Problem of two emperors

This changed in 797 when Emperor Constantine VI was deposed, blinded, and replaced as ruler by his mother, Empress Irene, whose rule was ultimately not accepted in Western Europe, the most frequently cited reason being that she was a woman.

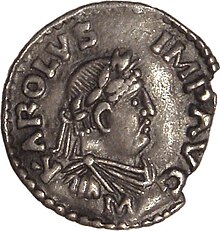

Rather than recognizing Irene, Pope Leo III proclaimed the king of the Franks, Charlemagne, as the emperor of the Romans in 800 under the concept of translatio imperii (transfer of imperial power).

At the same time, Charlemagne's courtier Alcuin had suggested that the imperial throne was now vacant since a woman claimed to be emperor, perceived as a symptom of the decadence of the empire in the east.

Liutprand recorded the outburst of Nikephoros's representatives at this letter, which illustrates that the Byzantines too had developed an idea similar to translatio imperii regarding the transfer of power from Rome to Constantinople:[22]Hear then!

Manuel aspired to lessen the influence of his two rivals and at the same time win the recognition of the Pope (and thus by extension Western Europe) as the sole legitimate emperor, which would unite Christendom under his sway.

Manuel reached for this ambitious goal by financing a league of Lombard towns to rebel against Frederick and encouraging dissident Norman barons to do the same against the Sicilian king.

[31] In his treaties and negotiations with Barbarossa (which exist preserved as written documents), Isaac II was insincere as he had secretly allied with Saladin to gain concessions in the Holy Land and had agreed to delay and destroy the German army.

On his way to the city of Niš, Barbarossa was repeatedly assaulted by locals under the orders of the governor of Branitchevo and Isaac II also engaged in a campaign of closing roads and destroying foragers.

[39] Frederick then continued on towards the Holy Land without any further major incidents with the Byzantines, with the exception of the German army almost sacking the city of Philadelphia after its governor refused to open up the markets to the Crusaders.

[41] Frederick Barbarossa died before reaching the Holy Land and his son and successor, Henry VI, pursued a foreign policy in which he aimed to force the Byzantine court to accept him as the superior (and sole legitimate) emperor.

His attempt to subordinate the Byzantine Empire to himself was just one step in his partially successful plan of extending his feudal overlordship from his own domains to France, England, Aragon, Cilician Armenia, Cyprus and the Holy Land.

[48] The threat of Henry VI caused some concern in the Byzantine Empire and Alexios III slightly altered his imperial title to en Christoi to theo pistos basileus theostephes anax krataios huspelos augoustos kai autokrator Romaion in Greek and in Christo Deo fidelis imperator divinitus coronatus sublimis potens excelsus semper augustus moderator Romanorum in Latin.

[57] Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II later formed an alliance with their rival, John III Doukas Vatatzes of the Nicene Empire against the Papal State which had been in conflict with.

[63] With the Byzantine reconquest of Constantinople in 1261 under Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos, the Papacy suffered a loss of prestige and endured severe damage to its spiritual authority.

[64] From 1266 to his death in 1282, Michael would repeatedly be threatened by the King of Sicily, Charles of Anjou, who aspired to restore the Latin Empire and periodically enjoyed Papal support.

[74] Following Michael's death, and with the threat of an Angevin invasion having subsided following the Sicilian Vespers, his successor, Andronikos II Palaiologos, was quick to repudiate the hated Union of the Churches.

[77] Although Michael VIII, unlike his predecessors, did not protest when addressed as the "Emperor of the Greeks" by the popes in letters and at the Council of Lyons, his conception of his universal emperorship remained unaffected.

The problem was solved when Simeon died in 927 and his son and successor, Peter I, simply adopted Emperor of the Bulgarians as a show of submission to the universal empire of Constantinople.

[96] In an inscription in the Holy Forty Martyrs Church following the Battle of Klokotnitsa, Ivan Asen II refers to Thessalonican emperor Theodore Komnenos Doukas as "tsar".

[99] In the 1230s, Nicene emperor John III Doukas Vatatzes forged an alliance with Ivan Asen II against the Latins by marrying his son Theodore to Elena.

In 1282, Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII proposed John II of Trebizond to use the title despot instead and cease using the imperial insignia in return for a marriage with his daughter Eudokia Palaiologina.

Such arrangement is seen as unlikely[126] and Frederick II rather addressed him as his equal avoiding the term vassal which he had been using for Italian lords and cities[127] but it is seen as probably that John III provided military help in exchange for his claims.

Mehmed deliberately linked himself to the Byzantine imperial tradition, making few changes in Constantinople itself and working on restoring the city through repairs and (sometimes forced) immigration, which soon led to an economic upswing.

[137] Emperor Charles VI considered using his potential claim to the Byzantine throne through Andreas Palaiologos's last will against the Ottomans but the expected success by Prince Eugene of Savoy did not came to fruition.

In the 1606 Peace of Zsitvatorok Ottoman sultan Ahmed I, for the first time in his empire's history, formally recognized the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II with the title császár (Hungarian for Ceasar) rather than kıral.

[150] According to Marshall Poe, the Third Rome theory first spread among clerics, and for much of its early history still regarded Moscow subordinate to Constantinople (Tsargrad), a position also held by Ivan IV.

An expansionist version of Third Rome reappeared primarily after the coronation of Alexander II in 1855, a lens through which later Russian writers would re-interpret Early Modern Russia, arguably anachronistically.

Under Peter, use of the double-headed eagle increased and other less Byzantine symbols of the Roman past were adopted, as when the tsar was portrayed as an ancient emperor on coins minted after the Battle of Poltava in 1709.

It was only in 1745 that the imperial electoral college acknowledged Russian claims, which were then confirmed in the document produced by the newly elected emperor Francis I (Maria Theresa's husband) and formally ratified by the Reichstag in 1746.

At the Council of Florence [it] in 1055, according to Mariana, the Emperor Henry III urged Pope Victor II to prohibit under severe penalties the use of the imperial title by Ferdinand.