Political eras of the United States

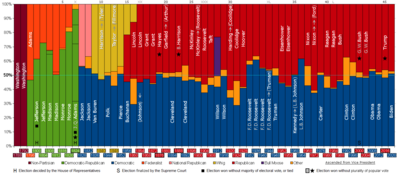

[2] Generally, the political history of America can be divided into eras of political hegemonic control of the federal government through unified control of the Presidency and the Congress’ House and Senate (when those houses of Congress are in session), hegemonic eras which can be further divided into seven party systems which each follow a realignment of voting blocs.

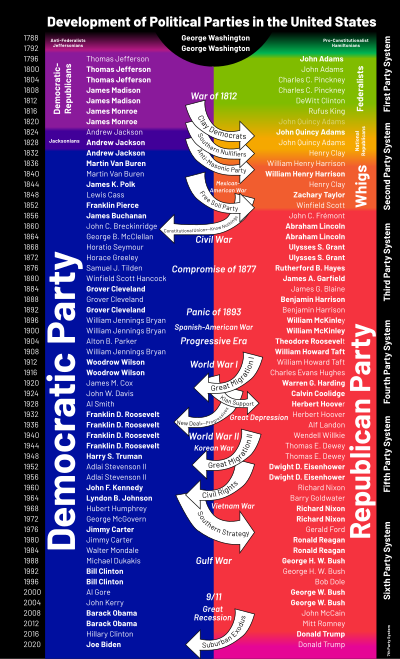

The hegemonic eras, defined by five periods in which a party's unified governments (including unified governments that occur because one or both of Congress’ two Houses are out of session) or divided governments occur for a continuous majority of time, and also happens to occur predominantly, are: The political significance of these five defined eras can be reinforced by the feature of each era beginning with near-unanimous Electoral College presidential victories that occur alongside the election of a unified trifecta of House, Senate and President for the hegemonic party (or alongside the election of divided government in the fifth era): Using these hegemonic eras as a framework, the more detailed specifics of party realignments and the seven party systems they take place in are described in detail below: The "First Party System" began in the 1790s with the 1792 re-election of George Washington and the 1796 election of John Adams, and ended in the 1820s with the presidential elections of 1824 and of 1828, resulting in Andrew Jackson's presidency.

Although distasteful to the participants, by the time John Adams and Thomas Jefferson ran for president in 1796, partisanship in the United States came to being.

[citation needed] With the decline in political consensus, it became imperative to revive Jeffersonian principles on the basis of Southern exceptionalism.

[19][20] It was in full swing with the 1828 United States presidential election, since the Federalists shrank to a few isolated strongholds and the Democratic-Republicans lost unity during the buildup to the American Civil War.

The opposition, leftover Federalist-aligned voters who formed the Clay and Adams factions in the Coastal North, realigned into the National Republican Party in 1828.

It was dominated by the new Republican Party, which claimed success in saving the Union, abolishing slavery and enfranchising the freedmen, while adopting many Whig-style modernization programs such as national banks, railroads, high tariffs, homesteads, social spending (such as on greater Civil War veteran pension funding), and aid to land grant colleges.

[23] The northern and western states were largely Republican, except for the closely balanced New York, Indiana, New Jersey, and Connecticut.

[24] Historians and political scientists generally believe that the Third Party System ended in the mid-1890s, which featured profound developments in issues of American nationalism, modernization, and race.

The central domestic issues concerned government regulation of railroads and large corporations ("trusts"), the money issue (gold versus silver), the protective tariff, the role of labor unions, child labor, the need for a new banking system, corruption in party politics, primary elections, the introduction of the federal income tax, direct election of senators, racial segregation, efficiency in government, women's suffrage, and control of immigration.

A few years after the Wall Street Crash of 1929, Herbert Hoover lost the 1932 United States presidential election to Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Key figures of the Fifth Party System include Franklin D. Roosevelt, the key founder of the New Deal coalition and president during most of the Great Depression and most of World War II; Harry S. Truman, successor to Franklin Roosevelt; John F. Kennedy; and civil rights champion Lyndon B. Johnson.

This allowed the party to gain dominant control of the Presidency after 1968 or 1980, though dominant control of Congress would remain in Democratic hands because of the Southern seats in Congress remaining a solid Democratic bloc until the Republicans flipped the Congressional South in the 1994 Republican Revolution.