Republic

This constitution was characterized by a Senate composed of wealthy aristocrats wielding significant influence; several popular assemblies of all free citizens, possessing the power to elect magistrates from the populace and pass laws; and a series of magistracies with varying types of civil and political authority.

In the late Middle Ages, writers such as Giovanni Villani described these states using terms such as libertas populi, a free people.

Philosophers and politicians advocating republics, such as Machiavelli, Montesquieu, Adams, and Madison, relied heavily on classical Greek and Roman sources which described various types of regimes.

[25] Modern scholars note the word democracy at the time of the 3rd century BC and later suffered from degradation and could mean any autonomous state, no matter how aristocratic in nature.

On the other hand, the Shakyas, Koliyas, Mallakas, and Licchavis,[clarification needed] during the period around Gautama Buddha, had the assembly open to all men, rich and poor.

It contains a chapter on how to deal with the saṅghas, which includes injunctions on manipulating the noble leaders, yet it does not mention how to influence the mass of the citizens, indicating that the gaṇasaṅgha are more of an aristocratic republic, than democracy.

[36] In Europe new republics appeared in the late Middle Ages when a number of small states embraced republican systems of government.

These were generally small, but wealthy, trading states, like the Mediterranean maritime republics and the Hanseatic League, in which the merchant class had risen to prominence.

Writers such as Bartholomew of Lucca, Brunetto Latini, Marsilius of Padua, and Leonardo Bruni saw the medieval city-states as heirs to the legacy of Greece and Rome.

Unlike Italy and Germany, much of the rural area was thus not controlled by feudal barons, but by independent farmers who also used communal forms of government.

In England James Harrington, Algernon Sidney, and John Milton became some of the first writers to argue for rejecting monarchy and embracing a republican form of government.

In addition, the widely distributed and popularly read-aloud tract Common Sense, by Thomas Paine, succinctly and eloquently laid out the case for republican ideals and independence to the larger public.

The majority of the population in most of Latin America was of either African or Amerindian descent, and the Creole elite had little interest in giving these groups power and broad-based popular sovereignty.

Simón Bolívar, both the main instigator of the revolts and one of its most important theorists, was sympathetic to liberal ideals but felt that Latin America lacked the social cohesion for such a system to function and advocated autocracy as necessary.

In East Asia, China had seen considerable anti-Qing sentiment during the 19th century, and a number of protest movements developed calling for constitutional monarchy.

The United States began to have considerable influence in East Asia in the later part of the 19th century, with Protestant missionaries playing a central role.

These combined with native Confucian inspired political philosophy that had long argued that the populace had the right to reject unjust governments that had lost the Mandate of Heaven.

The aftermath of World War II left Italy with a destroyed economy, a divided society, and anger against the monarchy for its endorsement of the Fascist regime.

[50] King Umberto II was pressured to call the 1946 Italian institutional referendum to decide whether Italy should remain a monarchy or become a republic.

[51] The supporters of the republic chose the effigy of the Italia turrita, the national personification of Italy, as their unitary symbol to be used in the electoral campaign and on the referendum ballot on the institutional form of the State, in contrast to the Savoy coat of arms, which represented the monarchy.

The United Kingdom attempted to follow the model it had for its earlier settler colonies of creating independent Commonwealth realms still linked under the same monarch.

While most of the settler colonies and the smaller states in the Caribbean and the Pacific retained this system, it was rejected by the newly independent countries in Africa and Asia, which revised their constitutions and became republics instead.

Britain followed a different model in the Middle East; it installed local monarchies in several colonies and mandates including Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Bahrain, Oman, Yemen and Libya.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the communists gradually gained control of Romania, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Hungary and Albania, ensuring that the states were reestablished as socialist republics rather than monarchies.

In other states the legislature is dominant and the presidential role is almost purely ceremonial and apolitical, such as in Germany, Italy, India, and Trinidad and Tobago.

The Roman Republic had two consuls, elected for a one-year term by the comitia centuriata, consisting of all adult, freeborn males who could prove citizenship.

The proponents of this system looked to classical examples, and the writings of the Italian Renaissance, and called their elective monarchy a rzeczpospolita, based on res publica.

French philosopher Jean Bodin's definition of the republic was "the rightly ordered government of a number of families, and of those things which are their common concern, by a sovereign power."

This ideology is based on the Roman Republic and the city states of Ancient Greece and focuses on ideals such as civic virtue, rule of law and mixed government.

[71] This understanding of a republic as a form of government distinct from a liberal democracy is one of the main theses of the Cambridge School of historical analysis.

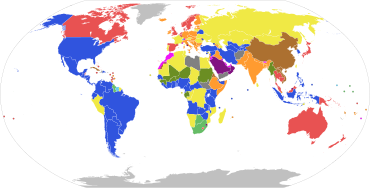

Parliamentary systems : Head of government is elected or nominated by and accountable to the legislature

Presidential system : Head of government (president) is popularly elected and independent of the legislature

Hybrid systems:

Other systems:

Note: this chart represents the de jure systems of government, not the de facto degree of democracy.