Isotopes of iodine

Cosmogenic sources of 129I produce very tiny quantities of it that are too small to affect atomic weight measurements; iodine is thus also a mononuclidic element—one that is found in nature only as a single nuclide.

Unavoidable in situ production of this isotope is important in nuclear reactor control, as it decays to 135Xe, the most powerful known neutron absorber, and the nuclide responsible for the so-called iodine pit phenomenon.

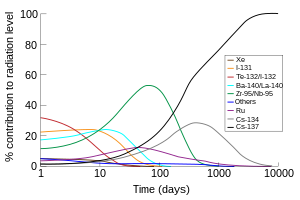

Due to its volatility, short half-life, and high abundance in fission products, 131I (along with the short-lived iodine isotope 132I, which is produced from the decay of 132Te with a half-life of 3 days) is responsible for the largest part of radioactive contamination during the first week after accidental environmental contamination from the radioactive waste from a nuclear power plant.

Thus highly dosed iodine supplements (usually potassium iodide) are given to the populace after nuclear accidents or explosions (and in some cases prior to any such incident as a civil defense mechanism) to reduce the uptake of radioactive iodine compounds by the thyroid before the highly radioactive isotopes have had time to decay.

123I, which has no beta activity, is more suited for routine nuclear medicine imaging of the thyroid and other medical processes and less damaging internally to the patient.

Iodine-125 is the only other iodine radioisotope used in radiation therapy, but only as an implanted capsule in brachytherapy, where the isotope never has a chance to be released for chemical interaction with the body's tissues.

Following EC, the excited 123Te from 123I emits a high-speed 127 keV internal conversion electron (not a beta ray) about 13% of the time, but this does little cellular damage due to the nuclide's short half-life and the relatively small fraction of such events.

Both 123I and 125I emit copious low energy Auger electrons after their decay, but these do not cause serious damage (double-stranded DNA breaks) in cells, unless the nuclide is incorporated into a medication that accumulates in the nucleus, or into DNA (this is never the case is clinical medicine, but it has been seen in experimental animal models).

The low energy of the gamma spectrum in this case limits radiation damage to tissues far from the implanted capsule.

[10] In this use, the nuclide is chemically bonded to a pharmaceutical to form a positron-emitting radiopharmaceutical, and injected into the body, where again it is imaged by PET scan.

This makes it fairly easy for 129I to enter the biosphere as it becomes incorporated into vegetation, soil, milk, animal tissue, etc.

Excesses of stable 129Xe in meteorites have been shown to result from decay of "primordial" iodine-129 produced newly by the supernovas that created the dust and gas from which the solar system formed.

Its decay is the basis of the I-Xe iodine-xenon radiometric dating scheme, which covers the first 85 million years of Solar System evolution.

It is thought to cause the majority of excess thyroid cancers seen after nuclear fission contamination (such as bomb fallout or severe nuclear reactor accidents like the Chernobyl disaster) However, these epidemiological effects are seen primarily in children, and treatment of adults and children with therapeutic 131I, and epidemiology of adults exposed to low-dose 131I has not demonstrated carcinogenicity.

Iodine fission-produced isotopes not discussed above (iodine-128, iodine-130, iodine-132, and iodine-133) have half-lives of several hours or minutes, rendering them almost useless in other applicable areas.

In theory, many harmful late-cancer effects of nuclear fallout might be prevented in this way, since an excess of thyroid cancers, presumably due to radioiodine uptake, is the only proven radioisotope contamination effect after a fission accident, or from contamination by fallout from an atomic bomb (prompt radiation from the bomb also causes other cancers, such as leukemias, directly).

Taking large amounts of iodide saturates thyroid receptors and prevents uptake of most radioactive iodine-131 that may be present from fission product exposure (although it does not protect from other radioisotopes, nor from any other form of direct radiation).

The protective effect of KI lasts approximately 24 hours, so must be dosed daily until a risk of significant exposure to radioiodines from fission products no longer exists.