Proper velocity

For example, proper velocity equals momentum per unit mass at any speed, and therefore has no upper limit.

[2] Fraundorf has explored its pedagogical value[3] while Ungar,[4] Baylis[5] and Hestenes[6] have examined its relevance from group theory and geometric algebra perspectives.

Imagine an object traveling through a region of spacetime locally described by Hermann Minkowski's flat-space metric equation (cdτ)2 = (cdt)2 − (dx)2.

Thus finite w ensures that v is less than lightspeed c. By grouping γ with v in the expression for relativistic momentum p, proper velocity also extends the Newtonian form of momentum as mass times velocity to high speeds without a need for relativistic mass.

In the unidirectional case this becomes commutative and simplifies to a Lorentz factor product times a coordinate velocity sum, e.g. to wAC = γABγBC(vAB + vBC), as discussed in the application section below.

The table below illustrates how the proper velocity of w = c or "one map-lightyear per traveler-year" is a natural benchmark for the transition from sub-relativistic to super-relativistic motion.

The following equations convert between four alternate measures of speed (or unidirectional velocity) that flow from Minkowski's flat-space metric equation: or in terms of logarithms: Proper velocity is useful for comparing the speed of objects with momentum per unit rest mass (w) greater than lightspeed c. The coordinate speed of such objects is generally near lightspeed, whereas proper velocity indicates how rapidly they are covering ground on traveling-object clocks.

Hence each of two electrons (A and C) in a head-on collision at 45 GeV in the lab frame (B) would see the other coming toward them at vAC ~ c and wAC = 88,0002(1 + 1) ~ 1.55×1010 lightseconds per traveler second.

Thus from the target's point of view, colliders can explore collisions with much higher projectile energy and momentum per unit mass.

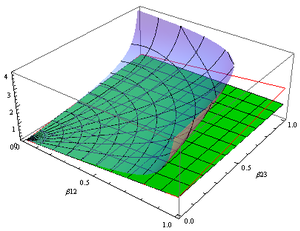

Such plots can for example be used to show where the speed of light, the Planck constant, and Boltzmann energy kT figure in.

Objects that fit nicely on this plot are humans driving cars, dust particles in Brownian motion, a spaceship in orbit around the Sun, molecules at room temperature, a fighter jet at Mach 3, one radio wave photon, a person moving at one lightyear per traveler year, the pulse of a 1.8 MegaJoule laser, a 250 GeV electron, and our observable universe with the blackbody kinetic energy expected of a single particle at 3 kelvin.

Not only may observers in all frames agree on its magnitude, but it also measures the extent to which an accelerating rocket "has its pedal to the metal".

In the unidirectional case i.e. when the object's acceleration is parallel or anti-parallel to its velocity in the spacetime slice of the observer, the change in proper velocity is the integral of proper acceleration over map time i.e. Δw = αΔt for constant α.

To be specific: where as noted above the various velocity parameters are related by These equations describe some consequences of accelerated travel at high speed.

For a map distance of ΔxAB, the first equation above predicts a midpoint Lorentz factor (up from its unit rest value) of γmid = 1 + α(ΔxAB/2)/c2.