallest angular defect, the largest vertex solid angle, and it fills out its circumscribed sphere the most.

Most importantly, the vertices of each solid are all equivalent under the action of the symmetry group, as are the edges and faces.

All Platonic solids except the tetrahedron are centrally symmetric, meaning they are preserved under reflection through the origin.

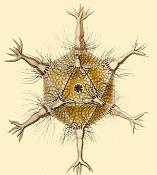

Examples include Circoporus octahedrus, Circogonia icosahedra, Lithocubus geometricus and Circorrhegma dodecahedra.

A regular polyhedron is used because it can be built from a single basic unit protein used over and over again; this saves space in the viral genome.

This has the advantage of evenly distributed spatial resolution without singularities (i.e. the poles) at the expense of somewhat greater numerical difficulty.

In the MERO system, Platonic solids are used for naming convention of various space frame configurations.

For the intermediate material phase called liquid crystals, the existence of such symmetries was first proposed in 1981 by H. Kleinert and K.

[13][14] In aluminum the icosahedral structure was discovered three years after this by Dan Shechtman, which earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2011.

Architects liked the idea of Plato's timeless forms that can be seen by the soul in the objects of the material world, but turned these shapes into more suitable for construction sphere, cylinder, cone, and square pyramid.

[15] In particular, one of the leaders of neoclassicism, Étienne-Louis Boullée, was preoccupied with the architects' version of "Platonic solids".

They form two of the thirteen Archimedean solids, which are the convex uniform polyhedra with polyhedral symmetry.

Spherical tilings provide two infinite additional sets of regular tilings, the hosohedra, {2,n} with 2 vertices at the poles, and lune faces, and the dual dihedra, {n,2} with 2 hemispherical faces and regularly spaced vertices on the equator.

In the mid-19th century the Swiss mathematician Ludwig Schläfli discovered the four-dimensional analogues of the Platonic solids, called convex regular 4-polytopes.