Quasicrystal

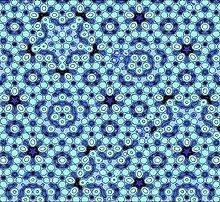

In crystallography the quasicrystals were predicted in 1981 by a five-fold symmetry study of Alan Lindsay Mackay,[4]—that also brought in 1982, with the crystallographic Fourier transform of a Penrose tiling,[5] the possibility of identifying quasiperiodic order in a material through diffraction.

Symmetrical diffraction patterns result from the existence of an indefinitely large number of elements with a regular spacing, a property loosely described as long-range order.

In 1982, materials scientist Dan Shechtman observed that certain aluminium–manganese alloys produced unusual diffractograms, which today are seen as revelatory of quasicrystal structures.

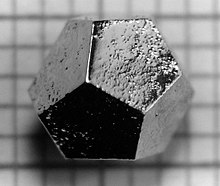

Observed in a rapidly solidified Al-Mn alloy, quasicrystals exhibited icosahedral symmetry, which was previously thought impossible in crystallography.

Despite initial skepticism, the discovery gained widespread acceptance, prompting the International Union of Crystallography to redefine the term "crystal.

"[11] The work ultimately earned Shechtman the 2011 Nobel Prize in Chemistry[12] and inspired significant advancements in materials science and mathematics.

On 25 October 2018, Luca Bindi and Paul Steinhardt were awarded the Aspen Institute 2018 Prize for collaboration and scientific research between Italy and the United States, after they discovered icosahedrite, the first quasicrystal known to occur naturally.

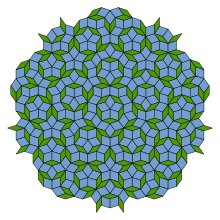

The first representations of perfect quasicrystalline patterns can be found in several early Islamic works of art and architecture such as the Gunbad-i-Kabud tomb tower, the Darb-e Imam shrine and the Al-Attarine Madrasa.

They went unnoticed at the time of the test but were later identified in samples of red trinitite, a glass-like substance formed from fused sand and copper transmission lines.

In 1972, R. M. de Wolf and W. van Aalst[19] reported that the diffraction pattern produced by a crystal of sodium carbonate cannot be labeled with three indices but needed one more, which implied that the underlying structure had four dimensions in reciprocal space.

[21][22] Dan Shechtman first observed ten-fold electron diffraction patterns in 1982, while conducting a routine study of an aluminium–manganese alloy, Al6Mn, at the US National Bureau of Standards (later NIST).

[27] The observation of the ten-fold diffraction pattern lay unexplained for two years until the spring of 1984, when Blech asked Shechtman to show him his results again.

A quick study of Shechtman's results showed that the common explanation for a ten-fold symmetrical diffraction pattern, a type of crystal twinning, was ruled out by his experiments.

He decided to use a computer simulation to calculate the diffraction intensity from a cluster of such a material, which he termed as "multiple polyhedral", and found a ten-fold structure similar to what was observed.

[29] Meanwhile, on seeing the draft of the paper, John Cahn suggested that Shechtman's experimental results merit a fast publication in a more appropriate scientific journal.

[33] In 1992, the International Union of Crystallography altered its definition of a crystal, reducing it to the ability to produce a clear-cut diffraction pattern and acknowledging the possibility of the ordering to be either periodic or aperiodic.

[8][34] In 2001, Steinhardt hypothesized that quasicrystals could exist in nature and developed a method of recognition, inviting all the mineralogical collections of the world to identify any badly cataloged crystals.

In 2007 Steinhardt received a reply by Luca Bindi, who found a quasicrystalline specimen from Khatyrka in the University of Florence Mineralogical Collection.

[36] A further study of Khatyrka meteorites revealed micron-sized grains of another natural quasicrystal, which has a ten-fold symmetry and a chemical formula of Al71Ni24Fe5.

"His discovery of quasicrystals revealed a new principle for packing of atoms and molecules," stated the Nobel Committee and pointed that "this led to a paradigm shift within chemistry.

In 2009, it was found that thin-film quasicrystals can be formed by self-assembly of uniformly shaped, nano-sized molecular units at an air-liquid interface.

[44] In 2018, chemists from Brown University announced the successful creation of a self-constructing lattice structure based on a strangely shaped quantum dot.

The aperiodic nature of quasicrystals can also make theoretical studies of physical properties, such as electronic structure, difficult due to the inapplicability of Bloch's theorem.

[53] Study of quasicrystals may shed light on the most basic notions related to the quantum critical point observed in heavy fermion metals.

Therefore, the excitation around the roton instabilities would grow exponentially and form multiple allowed lattice constants leading to quasi-ordered periodic droplet crystals.

[62] Recent studies show typically brittle quasicrystals can exhibit remarkable ductility of over 50% strains at room temperature and sub-micrometer scales (<500 nm).

When Shechtman was asked about potential applications of quasicrystals he said that a precipitation-hardened stainless steel is produced that is strengthened by small quasicrystalline particles.