Standard Chinese

"[20] However, the sense of Guoyu as a specific language variety promoted for general use by the citizenry was originally borrowed from Japan in the early 20th century.

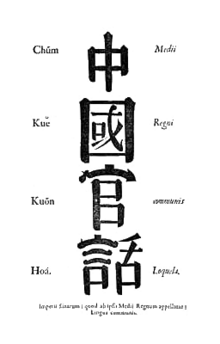

The term Guanhua (官話; 官话; 'official speech') was used during the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1912) dynasties to refer to the lingua franca spoken within the imperial courts.

[40] Following the end of the Chinese Civil War, the People's Republic of China (PRC) continued standardisation efforts on the mainland, and in 1955 officially began using Putonghua (普通话; 普通話; 'common speech') instead of Guoyu, which remains the name used in Taiwan.

The forms of Standard Chinese used in China and Taiwan have diverged somewhat since the end of the Civil War, especially in newer vocabulary, and a little in pronunciation.

[48] In both mainland China and Taiwan, Standard Chinese is used in most official contexts, as well as the media and educational system, contributing to its proliferation.

In many areas, especially in southern China, it is commonly used for practical reasons, as linguistic diversity is so great that residents of neighboring cities may have difficulties communicating with each other without a lingua franca.

[51] Throughout the country, Standard Chinese has heavily influenced local languages through diglossia, replacing them entirely in some cases, especially among younger people in urban areas.

However, regulations enacted by local governments to implement the national law have included measures to control the use of spoken dialects and traditional characters in writing.

Government employees, including teachers, conference holders, broadcasters, and TV staff are required to use Standard Chinese.

[53] [54] In addition, public signage is to be written using simplified characters, with exceptions for historical sites, pre-registered logos, or when approved by the state.

Meanwhile, those from urban areas—as well as younger speakers, who have received their education primarily in Standard Chinese—are almost all fluent in it, with some being unable to speak their local dialect.

In the summer of 2010, reports of a planned increase in the use of the Putonghua on local television in Guangdong led to demonstrations on the streets by thousands of Cantonese-speaking citizens.

During the period of martial law between 1949 and 1987, the Taiwanese government revived the Mandarin Promotion Council, discouraging or in some cases forbidding the use of Hokkien and other non-standard varieties.

Starting in the 2000s during the administration of President Chen Shui-Bian, the Taiwanese government began making efforts to recognize the country's other languages.

They began being taught in schools, and their use increased in media, though Standard Chinese remains the country's lingua franca.

Meanwhile, a colloquial form called Singdarin is used in informal daily life and is heavily influenced in terms of both grammar and vocabulary by local languages such as Cantonese, Hokkien, and Malay.

In Singapore, the government has heavily promoted a "Speak Mandarin Campaign" since the late 1970s, with the use of other Chinese varieties in broadcast media being prohibited and their use in any context officially discouraged until recently.

Lee Kuan Yew, the initiator of the campaign, admitted that to most Chinese Singaporeans, Mandarin was a "stepmother tongue" rather than a true mother language.

[69] In Malaysia, Mandarin has been adopted by local Chinese-language schools as the medium of instruction with the standard shared with Singaporean Chinese.

After the second grade, the entire educational system is in Standard Chinese, except for local language classes that have been taught for a few hours each week in Taiwan starting in the mid-1990s.

Employers often require a level of Standard Chinese proficiency from applicants depending on the position, and many university graduates on the mainland take the PSC before looking for a job.

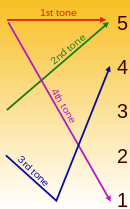

There are four tonal categories, marked in pinyin with diacritics, as in the words mā (媽; 妈; 'mother'), má (麻; 'hemp'), mǎ (馬; 马; 'horse') and mà (罵; 骂; 'curse').

It is common for Standard Chinese to be spoken with the speaker's regional accent, depending on factors such as age, level of education, and the need and frequency to speak in official or formal situations.

Distinctive features of the Beijing dialect are more extensive use of erhua in vocabulary items that are left unadorned in descriptions of the standard such as the Xiandai Hanyu Cidian, as well as more neutral tones.

While the Standard Chinese spoken in Taiwan is nearly identical to that of mainland China, the colloquial form has been heavily influenced by other local languages, especially Taiwanese Hokkien.

[88] The stereotypical "southern Chinese" accent does not distinguish between retroflex and alveolar consonants, pronouncing pinyin zh [tʂ], ch [tʂʰ], and sh [ʂ] in the same way as z [ts], c [tsʰ], and s [s] respectively.

[90] Chinese is a strongly analytic language, having almost no inflectional morphemes, and relying on word order and particles to express relationships between the parts of a sentence.

Many honorifics used in imperial China are also used in daily conversation in modern Mandarin, such as jiàn (賤; 贱; '[my] humble') and guì (貴; 贵; '[your] honorable').

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Standard Chinese:[107] 人人生而自由,在尊严和权利上一律平等。他们赋有理性和良心,并应以兄弟关系的精神相对待。人人生而自由,在尊嚴和權利上一律平等。他們賦有理性和良心,並應以兄弟關係的精神相對待。Rén rén shēng ér zìyóu, zài zūnyán hé quánlì shàng yīlǜ píngděng.

Tāmen fùyǒu lǐxìng hé liángxīn, bìng yīng yǐ xiōngdì guānxì de jīngshén xiāng duìdài.