Reason

For example, reasoning is the means by which rational individuals understand the significance of sensory information from their environments, or conceptualize abstract dichotomies such as cause and effect, truth and falsehood, or good and evil.

Reasoning, as a part of executive decision making, is also closely identified with the ability to self-consciously change, in terms of goals, beliefs, attitudes, traditions, and institutions, and therefore with the capacity for freedom and self-determination.

The earliest major philosophers to publish in English, such as Francis Bacon, Thomas Hobbes, and John Locke also routinely wrote in Latin and French, and compared their terms to Greek, treating the words "logos", "ratio", "raison" and "reason" as interchangeable.

Within the human mind or soul (psyche), reason was described by Plato as being the natural monarch which should rule over the other parts, such as spiritedness (thumos) and the passions.

[15] But teleological accounts such as Aristotle's were highly influential for those who attempt to explain reason in a way that is consistent with monotheism and the immortality and divinity of the human soul.

The Neoplatonic conception of the rational aspect of the human soul was widely adopted by medieval Islamic philosophers and continues to hold significance in Iranian philosophy.

[15] As European intellectual life reemerged from the Dark Ages, the Christian Patristic tradition and the influence of esteemed Islamic scholars like Averroes and Avicenna contributed to the development of the Scholastic view of reason, which laid the foundation for our modern understanding of this concept.

Other Scholastics, such as Roger Bacon and Albertus Magnus, following the example of Islamic scholars such as Alhazen, emphasised reason an intrinsic human ability to decode the created order and the structures that underlie our experienced physical reality.

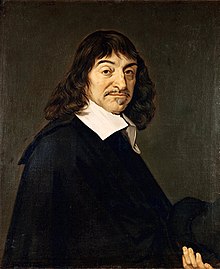

In his search for a foundation of all possible knowledge, Descartes decided to throw into doubt all knowledge—except that of the mind itself in the process of thinking: At this time I admit nothing that is not necessarily true.

[citation needed][30] In the formulation of Kant, who wrote some of the most influential modern treatises on the subject, the great achievement of reason (German: Vernunft) is that it is able to exercise a kind of universal law-making.

[32] According to Kant, in a free society each individual must be able to pursue their goals however they see fit, as long as their actions conform to principles given by reason.

[33]In contrast to Hume, Kant insisted that reason itself (German Vernunft) could be used to find solutions to metaphysical problems, especially the discovery of the foundations of morality.

Others, including Hegel, believe that it has obscured the importance of intersubjectivity, or "spirit" in human life, and they attempt to reconstruct a model of what reason should be.

[44][45] Psychologist David Moshman, citing Bickhard and Campbell, argues for a "metacognitive conception of rationality" in which a person's development of reason "involves increasing consciousness and control of logical and other inferences".

Aristotle asserted that phantasia (imagination: that which can hold images or phantasmata) and phronein (a type of thinking that can judge and understand in some sense) also exist in some animals.

Explaining reason from this direction: human thinking is special in that we often understand visible things as if they were themselves images of our intelligible "objects of thought" as "foundations" (hypothēses in Ancient Greek).

Tolkien wrote in his essay "On Fairy Stories" that the terms "fantasy" and "enchantment" are connected to not only "the satisfaction of certain primordial human desires" but also "the origin of language and of the mind".

Since classical antiquity a question has remained constant in philosophical debate (sometimes seen as a conflict between Platonism and Aristotelianism) concerning the role of reason in confirming truth.

In Greek, "first principles" are archai, "starting points",[71] and the faculty used to perceive them is sometimes referred to in Aristotle[72] and Plato[73] as nous which was close in meaning to awareness or consciousness.

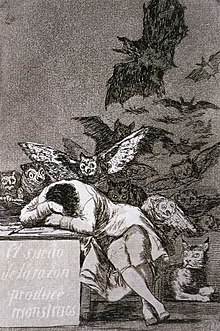

[citation needed] Reason has been seen as cold, an "enemy of mystery and ambiguity",[80] a slave, or judge, of the passions, notably in the work of David Hume.

According to Richard Velkley, "Rousseau outlines certain programs of rational self-correction, most notably the political legislation of the Contrat Social and the moral education in Émile.

"[This quote needs a citation] This quandary presented by Rousseau led to Kant's new way of justifying reason as freedom to create good and evil.

In various ways, German Idealism after Kant, and major later figures such Nietzsche, Bergson, Husserl, Scheler, and Heidegger, remain preoccupied with problems coming from the metaphysical demands or urges of reason.

Damasio argues that these somatic markers (known collectively as "gut feelings") are "intuitive signals" that direct our decision making processes in a certain way that cannot be solved with rationality alone.

[86] Though theologies and religions such as classical monotheism typically do not admit to being irrational, there is often a perceived conflict or tension between faith and tradition on the one hand, and reason on the other, as potentially competing sources of wisdom, law, and truth.

In the other animals, community [koinōnia] goes no further than this, but people live together [sumoikousin] not only for the sake of making children, but also for the things for life; for from the start the functions [erga] are divided, and are different for man and woman.

[6]: VIII.12 Rousseau in his Second Discourse finally took the shocking step of claiming that this traditional account has things in reverse: with reason, language, and rationally organized communities all having developed over a long period of time merely as a result of the fact that some habits of cooperation were found to solve certain types of problems, and that once such cooperation became more important, it forced people to develop increasingly complex cooperation—often only to defend themselves from each other.

As a result, he claimed, living together in rationally organized communities like modern humans is a development with many negative aspects compared to the original state of man as an ape.

According to Rousseau, we should even doubt that reason, language, and politics are a good thing, as opposed to being simply the best option given the particular course of events that led to today.

Rousseau's theory, that human nature is malleable rather than fixed, is often taken to imply (for example by Karl Marx) a wider range of possible ways of living together than traditionally known.