Polyadenylation

The poly(A) tail consists of multiple adenosine monophosphates; in other words, it is a stretch of RNA that has only adenine bases.

[2] However, in a few cell types, mRNAs with short poly(A) tails are stored for later activation by re-polyadenylation in the cytosol.

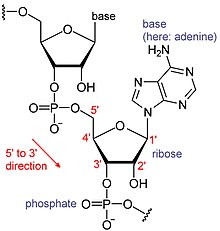

[7] RNAs are a type of large biological molecules, whose individual building blocks are called nucleotides.

[13] These are the only mRNAs in eukaryotes that lack a poly(A) tail, ending instead in a stem-loop structure followed by a purine-rich sequence, termed histone downstream element, that directs where the RNA is cut so that the 3′ end of the histone mRNA is formed.

There are small RNAs where the poly(A) tail is seen only in intermediary forms and not in the mature RNA as the ends are removed during processing, the notable ones being microRNAs.

[19] This site often has the polyadenylation signal sequence AAUAAA on the RNA, but variants of it that bind more weakly to CPSF exist.

[25][26] The polyadenylation signal – the sequence motif recognised by the RNA cleavage complex – varies between groups of eukaryotes.

[28] Through a poorly understood mechanism (as of 2002), it signals for RNA polymerase II to slip off of the transcript.

[32] Another protein, PAB2, binds to the new, short poly(A) tail and increases the affinity of polyadenylate polymerase for the RNA.

[45] This deadenylation and degradation process can be accelerated by microRNAs complementary to the 3′ untranslated region of an mRNA.

[46] In immature egg cells, mRNAs with shortened poly(A) tails are not degraded, but are instead stored and translationally inactive.

The level of access to the 5′ cap and poly(A) tail is important in controlling how soon the mRNA is degraded.

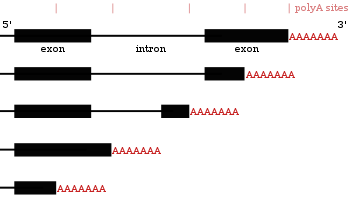

When more proximal (closer towards 5’ end) PAS sites are utilized, this shortens the length of the 3’ untranslated region (3' UTR) of a transcript.

[61] Ribo-sequencing data (sequencing of only mRNAs inside ribosomes) has shown that mRNA isoforms with shorter 3’ UTRs are more likely to be translated.

[27] The choice of poly(A) site can be influenced by extracellular stimuli and depends on the expression of the proteins that take part in polyadenylation.

This removes regulatory elements in the 3′ untranslated regions of mRNAs for defense-related products like lysozyme and TNF-α.

[74] In addition, numerous other components involved in transcription, splicing or other mechanisms regulating RNA biology can affect APA.

[75] For many non-coding RNAs, including tRNA, rRNA, snRNA, and snoRNA, polyadenylation is a way of marking the RNA for degradation, at least in yeast.

[76] This polyadenylation is done in the nucleus by the TRAMP complex, which maintains a tail that is around 4 nucleotides long to the 3′ end.

This poly(A) tail promotes degradation by the degradosome, which contains two RNA-degrading enzymes: polynucleotide phosphorylase and RNase E. Polynucleotide phosphorylase binds to the 3′ end of RNAs and the 3′ extension provided by the poly(A) tail allows it to bind to the RNAs whose secondary structure would otherwise block the 3′ end.

Successive rounds of polyadenylation and degradation of the 3′ end by polynucleotide phosphorylase allows the degradosome to overcome these secondary structures.

[82] In as different groups as animals and trypanosomes, the mitochondria contain both stabilising and destabilising poly(A) tails.

Like in bacteria, polyadenylation by polynucleotide phosphorylase promotes degradation of the RNA in plastids[89] and likely also archaea.

This enzyme is part of both the bacterial degradosome and the archaeal exosome,[93] two closely related complexes that recycle RNA into nucleotides.

[99] Poly(A)polymerase was first identified in 1960 as an enzymatic activity in extracts made from cell nuclei that could polymerise ATP, but not ADP, into polyadenine.

[100][101] Although identified in many types of cells, this activity had no known function until 1971, when poly(A) sequences were found in mRNAs.

[102][103] The only function of these sequences was thought at first to be protection of the 3′ end of the RNA from nucleases, but later the specific roles of polyadenylation in nuclear export and translation were identified.

The polymerases responsible for polyadenylation were first purified and characterized in the 1960s and 1970s, but the large number of accessory proteins that control this process were discovered only in the early 1990s.