Polynesia

The other land masses in Polynesia — New Zealand, Norfolk Island, and Ouvéa, the Polynesian outlier near New Caledonia — are the unsubmerged portions of the largely sunken continent of Zealandia.

However, they still cultivated other ancestral Austronesian staple cultigens like Dioscorea yams and taro (the latter are still grown with smaller-scale paddy field technology), as well as adopting new ones like breadfruit and sweet potato.

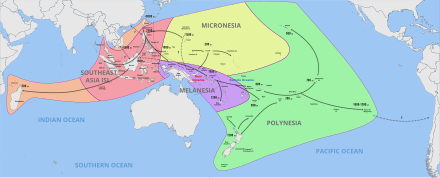

[26] Within a mere three or four centuries, between 1300 and 900 BC, the Lapita archaeological culture spread 6,000 km further to the east from the Bismarck Archipelago, until reaching as far as Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa.

Where there was once faint evidence of uniquely shared developments in Fijian and Polynesian speech, most of this is now called "borrowing" and is thought to have occurred in those and later years more than as a result of continuing unity of their earliest dialects on those far-flung lands.

[38][41] A genomic analysis of modern populations in Polynesia, published in 2021,[42] provides a model of the direction and timing of Polynesian migrations from Samoa to the islands to the east.

[43] The Polynesians were matrilineal and matrilocal Stone Age societies upon their arrival in Tonga, Samoa and the surrounding islands, after having spent at least some time in the Bismarck Archipelago.

The modern Polynesians still show human genetic results of a Melanesian culture which allowed indigenous men, but not women, to "marry in" – useful evidence for matrilocality.

[44] The Lapita pottery for which the general archaeological complex of the earliest "Oceanic" Austronesian speakers in the Pacific Islands are named also lapsed in Western Polynesia.

The first contact between Europeans and the native inhabitants of the Cook Islands took place in 1595 with the arrival of Spanish explorer Álvaro de Mendaña in Pukapuka, who called it San Bernardo (Saint Bernard).

A decade later, navigator Pedro Fernández de Quirós made the first European landing in the islands when he set foot on Rakahanga in 1606, calling it Gente Hermosa (Beautiful People).

The Lau Islands were subject to periods of Tongan rulership and then Fijian control until their eventual conquest by Seru Epenisa Cakobau of the Kingdom of Fiji by 1871.

Over the course of several centuries, the Polynesian settlers formed distinct cultures that became known as the Māori on the New Zealand mainland, while those who settled in the Chatham Islands became the Moriori people.

Traditional oral literature of Samoa and Manu'a talks of a widespread Polynesian network or confederacy (or "empire") that was prehistorically ruled by the successive Tui Manuʻa dynasties.

Oral history suggests that the Tui Manuʻa kings governed a confederacy of far-flung islands which included Fiji, Tonga as well as smaller western Pacific chiefdoms and Polynesian outliers such as Uvea, Futuna, Tokelau, and Tuvalu.

Commerce and exchange routes between the western Polynesian societies are well documented and it is speculated that the Tui Manuʻa dynasty grew through its success in obtaining control over the oceanic trade of currency goods such as finely woven ceremonial mats, whale ivory "tabua", obsidian and basalt tools, chiefly red feathers, and seashells reserved for royalty (such as polished nautilus and the egg cowry).

Samoa's long history of various ruling families continued until well after the decline of the Tui Manuʻa's power, with the western isles of Savaiʻi and Upolu rising to prominence in the post-Tongan occupation period and the establishment of the tafaʻifa system that dominated Samoan politics well into the 20th century.

The German-controlled Western portion of Samoa (consisting of the bulk of Samoan territory – Savaiʻi, Apolima, Manono and Upolu) was occupied by New Zealand in WWI, and administered by it under a Class C League of Nations mandate.

In 1875, with the help of the missionary Shirley Waldemar Baker, he declared Tonga a constitutional monarchy, formally adopted the western royal style, emancipated the "serfs", enshrined a code of law, land tenure, and freedom of the press, and limited the power of the chiefs.

The population levels of the low-lying islands of Tuvalu had to be managed because of the effects of periodic droughts and the risk of severe famine if the gardens were poisoned by salt from the storm surge of a tropical cyclone.

Remains of the plant in the Cook Islands have been radiocarbon-dated to 1000, and the present scholarly consensus[67] is that it was brought to central Polynesia c. 700 by Polynesians who had traveled to South America and back, from where it spread across the region.

[68] Some genetic evidence suggests that sweet potatoes may have reached Polynesia via seeds at least 100,000 years ago, pre-dating human arrival;[69] however, this hypothesis fails to account for the similarity of names.

[74][75][76] The anthropologist Wade Davis in his book The Wayfinders, criticized Heyerdahl as having "ignored the overwhelming body of linguistic, ethnographic, and ethnobotanical evidence, augmented today by genetic and archaeological data, indicating that he was patently wrong.

The pattern of settlement to East Polynesia began from Samoan Islands into the Tuvaluan atolls, with Tuvalu providing a stepping stone to migration into the Polynesian outlier communities in Melanesia and Micronesia.

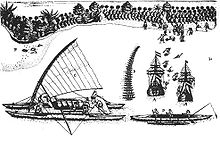

"[83] Religion, farming, fishing, weather prediction, out-rigger canoe (similar to modern catamarans) construction and navigation were highly developed skills because the population of an entire island depended on them.

"The rate of tourist growth has made the economy overly dependent on this one sector, leaving Hawaii extremely vulnerable to external economic forces.

"[87] By keeping this in mind, island states and nations similar to Hawaii are paying closer attention to other avenues that can positively affect their economy by practicing more independence and less emphasis on tourist entertainment.

The first major attempt at uniting the Polynesian islands was by Imperial Japan in the 1930s, when various theorists (chiefly Hachirō Arita) began promulgating the idea of what would soon become known as the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

The policy theorists who conceived it, along with the Japanese public, largely saw it as a pan-Asian movement driven by ideals of freedom and independence from Western colonial oppression.

In order to locate directions at various times of day and year, navigators in Eastern Polynesia memorized important facts: the motion of specific stars, and where they would rise on the horizon of the ocean; weather; times of travel; wildlife species (which congregate at particular positions); directions of swells on the ocean, and how the crew would feel their motion; colors of the sea and sky, especially how clouds would cluster at the locations of some islands; and angles for approaching harbors.

In contrast, sequences from two archaeological sites on Easter Island group with an uncommon haplogroup from Indonesia, Japan, and China and may represent a genetic signature of an early Polynesian dispersal.