Portraiture in ancient Egypt

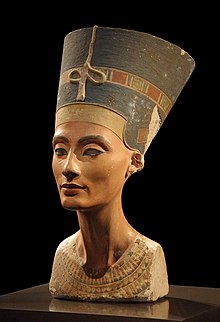

Portraiture in ancient Egypt forms a conceptual attempt to portray "the subject from its own perspective rather than the viewpoint of the artist ... to communicate essential information about the object itself".

[1] Ancient Egyptian art was a religious tool used "to maintain perfect order in the universe" and to substitute for the real thing or person through its representation.

Idealism apparent in ancient Egyptian art in general and specifically in portraiture was employed by choice, not as a result of lack of proficiency or talent.

Other factors contributing to the further clarification of the person's identity could include a certain facial expression, a physical action or pose, or presence of certain official regalia (for example, the scribal palette).

[5] Sometimes certain physical features reoccur in statues and reliefs of the same person, but that doesn't mean that they are portraits but rather a manifestation is a single quality or aspect.

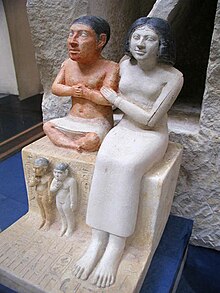

[11] In such funerary context, the deceased's statue was not just an abode for his personality, but also became the focal point of the cult's offerings; in other words, "the image became the reality".

The debate arises because of the expression of the inner qualities – that have no concrete manifestation – in contrast to the physical resemblance that is more emphasized for the easy identification of the subject.

Nevertheless, throughout history, the inner life was found to be more important because it is the main characteristic of an individual and continuous attempts are made to further express such a fleeting concept visually.

[13] Religious and funerary influence on ancient Egyptian art is great as is made it utilitarian rather than aesthetic mainly "commissioned for the tomb or the temple destined to be seen by only a few persons".

[14] Therefore, idealizing work is propagandistic to represent "the perfect human figure, the culmination of all that the Egyptians held to be good" as religion and fear of death and the afterlife were ruling forces over the Egyptians' minds and idealism is a means for them to achieve the desired happy ending as "it compromises a tangible affirmation of the individual's adherence to Ma'at and virtue as proclaimed in tomb biographies and chapter 125 of the Book of the Dead".

[14] Therefore, to achieve the expression of the "virtuous" person, the artist's perception and techniques of portrayal underwent "the process of selection, deletion and arrangement".

Old age is a sign of wisdom and hard work as in Senwosret III's case as well as wealth expressed through corpulence of the body.

The latter exhibit more variety of postures, costumes, activity and age as seen in scenes of working women, market places, and mothers and off springs.

It is sometimes distinguished (although the usage of both terms is highly variable) from realism, "which is the rendering of the qualities, (inner and outer), of a particular person"[20] However, both avoid the abstractive nature of idealism.

[23] Egyptian artists and artisans worked within a strict framework dictated by ethical, religious, social and magical considerations.

The statue or relief had to conform "to highly developed set of ethical principles and it was the artist's task to represent the model as a loyal adherent", but still considering the naturalizing tendencies evolving with time, it is possible to say that "something of both the physical and appearance and the personality of the individual was made manifest".

That was an imposed request from her for political reasons to legitimize her rule as a woman (that is considered a sign of decay and chaos) and to emphasize her adherence to Ma'at by ascertaining her male identity.

[6] Akhenaton's depiction is "the most extreme variation from the standard canon... showing the king with an elongated neck, drooping jaw, and fleshly feminine body".

If the judges of the afterlife are the intended audience, then the patron would want himself idealized as much as possible in order to adhere to Ma'at and to be capable of inhabiting a perfect and youthful body eternally.

However, if the audience were meant to be the masses, then the patron's political agenda would dictate the nature of the representation: the king would want himself portrayed in as powerful and as godlike a way as possible.