Reactions to On the Origin of Species

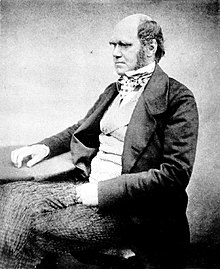

The immediate reactions, from November 1859 to April 1861, to On the Origin of Species, the book in which Charles Darwin described evolution by natural selection, included international debate, though the heat of controversy was less than that over earlier works such as Vestiges of Creation.

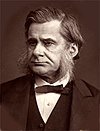

Darwin monitored the debate closely, cheering on Thomas Henry Huxley's battles with Richard Owen to remove clerical domination of the scientific establishment.

Religious views were mixed, with the Church of England's scientific establishment reacting against the book, while liberal Anglicans strongly supported Darwin's natural selection as an instrument of God's design.

Both sides came away feeling victorious, but Huxley went on to depict the debate as pivotal in a struggle between religion and science and used Darwinism to campaign against the authority of the clergy in education, as well as daringly advocating the "Ape Origin of Man".

By the 1840s Darwin became friends with the young botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker who had followed his father into the science, and after going on a survey voyage used his contacts to eventually find a position.

[3] In the 1850s Darwin met Thomas Huxley, an ambitious naturalist who had returned from a long survey trip but lacked the family wealth or contacts to find a career[4] and who joined the progressive group around Herbert Spencer looking to make science a profession, freed from the clerics.

Dissident clergymen even began questioning accepted premises of Christian morality, and Benjamin Jowett's 1855 commentary on St. Paul brought a storm of controversy.

On 18 June 1858 he received a parcel from Alfred Russel Wallace enclosing about twenty pages describing an evolutionary mechanism that was similar to Darwin's own theory.

Four days before publication, a review in the authoritative Athenaeum[7] [8] (by John Leifchild, published anonymously, as was the custom at that time) was quick to pick out the unstated implications of "men from monkeys" already controversial from Vestiges, saw snubs to theologians, summing up Darwin's "creed" as man "was born yesterday – he will perish tomorrow" and concluded that "The work deserves attention, and will, we have no doubt, meet with it.

[11] Hooker had been "converted", Lyell was "absolutely gloating" and Huxley wrote "with such tremendous praise", advising that he was sharpening his "beak and claws" to disembowel "the curs who will bark and yelp".

[12][13] Richard Owen had been the first to respond to the complimentary copies, courteously claiming that he had long believed that "existing influences" were responsible for the "ordained" birth of species.

"[41] In April he continued, "It is curious that I remember well time when the thought of the eye made me cold all over, but I have got over this stage of the complaint, & now small trifling particulars of structure often make me very uncomfortable.

Martineau sent her thanks, adding that she had previously praised "the quality & conduct of your brother's mind, but it is an unspeakable satisfaction to see here the full manifestation of its earnestness & simplicity, its sagacity, its industry, & the patient power by wh.

John Stevens Henslow, the botany professor whose natural history course Charles had joined thirty years earlier, gave faint praise to the Origin as "a stumble in the right direction" but distanced himself from its conclusions, "a question past our finding out..."[47] The Anglican establishment predominantly opposed Darwin.

While Prince Albert supported the idea, after the publication of the Origin Queen Victoria's ecclesiastical advisers, including the Bishop of Oxford Samuel Wilberforce, dissented and the request was denied.

There was no official comment from the Vatican for several decades, but in 1860 a council of the German Catholic bishops pronounced that the belief that "man as regards his body, emerged finally from the spontaneous continuous change of imperfect nature to the more perfect, is clearly opposed to Sacred Scripture and to the Faith."

[49] On 10 February 1860 Huxley gave a lecture titled On Species and Races, and their Origin at the Royal Institution,[50] reviewing Darwin's theory with fancy pigeons on hand to demonstrate artificial selection, as well as using the occasion to confront the clergy with his aim of wresting science from ecclesiastical control.

He referred to Galileo's persecution by the church, "the little Canutes of the hour enthroned in solemn state, bidding that great wave to stay, and threatening to check its beneficent progress."

[51] To Darwin such rhetoric was "time wasted" and on reflection he thought the lecture "an entire failure which gave no just idea of natural selection,"[50] but by March he was listing those on "our side" as against the "outsiders."

"[52] The position of Richard Owen was unknown: when emphasising to a Parliamentary committee the need for a new Natural History museum, he pointed out that "The whole intellectual world this year has been excited by a book on the origin of species; and what is the consequence?

Everybody has read Mr. Darwin's book, or, at least, has given an opinion upon its merits or demerits; pietists, whether lay or ecclesiastic, decry it with the mild railing which sounds so charitable; bigots denounce it with ignorant invective; old ladies of both sexes consider it a decidedly dangerous book, and even savants, who have no better mud to throw, quote antiquated writers to show that its author is no better than an ape himself; while every philosophical thinker hails it as a veritable Whitworth gun in the armoury of liberalism; and all competent naturalists and physiologists, whatever their opinions as to the ultimate fate of the doctrines put forth, acknowledge that the work in which they are embodied is a solid contribution to knowledge and inaugurates a new epoch in natural history.

As well as attacking Darwin's "disciples" Hooker and Huxley, he thought that the book symbolised the sort of "abuse of science to which a neighbouring nation, some seventy years since, owed its temporary degradation.

His most prominent critic, John Phillips, had investigated how temperatures increased with depth in the 1830s, and was convinced that, contrary to Lyell and Darwin's uniformitarianism, the Earth was cooling over the long term.

[59] Most reviewers wrote with great respect, deferring to Darwin's eminent position in science though finding it hard to understand how natural selection could work without a divine selector.

[60] The Saturday Review reported that "The controversy excited by the appearance of Darwin's remarkable work on the Origin of Species has passed beyond the bounds of the study and lecture-room into the drawing-room and the public street.

"[61] The older generation of Darwin's tutors were rather negative, and later in May he told his cousin Fox that "the attacks have been falling thick & heavy on my now case-hardened hide.— Sedgwick & Clarke opened regular battery on me lately at Cambridge Phil.

[63] In June, Karl Marx saw the book as a "bitter satire" that showed "a basis in natural science for class struggle in history", in which "Darwin recognizes among beasts and plants his English society".

While there was no formal debate organised on the issue, Professor John William Draper of New York University was to talk on Darwin and social progress at a routine "Botany and Zoology" meeting.

[77] Darwin quoted a proverb: "A bench of bishops is the devil's flower garden", and joined others including Lyell, though not Hooker and Huxley, in signing a counter-letter supporting Essays and Reviews for trying to "establish religious teachings on a firmer and broader foundation".

[79] On 20 November, Darwin told Lyell of his revisions for a third edition of the Origin, including removing his estimate of the time it took for the Weald to erode: "The confounded Wealden calculation, to be struck out.