Polis

A collaborative study carried by the Copenhagen Polis Centre from 1993 to 2003 classified about 1,500 settlements of the Archaic and Classical ancient-Greek-speaking population as poleis.

[5][h] The few hundred ancient Greek classical works on line at the Perseus Digital Library use the word thousands of times.

[8] The theoretical study of the polis extends as far back as the beginning of Greek literature, when the works of Homer and Hesiod in places attempt to portray an ideal state.

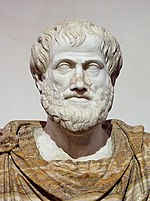

The study took a great leap forward when Plato and the academy in general undertook to define what is meant by the good, or ideal, polis.

According to Plato there are five main economic classes of any polis: producers, merchants, sailors/shipowners, retail traders and wage earners.

For example, Voegelin describes a model in which "town settlements" existed in the Aegean for a few thousand years prior to the Dorian invasions, forming an "aggregate, the pre-Doric city".

Only to read the title gives credibility to the idea that there is a model type inclusive of all ancient cities, and that the author need only present it without proving it.

Evander had led a colony from Arcadia before the Trojan War and had placed a polis (Livy's urbs) on one of the hills named Pallantium, later becoming Palatine.

When the band of marauders became populous enough Romulus got them to agree to a synoecism of settlements in the hills to form a new city, Rome, to be walled in immediately.

[17] The Germans had already invented the word in their own language: Stadtstaat, "city-state", referring to the many one-castle principates that abounded at the time.

"[18] He applied the word polis to it,[19] explaining that, "The Latin race, indeed, never realised the Greek conception ... but this was rather owing to their less vivid mental powers than to the absence of the phenomenon.

The rule of the city-state persisted until late in the 20th century, when the accumulation of mass data and sponsored databases made possible searches and comparisons of multiple sources not previously possible, a few of which are mentioned in this article.

The ancient writers referred to these initial moments under any of several words produced with the same prefix, sunoik- (Latinized synoec-), "same house", meaning objects that are from now on to be grouped together as being the same or similar.

A closely related meaning, "to colonize jointly with", is found there also, and in the whole gamut of historical writers, Xenophon, Plato, Strabo, Plutarch; i.e., more or less continuously through all periods from Archaic to Roman.

For example, Thucydides refers to Spartan lack of urbanity as "not synoecised", where synoecism is the creation of common living quarters (see above).

He uses the same word to describe the legal incorporation of the settlements around Athens into the city by King Theseus, although no special building was required.

It is generally agreed that the work is an accumulation of surviving treatises written at different times, and that the main logical break is the end of Book III.

Books I, II, and III, dubbed "Theory of the State" by Rackham in the Loeb Edition,[41] each represents an incomplete trial of the "Old Plan".

At the end of Book III, however, Aristotle encounters certain problems of definition that he cannot reconcile through theorization and has to abandon the sociology in favor of the New Plan, conclusions resulting from research on real constitutions.

In this sociological context politai can only be all the householders sharing in the polis, free or slave, male or female, child or adult.

The sum total of all the specific holdings mentioned in the treatise amount to the anthropological sense of property: land, animals, houses, wives, children, anything to which the right of access or disposition is reserved to the owner.

The ideal state therefore is impossible, a mere logical construct accounting for some of the factors, but failing of others, which Aristotle's examples suffice to demonstrate.

For survival the citizens of each city build a privately owned pool of diverse resources, which they can exchange for mutual ("reciprocal") benefit.

The presence of private property in the polis meant that it might be owned by foreigners (xenoi), raising questions of whether a single state existed there at all, or if it did, whose was it (III.I.12).

There are certain social activities that are generally agreed to be the concern of the whole community, such as justice and the redress of wrongs, public order, soldiering, and leadership of major events.

Its citizens on coming of age took an oath to uphold the law, according to Xenophon, usually as part of their mandatory military service.

Plato's Laws[51] speaks of politai (male) and politides (female) with reference to a recommendation that compulsory military training be applied to "not only the boys and men in the State, but also the girls and women....".

Invalidating the previous laws he cancelled the debts, starting with the large one owed him, made debt-slavery illegal, and set free the debt-slaves, going so far as to buy back Athenian citizens enslaved abroad.

After noting "there was a grey area between polis and civic subdivision, be it a demos or a kome or a phyle...",[55] Hansen remarks, "demos does not mean village but municipality, a territorial division of a people...."[56] The inventory of poleis published by the Copenhagen Study lists the type of civic subdivisions for each polis for which it could be ascertained (Index 13).

[57] Hansen suggests that these units, expressed generally in groups of komoi, were chosen because of their former role in synoecism, which also removed the former structures from service in favor of new municipalities.