Proto-Min

Min varieties developed in the relative isolation of the Chinese province of Fujian and eastern Guangdong, and have since spread to Taiwan, Southeast Asia, and other parts of the world.

A two-way contrast in sonorants is also reconstructed, compared with the single series of Middle Chinese and all modern varieties.

Evidence from early loans into other languages suggests that the additional contrasts may reflect consonant clusters or minor syllables.

After the area was first settled by Chinese during the Han dynasty, most subsequent migration from north to south China passed through the valleys of the Xiang and Gan rivers to the west.

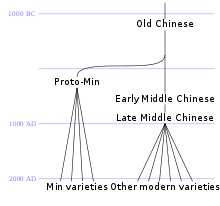

[10] Baxter and Sagart suggest that the later part of the Proto-Min period may have overlapped with Early Middle Chinese.

[13] Some of the distinctive Jiangdong words mentioned by Guo Pu appear to be preserved in modern Min varieties, including Proto-Min *giA 'leech' and *lhɑnC 'young fowl'.

[14] This language entered Fujian after the area was opened to Chinese settlement by the defeat of the Minyue state by the armies of Emperor Wu of Han in 110 BC.

[15] Norman argues that Hakka and Yue have resulted from overlays of this language by successive waves of influence from northern China.

[16] When Chinese soldiers and settlers moved south from their homeland in the North China Plain, they came into contact with speakers of Tai–Kadai, Hmong–Mien and Austroasiatic languages.

[22][23] However, in a 1963 report on a survey of Fujian, Pan Maoding and colleagues argued that the primary split was between inland and coastal groups.

In the Shaojiang dialects, spoken in the northwestern Fujian counties of Shaowu and Jiangle, the reflexes of Middle Chinese voiced stops are uniformly aspirated, as in Gan and Hakka, leading some workers to assign them to one of these groups.

[27] However, Norman showed that their tonal development could only be explained in terms of the same two classes of voiced initial assumed for Min dialects.

[29][30] In a series of papers from 1973, Jerry Norman sought to reconstruct the initial consonants of Proto-Min by applying the comparative method to pronunciations in modern Min varieties.

For this purpose, rather than the traditional approach of soliciting readings of character lists, he focussed on everyday vocabulary and excluded words of literary origin.

[31] The inventory of Proto-Min initials differs from that of Middle Chinese (as deduced from the Qieyun rhyme book and its successors) in several ways: The most controversial have been the "softened" stops and affricates, so named because they have lateral or fricative reflexes in some Northern Min varieties centred on Jianyang.

These initials also have distinct tonal reflexes in the Northern Min and Shaojiang groups, but have merged with unaspirated stops and affricates in coastal varieties.

[57] Inland Min varieties are characterized by having two distinct reflexes of Middle Chinese /l/, which Norman labels as Proto-Min *l and *lh.

In modern Southern Min varieties such as Hokkien, /l/ and /n/ comprise a single phoneme, realized as /n/ before nasalized vowels and as /l/ in other syllables.

[74] As with Middle Chinese and other languages of the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, each of these classes split into upper and lower registers, depending on whether the original initial was voiceless or voiced.

[97][98] Proto-Min also had a single word with a syllabic nasal, the usual negator *mC (cognate with Middle Chinese mjɨjH 未 'not have').