Proclamation of the French Republic (September 4, 1870)

With the support of Empress Eugénie, the ultra-Bonapartist deputies, who were opposed to the liberal regime and the peace advocated by Émile Ollivier, pressured France to demand a written commitment of definitive renunciation and guarantees for the future from the King of Prussia.

Incidents were documented in Marseille, Toulon, Montpellier, Nîmes, Mâcon, Beaune, Limoges, Bordeaux, and Périgueux,[10] while in Lyon, some groups considered seceding from the Empire and establishing municipal autonomy.

The emperor contemplated a strategic withdrawal to Paris, but under considerable pressure from the empress and the Minister of War, who feared such a decision would incite popular unrest,[6] Napoleon III ultimately opted to march to Bazaine's aid with the Army of Châlons, which was under the command of Marshal MacMahon.

[15] The potential of the Empress and a government delegation relocating to a provincial city was contemplated, yet ultimately dismissed due to concerns that it might be perceived as a betrayal by the people of Paris, particularly in light of the Prussian army's advancement towards the capital.

[15] Similarly, Eugène Schneider, president of the Legislative Body [fr], who was entitled to participate in the council with a consultative voice, used a recess in the session to propose to Eugénie that executive power be transferred to a commission elected by the deputies.

[15] In his essay, Pierre Cornut-Gentille [fr] posited that the Empress's indecision was a consequence of her inability to make decisions without first ascertaining the intentions of General Trochu, the military governor of Paris.

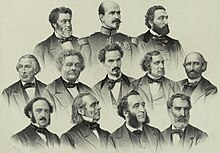

[19] Jules Favre then put forth the proposal of a triumvirate, comprising the President of the Legislative Body, Eugène Schneider; the Minister of War, Charles Cousin-Montauban; and the Governor of Paris, General Trochu.

A considerable number of individuals participated in a demonstration that commenced at Place de la Bastille and subsequently dispersed without incident at the hands of law enforcement personnel in the vicinity of Rue Montmartre.

In the early evening, crowds congregated at Place de la Concorde and the nearby bridge, anticipating that the Legislative Body [fr] would convene to declare the emperor's downfall.

[23] In light of the reports indicating the resolve of various groups congregated around the Palais Bourbon, it became imperative to convene the Legislative Body during the night to proclaim the transfer of executive authority to the Parisians at dawn.

[28][29] During the Council, the Minister of Agriculture and Commerce, Clément Duvernois [fr], was the first to propose the use of force, including the declaration of a state of siege, as a means of apprehending republican leaders and thereby quelling any revolutionary movements.

[34] While the majority of Parisians assembled in front of the palace were driven by concerns or a desire to observe the unfolding events, Blanquists and other revolutionaries mingled with the crowd, aiming to accelerate the collapse of the Empire and finally achieve the popular and egalitarian democracy that had failed in 1848.

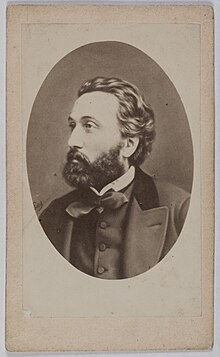

Rochefort, recently released from Sainte-Pélagie prison after serving a sentence of several months, was transported by his supporters to the City Hall, where he appeared wearing a red sash.

[47] In the absence of the requisite expertise to head the other ministries, Emmanuel Arago, Louis-Antoine Garnier-Pagès, Alexandre Glais-Bizoin, Eugène Pelletan, and Henri Rochefort are appointed ministers without portfolio but are permitted to participate in deliberations, thus enabling the new government to include individuals who are not deputies of Paris.

[47] Diameter: 4.6 cm, weight: 42.16 g. An extraordinary occurrence in the annals of the French Revolution, several municipalities situated in the heart of the country, as well as those located in the southern regions, witnessed the initial stages of the revolutionary upheaval before Paris.

[54] The population of Paris, facing unemployment, rising prices for essential goods, and later cold and famine in the heart of winter, demonstrates remarkable resilience but eventually succumbs to exhaustion, particularly as the Prussian army commenced bombardment of the capital on January 5, 1871.

Jules Favre initiated armistice negotiations, resulting in the signing of the convention on January 26, which revealed internal governmental tensions, as Gambetta opposed it and resigned on February 6.

From the perspective of the monarchist majority, whose objective is to discredit the Republic, the aim is to ascertain whether members of this government were complicit in a plot against the Legislative Body [fr] and thus became accomplices of the future Communards.

On August 31, 1871, Thiers's authority was further reinforced by the vote on the Rivet Act [fr], which formally conferred upon him the title of President of the Republic and extended his tenure until the establishment of the country's definitive institutions.

All signs recalling the Empire—the eagles, the coats of arms—were torn down and thrown into the water.The fervor of this revolutionary day causes the people to overlook the miseries of war and the threat posed by the Prussian invasion, as journalist and dramatic critic Francisque Sarcey states frankly in Le Siège de Paris, 1871.

[74] As Olivier Le Trocquer observed, the central question was whether the protagonists had erred, whether they were culpable or not in terms of public morality, or whether, conversely, gratitude should be extended to them for overthrowing the Empire and seizing power.

[74] For instance, in the initial volume of his Histoire contemporaine (1897), historian Samuel Denis was notably condemnatory, asserting that the men of September 4 were guilty of a manifest usurpation not sufficiently justified by the precarious circumstances.

[87] Jean-Pierre Azéma and Michel Winock also criticized the "iconic image" according to which that day, "the republic, like a phoenix rising from its ashes, imposed itself on France to save the homeland.

"[88] In 1973, Alain Plessis [fr], inspired by recent research on the Commune, identified it as the true breakpoint instead of 1870 and adopted the social aspect of the event while downplaying the revolutionary nature of September 4.

A cursory examination of the curricula of middle and high schools, as well as the content of university courses, reveals that these twenty-three years occupy a negligible portion of the educational landscape.

This observation led Olivier Le Trocquer to suggest that "for contemporaries, these rites marked the revolutionary nature of the event, and their later erasure accompanied the euphemized reinterpretation of September 4.

[34] When Jules Favre and Léon Gambetta led the procession towards the Hôtel de Ville to proclaim the Republic, they sought to preempt the far-left leaders who could have exploited the circumstances to overthrow the social order.

[105] Never celebrated, never commemorated, September 4, 1870, seems today erased from national memory.As early as 1930, historian Daniel Halévy employed the term "obscure times" to characterize the nascent period of the Third Republic.

In 1970, the centenary of the Third Republic was commemorated with a colloquium on the Republican spirit, organized by the University of Orléans, and an exhibition at the Hôtel de Ville in Paris, inaugurated by President Georges Pompidou.

As Olivier Le Trocquer observed, the speech gave rise to a significant political question: whether the legitimacy of public salvation, as embodied by the Republic, should prevail over existing legality in times of crisis.