Indo-Aryan migrations

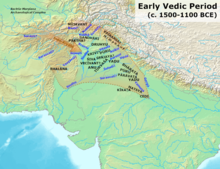

[3] Indo-Aryan migration into the region, from Central Asia, is considered to have started after 2000 BCE as a slow diffusion during the Late Harappan period and led to a language shift in the northern Indian subcontinent.

[11] The language-family and migration theory were further developed, in the 18th century, by Jesuit missionary Gaston-Laurent Coeurdoux, and later East India Company employee William Jones, in 1786,[12] through analysing similarities between European, West and South Asian languages.

[34][note 4] The Indo-Aryan migrations form part of a complex genetic puzzle on the origin and spread of the various components of the Indian population, including various waves of admixture and language shift.

[45] While Reich notes that the onset of admixture coincides with the arrival of Indo-European language,[web 2] according to Moorjani et al. (2013) these groups were present "unmixed" in India before the Indo-Aryan migrations.

A number of Indologists and historians offering the Baudhayana Shrauta Sutra, verse 18.44:397.9, as explicit recorded evidence of a migration:[59][60][61][62] Then, there is the following direct statement contained in (the admittedly much later) BSS [Baudhāyana Śrauta Sūtra] 18.44:397.9 sqq which has once again been overlooked, not having been translated yet: "Ayu went eastwards.

[83] The excavation of the Harappa, Mohenjo-daro and Lothal sites of the Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) in the 1920,[84] showed that northern India already had an advanced culture when the Indo-Aryans migrated into the area.

This argument was proposed by the mid-20th century archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler, who interpreted the presence of many unburied corpses found in the top levels of Mohenjo-daro as the victims of conquest wars, and who famously stated that the god "Indra stands accused" of the destruction of the Civilisation.

[citation needed] PIE is thought to have had a complex system of morphology that included inflectional suffixes as well as ablaut (vowel alterations, as preserved in English sing, sang, sung).

The strong correspondence between the dialectal relationships of the Indo-European languages and their actual geographical arrangement in their earliest attested forms makes an Indian origin, as suggested by the Out of India Theory, unlikely.

[113] About 6,000 years ago the Indo-Europeans started to spread out from their proto-Indo-European homeland in Central Eurasia, between the southern Ural Mountains, the North Caucasus, and the Black Sea.

The Proto-Indo-Iranians are commonly identified with the Andronovo culture,[112] that flourished c. 2000–1450 BCE in an area of the Eurasian Steppe that borders the Ural River on the west, the Tian Shan on the east.

[130] The earliest known chariots have been found in Sintashta burials, and the culture is considered a strong candidate for the origin of the technology, which spread throughout the Old World and played an important role in ancient warfare.

According to Bryant, the Bactria-Margiana material inventory of the Mehrgarh and Baluchistan burials is "evidence of an archaeological intrusion into the subcontinent from Central Asia during the commonly accepted time frame for the arrival of the Indo-Aryans".

[citation needed] At the height of its power, during the 14th century BCE, Mitanni had outposts centered on its capital, Washukanni, whose location has been determined by archaeologists to be on the headwaters of the Khabur River.

This shift by Harappan and, perhaps, other Indus Valley cultural mosaic groups, is the only archaeologically documented west-to-east movement of human populations in the Indian subcontinent before the first half of the first millennium B.C.

The Kushan empire stretched from Turpan in the Tarim Basin to Pataliputra on the Indo-Gangetic Plain at its greatest extent, and played an important role in the development of the Silk Road and the transmission of Buddhism to China.

Around the first millennium of the Common Era (AD), the Kambojas, the Pashtuns and the Baloch began to settle on the eastern edge of the Iranian Plateau, on the mountainous frontier of northwestern and western Pakistan, displacing the earlier Indo-Aryans from the area.

The Indo-Aryan migrations form part of a complex genetical puzzle on the origin and spread of the various components of the Indian population, including various waves of admixture and language shift.

[37][note 37] ArunKumar et al. (2015) "suggest that ancient male-mediated migratory events and settlement in various regional niches led to the present day scenario and peopling of India.

"[222] Mahl (2021), in a study of the Brahmin ethnic group, identified the ancient male protagonists of the sampled population could be traced to twelve geographic locations, eleven of which were outside South Asia.

"[227] Moorjani (2013) describes three scenarios regarding the bringing together of the two groups:[45] Metspalu et al. (2011) detected a genetic component in India, k5, which "distributed across the Indus Valley, Central Asia, and the Caucasus".

"[230] Speaking to Fountain Ink, Metspalu said, "the West Eurasian component in Indians appears to come from a population that diverged genetically from people actually living in Eurasia, and this separation happened at least 12,500 years ago.

9,300 ± 3,000 years before present,[244] which coincides with "the arrival to India of cereals domesticated in the fertile Crescent" and "lends credence to the suggested linguistic connection between Elamite and Dravidic populations".

[48] Silva et al. (2017) state that "the recently refined Y-chromosome tree strongly suggests that R1a is indeed a highly plausible marker for the long-contested Bronze Age spread of Indo-Aryan speakers into South Asia.

"[243] Ornella Semino et al. (2000) proposed Ukrainian origins of R1a1, and a postglacial spread of the R1a1 gene during the Late Glacial, subsequently magnified by the expansion of the Kurgan culture into Europe and eastward.

[267] Spencer Wells proposes central Asian origins, suggesting that the distribution and age of R1a1 points to an ancient migration corresponding to the spread by the Kurgan people in their expansion from the Eurasian Steppe.

"[271][note 53] The oldest inscriptions in Old Indic, the language of the Rig Veda, is found not in India, but in northern Syria in Hittite records[112] regarding one of their neighbors, the Hurrian-speaking Mitanni.

[citation needed] According to Romila Thapar, the Srauta Sutra of Baudhayana "refers to the Parasus and the arattas who stayed behind and others who moved eastwards to the middle Ganges valley and the places equivalent such as the Kasi, the Videhas and the Kuru Pancalas, and so on.

[web 1]The Indus Valley civilisation was localised, that is, urban centers disappeared and were replaced by local cultures, due to a climatic change that is also signalled for the neighbouring areas of the Middle East.

[298] The Indian monsoon declined and aridity increased, with the Ghaggar-Hakra retracting its reach towards the foothills of the Himalaya,[298][301][302] leading to erratic and less extensive floods that made inundation agriculture less sustainable.

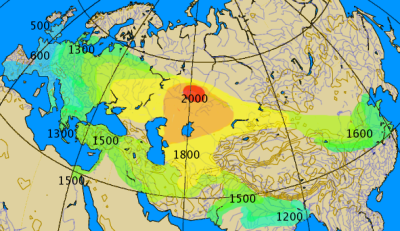

– Center: Steppe cultures

1 (black): Anatolian languages (archaic PIE)

2 (black): Afanasievo culture (early PIE)

3 (black) Yamnaya culture expansion (Pontic-Caspian steppe, Danube Valley) (late PIE)

4A (black): Western Corded Ware

4B-C (blue & dark blue): Bell Beaker; adopted by Indo-European speakers

5A-B (red): Eastern Corded ware

5C (red): Sintashta (proto-Indo-Iranian)

6 (magenta): Andronovo

7A (purple): Indo-Aryans (Mittani)

7B (purple): Indo-Aryans (India)

[NN] (dark yellow): proto-Balto-Slavic

8 (grey): Greek

9 (yellow):Iranians

– [not drawn]: Armenian, expanding from western steppe