Political cartoon

They typically combine artistic skill, hyperbole and satire in order to either question authority or draw attention to corruption, political violence and other social ills.

[9][12] The medium began to develop in England in the latter part of the 18th century—especially around the time of the French Revolution—under the direction of its great exponents, James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson, both from London.

[4] Calling the king, prime ministers and generals to account, many of Gillray's satires were directed against George III, depicting him as a pretentious buffoon, while the bulk of his work was dedicated to ridiculing the ambitions of Revolutionary France and Napoleon.

Gillray's incomparable wit and humour, knowledge of life, fertility of resource, keen sense of the ludicrous, and beauty of execution, at once gave him the first place among caricaturists.

He gained notoriety with his political prints that attacked the royal family and leading politicians and was bribed in 1820 "not to caricature His Majesty" (George IV) "in any immoral situation".

[15] It was bought by Bradbury and Evans in 1842, who capitalised on newly evolving mass printing technologies to turn the magazine into a preeminent national institution.

Punch authors and artists also contributed to another Bradbury and Evans literary magazine called Once A Week (est.1859), created in response to Dickens' departure from Household Words.

[citation needed] The most prolific and influential cartoonist of the 1850s and 60s was John Tenniel, chief cartoon artist for Punch, who perfected the art of physical caricature and representation to a point that has changed little up to the present day.

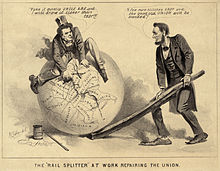

One of the most successful was Thomas Nast in New York City, who imported realistic German drawing techniques to major political issues in the era of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

American art historian Albert Boime argues that: As a political cartoonist, Thomas Nast wielded more influence than any other artist of the 19th century.

Both Lincoln and Grant acknowledged his effectiveness in their behalf, and as a crusading civil reformer he helped destroy the corrupt Tweed Ring that swindled New York City of millions of dollars.

Most cartoonists use visual metaphors and caricatures to address complicated political situations, and thus sum up a current event with a humorous or emotional picture.

"[19] Modern political cartooning can be built around traditional visual metaphors and symbols such as Uncle Sam, the Democratic donkey and the Republican elephant.

Thomas claimed defamation in the form of cartoons and words depicting the events of "Black Friday"—when he allegedly betrayed the locked-out Miners' Federation.