Radioisotope thermoelectric generator

RTGs have been used as power sources in satellites, space probes, and uncrewed remote facilities such as a series of lighthouses built by the Soviet Union inside the Arctic Circle.

RTGs were developed in the US during the late 1950s by Mound Laboratories in Miamisburg, Ohio, under contract with the United States Atomic Energy Commission.

[6] The first RTG launched into space by the United States was SNAP 3B in 1961 powered by 96 grams of plutonium-238 metal, aboard the Navy Transit 4A spacecraft.

RTGs were also used instead of solar panels to power the two Viking landers, and for the scientific experiments left on the Moon by the crews of Apollo 12 through 17 (SNAP 27s).

Because the Apollo 13 Moon landing was aborted, its RTG rests in the South Pacific Ocean, in the vicinity of the Tonga Trench.

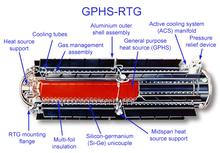

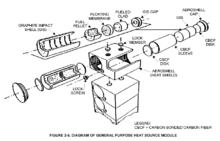

The design of an RTG is simple by the standards of nuclear technology: the main component is a sturdy container of a radioactive material (the fuel).

Heat is produced through spontaneous radioactive decay at a non-adjustable and steadily decreasing rate that depends only on the amount of fuel isotope and its half-life.

Therefore, auxiliary power supplies (such as rechargeable batteries) may be needed to meet peak demand, and adequate cooling must be provided at all times including the pre-launch and early flight phases of a space mission.

While spectacular failures like a nuclear meltdown or explosion are impossible with an RTG, there is still a risk of radioactive contamination if the rocket explodes, the device reenters the atmosphere and disintegrates, terrestrial RTGs are damaged by storms or seasonal ice, or are vandalized.

Because the system is working with a criticality close to but less than 1, i.e. Keff < 1, a subcritical multiplication is achieved which increases the neutron background and produces energy from fission reactions.

[18] This could support mission extensions up to 1000 years on the interstellar probe, because the power output would decline more slowly over the long term than plutonium.

A typical RTG is powered by radioactive decay and features electricity from thermoelectric conversion, but for the sake of knowledge, some systems with some variations on that concept are included here.

Plutonium extracted from spent nuclear fuel has a low share of Pu-238, so plutonium-238 for use in RTGs is usually purpose-made by neutron irradiation of neptunium-237, further raising costs.

Caesium in fission products is almost equal parts Cs-135 and Cs-137, plus significant amounts of stable Cs-133 and, in "young" spent fuel, short lived Cs-134.

As Sr-90, Cs-137 and other lighter radionuclides cannot maintain a nuclear chain reaction under any circumstances, RTGs of arbitrary size and power could be assembled from them if enough material can be produced.

In general, however, potential applications for such large-scale RTGs are more the domain of small modular reactors, microreactors or non-nuclear power sources.

Plutonium-238 has a half-life of 87.7 years, reasonable power density of 0.57 watts per gram,[36] and exceptionally low gamma and neutron radiation levels.

The reduction of the oxygen-17 and oxygen-18 present in the plutonium dioxide will result in a much lower neutron emission rate for the oxide; this can be accomplished by a gas phase 16O2 exchange method.

If this plan is funded, the goal would be to set up automation and scale-up processes in order to produce an average of 1.5 kg (3.3 lb) per year by 2025.

This isotope provides phenomenal power density (pure 210Po emits 140 W/g) because of its high decay rate, but has limited use because of its very short half-life of 138 days.

While the short half-life also reduces the time during which accidental release to the environment is a concern, polonium-210 is extremely radiotoxic if ingested and can cause significant harm even in chemically inert forms, which pass through the digestive tract as a "foreign object".

However, if a sufficient demand for polonium-210 exists, its extraction could be worthwhile similar to how tritium is economically recovered from the heavy water moderator in CANDUs.

With a current global shortage[45] of 238Pu, 241Am is being studied as RTG fuel by ESA[44][46] and in 2019, UK's National Nuclear Laboratory announced the generation of usable electricity.

[48] By 2022, these numbers had dropped to around 220 W.[49] NASA has developed a multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator (MMRTG) in which the thermocouples would be made of skutterudite, a cobalt arsenide (CoAs3), which can function with a smaller temperature difference than the current tellurium-based designs.

To minimize the risk of the radioactive material being released, the fuel is stored in individual modular units with their own heat shielding.

There have been several known accidents involving RTG-powered spacecraft: One RTG, the SNAP-19C, was lost near the top of Nanda Devi mountain in India in 1965 when it was stored in a rock formation near the top of the mountain in the face of a snowstorm before it could be installed to power a CIA remote automated station collecting telemetry from the Chinese rocket testing facility.

[64][page needed] Many Beta-M RTGs produced by the Soviet Union to power lighthouses and beacons have become orphaned sources of radiation.

Several of these units have also been illegally dismantled for scrap metal, or been exposed to storm conditions, freezing and water penetration, common issues in those abandoned in the harsh Russian arctic.

The US Department of Defense cooperative threat reduction program has expressed concern that material from the Beta-M RTGs can be used by terrorists to construct a dirty bomb.

Mechanical degradation of "pebbles" or larger objects into fine dust is more likely and could disperse the material over a wider area, however this would also reduce the risk of any single exposure event resulting in a high dose.