Statics

Statics is the branch of classical mechanics that is concerned with the analysis of force and torque acting on a physical system that does not experience an acceleration, but rather is in equilibrium with its environment.

The application of the assumption of zero acceleration to the summation of moments acting on the system leads to

(the 'second condition for equilibrium') can be used to solve for unknown quantities acting on the system.

[1][2] Later developments in the field of statics are found in works of Thebit.

A force is either a push or a pull, and it tends to move a body in the direction of its action.

Thus, force is a vector quantity, because its effect depends on the direction as well as on the magnitude of the action.

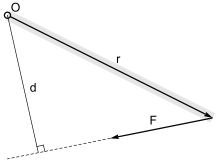

The magnitude of the moment of a force at a point O, is equal to the perpendicular distance from O to the line of action of F, multiplied by the magnitude of the force: M = F · d, where The direction of the moment is given by the right hand rule, where counter clockwise (CCW) is out of the page, and clockwise (CW) is into the page.

An engineering application of this concept is determining the tensions of up to three cables under load, for example the forces exerted on each cable of a hoist lifting an object or of guy wires restraining a hot air balloon to the ground.

While a simple scalar treatment of the moment of inertia suffices for many situations, a more advanced tensor treatment allows the analysis of such complicated systems as spinning tops and gyroscopic motion.

The concept was introduced by Leonhard Euler in his 1765 book Theoria motus corporum solidorum seu rigidorum; he discussed the moment of inertia and many related concepts, such as the principal axis of inertia.

Strength of materials is a related field of mechanics that relies heavily on the application of static equilibrium.

The position of the point relative to the foundations on which a body lies determines its stability in response to external forces.

If the center of gravity coincides with the foundations, then the body is said to be metastable.

Archimedes, Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī, Al-Khazini[8] and Galileo Galilei were also major figures in the development of hydrostatics.

"Using a whole body of mathematical methods (not only those inherited from the antique theory of ratios and infinitesimal techniques, but also the methods of the contemporary algebra and fine calculation techniques), Arabic scientists raised statics to a new, higher level.

The classical results of Archimedes in the theory of the centre of gravity were generalized and applied to three-dimensional bodies, the theory of ponderable lever was founded and the 'science of gravity' was created and later further developed in medieval Europe.

The combination of the dynamic approach with Archimedean hydrostatics gave birth to a direction in science which may be called medieval hydrodynamics.

[...] Numerous experimental methods were developed for determining the specific weight, which were based, in particular, on the theory of balances and weighing.

The classical works of al-Biruni and al-Khazini may be considered the beginning of the application of experimental methods in medieval science."