Radiation-absorbent material

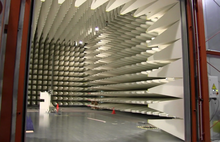

One of the most effective types of RAM comprises arrays of pyramid-shaped pieces, each of which is constructed from a suitably lossy material.

Typically pyramidal RAM will comprise a rubberized foam material impregnated with controlled mixtures of carbon and iron.

This incoherent scattering also occurs within the foam structure, with the suspended carbon particles promoting destructive interference.

With each bounce, the wave loses energy to the foam material and thus exits with lower signal strength.

This type has a smaller effective frequency range than the pyramidal RAM and is designed to be fixed to good conductive surfaces.

Its performance might however be quite adequate if tests are limited to lower frequencies (ferrite plates have a damping curve that makes them most effective between 30–1000 MHz).

[4] The earliest forms of stealth coating were radar absorbing paints developed by Major K. Mano of the Tama Technical Institute, and Dr. Shiba of the Tokyo Engineering College for the IJAAF.

Despite success in laboratory tests, the paints saw little practical application as they were heavy and would significantly impact the performance of any aircraft they were applied to.

Rubber and plastic with carbon powder with varying ratios were layered to absorb and disperse radar waves.

Work on the program was halted due to allied bombing raids, but research was continued post war by the Americans to mild success.

The adhesive which bonded plywood sheets in its skin was impregnated with graphite particles which were intended to reduce its visibility to Britain's radar.

Then, during the panel fabrication process, while the paint is still liquid, a magnetic field is applied with a specific Gauss strength and at a specific distance to create magnetic field patterns in the carbonyl iron balls within the liquid paint ferrofluid.

The plane is covered in tiles "glued" to the fuselage and the remaining gaps are filled with iron ball "glue.

"[citation needed] The United States Air Force introduced a radar-absorbent paint made from both ferrofluidic and nonmagnetic substances.

[citation needed] This material typically consists of a fireproofed urethane foam loaded with conductive carbon black [carbonyl iron spherical particles, and/or crystalline graphite particles] in mixtures between 0.05% and 0.1% (by weight in finished product), and cut into square pyramids with dimensions set specific to the wavelengths of interest.

Incoherent scattering also occurs within the foam structure, with the suspended conductive particles promoting destructive interference.

Therefore, in applications where high radar energies are involved, cooling fans are used to exhaust the heat generated.

[citation needed] When first introduced in 1943, the Jaumann layer consisted of two equally spaced reflective surfaces and a conductive ground plane.

SRR technology is particularly effective when used on faceted shapes that have perfectly flat surfaces that present no direct reflections back to the radar source (such as the F-117A).

This technology uses photographic process to create a resist layer on a thin (about 0.18 mm or 0.007 in) copper foil on a dielectric backing (thin circuit board material) etched into tuned resonator arrays, each individual resonator being in a "C" shape (or other shape—such as a square).

[citation needed] Radars work in the microwave frequency range, which can be absorbed by multi-wall nanotubes (MWNTs).

It has been found that in addition to the radar absorbing properties, the nanotubes neither reflect nor scatter visible light, making it essentially invisible at night, much like painting current stealth aircraft black except much more effective.