Hagen–Poiseuille equation

For velocities and pipe diameters above a threshold, actual fluid flow is not laminar but turbulent, leading to larger pressure drops than calculated by the Hagen–Poiseuille equation.

Another example is when blood flows into a narrower constriction, its speed will be greater than in a larger diameter (due to continuity of volumetric flow rate), and its pressure will be lower than in a larger diameter[4] (due to Bernoulli's equation).

However, the viscosity of blood will cause additional pressure drop along the direction of flow, which is proportional to length traveled[4] (as per Poiseuille's law).

In standard fluid-kinetics notation:[5][6][7] where The equation does not hold close to the pipe entrance.

[8]: 3 The equation fails in the limit of low viscosity, wide and/or short pipe.

Low viscosity or a wide pipe may result in turbulent flow, making it necessary to use more complex models, such as the Darcy–Weisbach equation.

The ratio of length to radius of a pipe should be greater than 1/48 of the Reynolds number for the Hagen–Poiseuille law to be valid.

In both cases, laminar or turbulent, the pressure drop is related to the stress at the wall, which determines the so-called friction factor.

The wall stress can be determined phenomenologically by the Darcy–Weisbach equation in the field of hydraulics, given a relationship for the friction factor in terms of the Reynolds number.

The theoretical derivation of a slightly different form of the law was made independently by Wiedman in 1856 and Neumann and E. Hagenbach in 1858 (1859, 1860).

[10] Poiseuille's law was later in 1891 extended to turbulent flow by L. R. Wilberforce, based on Hagenbach's work.

The radial momentum equation reduces to ∂p/∂r = 0, i.e., the pressure p is a function of the axial coordinate x only.

The axial momentum equation reduces to where μ is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid.

The average velocity can be obtained by integrating over the pipe cross section, The easily measurable quantity in experiments is the volumetric flow rate Q = πR2 uavg.

This force is proportional to the area of contact A, the velocity gradient perpendicular to the direction of flow Δvx/Δy, and a proportionality constant (viscosity) and is given by The negative sign is in there because we are concerned with the faster moving liquid (top in figure), which is being slowed by the slower liquid (bottom in figure).

Assume that we are figuring out the force on the lamina with radius r. From the equation above, we need to know the area of contact and the velocity gradient.

We don't know the exact form for the velocity of the liquid within the tube yet, but we do know (from our assumption above) that it is dependent on the radius.

That intersection is at a radius of r. So, considering that this force will be positive with respect to the movement of the liquid (but the derivative of the velocity is negative), the final form of the equation becomes where the vertical bar and subscript r following the derivative indicates that it should be taken at a radius of r. Next let's find the force of drag from the slower lamina.

To find the solution for the flow of a laminar layer through a tube, we need to make one last assumption.

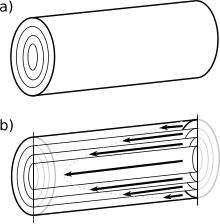

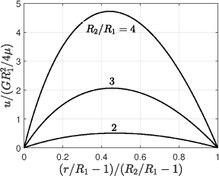

The Navier–Stokes equations reduce to with no-slip condition on both walls Therefore, the velocity distribution and the volume flow rate per unit length are Joseph Boussinesq derived the velocity profile and volume flow rate in 1868 for rectangular channel and tubes of equilateral triangular cross-section and for elliptical cross-section.

For an ideal gas in the isothermal case, where the temperature of the fluid is permitted to equilibrate with its surroundings, an approximate relation for the pressure drop can be derived.

Since the net force acting on the fluid is equal to ΔF = SΔp, where S = πr2, i.e. ΔF = πr2 ΔP, then from Poiseuille's law, it follows that For electrical circuits, let n be the concentration of free charged particles (in m−3) and let q* be the charge of each particle (in coulombs).

The Hagen–Poiseuille equation is useful in determining the vascular resistance and hence flow rate of intravenous (IV) fluids that may be achieved using various sizes of peripheral and central cannulas.

The equation states that flow rate is proportional to the radius to the fourth power, meaning that a small increase in the internal diameter of the cannula yields a significant increase in flow rate of IV fluids.