Poll taxes in the United States

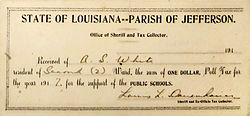

[4] Poll taxes had been a major source of government funding among the colonies which formed the United States.

[6] These laws, along with unfairly implemented literacy tests and extra-legal intimidation,[7] such as by the Ku Klux Klan, achieved the desired effect of disenfranchising Asian-American, Native American voters and poor whites as well, but in particular the poll tax was disproportionately directed at African-American voters.

Proof of payment of a poll tax was a prerequisite to voter registration in Florida, Alabama, Tennessee, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Georgia (1877), North and South Carolina, Virginia (until 1882 and again from 1902 with its new constitution),[8][9] and Texas (1902).

In 1942, an African American woman named Lottie Polk Gaffney, along with four other women, unsuccessfully sued the South Carolina Cherokee County Registration Board with the help of the NAACP.

In a kind of grandfather clause, North Carolina in 1900 exempted from the poll tax those men entitled to vote as of January 1, 1867.

[16] In 1937, in Breedlove v. Suttles, 302 U.S. 277 (1937), the United States Supreme Court found that poll tax as a prerequisite for registration to vote was constitutional.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 made clarifying remarks which helped to outlaw the practice nationwide, as well as make it enforceable by law.

In a two-month period in the spring of 1966, Federal courts declared unconstitutional poll tax laws in the last four states that still had them, starting with Texas on February 9.

Mississippi's $2.00 poll tax (equivalent to $19 in 2023) was the last to fall, declared unconstitutional on April 8, 1966, by a federal panel.

[20] Virginia attempted to partially abolish its poll tax by requiring a residence certification, but the Supreme Court rejected the arrangement in 1965 in Harman v. Forssenius.