Reign of Alfonso XIII

The death of the king, with no male offspring —Alfonso and María Cristina, who had married on 29 November 1879, had had two daughters— and with a third child to be born, as the queen was three months pregnant, created great uncertainty about the future of the Restoration regime, which had only ten years to live, as the supposed "power vacuum" could be exploited by the Carlists or the Republicans to put an end to it.

But anarchist terrorism also played a certain role internally, with the most important attack taking place in Barcelona on 7 June 1896 during the Corpus Christi procession in Canvis Nous Street, in which six people died on the spot and another forty-two were injured.

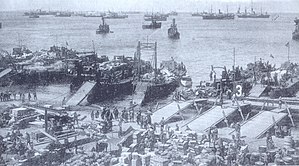

[24] In February 1898 the American battleship Maine sank in the port of Havana where it was anchored as a result of an explosion —264 sailors and two officers died— and two months later the United States Congress passed a resolution demanding Spain's independence from Cuba and authorized President McKinley to declare war, which he did on April 25.

[31] The only important opposition movement that Silvela's conservative government had to face was the taxpayers' strike —or "tancament de caixes", literally 'closing of the cashboxes', in Catalonia— promoted between April and July 1900 by the National League of Producers, an organization created by the regenerationist Joaquín Costa, and by the Chambers of Commerce, directed by Basilio Paraíso.

[32] The internal disagreements —mainly the result of General Polavieja's opposition to the reduction of public spending imposed by Fernández Villaverde to achieve a balanced budget, since it clashed with his request for greater economic allocations to modernize the Army— were what ended up causing the fall of Silvela's government in October 1900.

[41] Thus when in December 1903 the conservative Antonio Maura came to the government, the Republicans spoke of a new "oriental" crisis, adding that it had had "feminine" touches, alluding to the alleged intervention of the queen mother, the former regent María Cristina de Habsburgo-Lorena.

[42] The first important case of interventionism in the political life of Alfonso XIII took place in December 1904, when he refused to endorse the proposal for the appointment of the Army Chief of Staff, forcing the president of the government Antonio Maura to resign afterwards.

[45] According to historian Borja de Riquer, "by tolerating the insubordination of the military in Barcelona, the monarch had left the political system exposed to new pressures and blackmail, which considerably weakened the supremacy of civilian power in the face of militarism".

According to Javier Moreno Luzón, Maura was "convinced that, in a rural and essentially Catholic country like Spain, this opening, controlled if necessary with the reinforcement of repressive mechanisms, would benefit the crown, the Church and the established social order, that is to say, conservative interests".

[73][74] Canalejas' political project, described as "democratic regeneration", "was based on a complete nationalization of the monarchy, in line with the English or Italian experiences"[75] and his government program was typical of the liberal interventionism that "conceived the state as the main modernizing agent of the country".

The abandonment of isolation by the socialists with the formation in November 1909 of the republican-socialist conjunction which brought its general secretary Pablo Iglesias to the Congress of Deputies stimulated the rapid expansion of the PSOE and above all of the UGT union, while the majority anarcho-syndicalist workers' current was consolidated with the birth in 1910 of the National Confederation of Labor.

Finally, Maura did not go to Barcelona, as Cambó expected, and only the deputies of the Catalanist League, the Republicans, the reformists of Melquíades Álvarez and the socialist Pablo Iglesias attended, who approved the formation of a government "which embodied and represented the sovereign will of the country"[121] and which would preside over the elections to the Constituent assembly.

[125] For Santos Julia, the key to the failure was that the Defence Juntas, which the socialists thought they had "essential coincidences" with, sided with the established order, and not only did they not lead any revolution, but they were fully employed in the repression —"neither did the soldiers form sóviets with the workers, in the Russian manner, but in general they obeyed their bosses", Moreno Luzón points out—.

On the same day of Maura's intervention, December 12, 1918, Cambó wrote a letter to the King bidding him farewell and justifying the withdrawal from the Courts of the great majority of Catalan deputies and senators as a sign of protest for the rejection of the Statute, a gesture that was very much frowned upon by the dynastic parties.

The Romanones government opted for negotiation[163] but had to give in to pressure from the employers, who demanded an iron fist and found valuable allies in the Captain General of Catalonia Joaquín Milans del Bosch and king Alfonso XIII.

The latter were led by the ex-policeman Manuel Bravo Portillo, hired by the Employers' Federation, who formed an extensive and well-organized gang composed of criminals and corrupt trade unionists, who carried out the first assassinations of CNT militants and leaders.

[172] Although at the beginning he promoted negotiation to achieve social peace, Dato returned to repressive politics after the assassination of the Count of Salvatierra, former civil governor of Barcelona during the government of Sánchez de Toca, by an anarchist group.

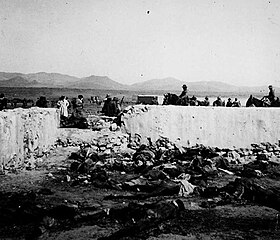

[177] After a leave of absence in Madrid where he received numerous expressions of support from the people, the government and the King, Fernandez Silvestre resumed the advance in May 1921, but this time he encountered the resistance of the Rifian tribes led by Abd el-Krim, from the Beni Urriaguel cabila, located further west.

[186] General Picasso presented his report on the "disaster of Annual" which was devastating since in it he denounced the fraud and corruption that had taken place in the administration of the protectorate of Morocco, as well as the lack of preparation and the improvisation of the commanders in the conduct of the military operations, without safeguarding the governments that had not provided the Army with the necessary material means.

[191] The government of "liberal concentration" presided by Manuel García Prieto announced its intention to advance in the process of responsibilities —in July 1923 the Senate granted the supplication to be able to prosecute General Berenguer since he had parliamentary immunity as he was a member of that Parliament—.

[202] Thus, in addition to re-establishing "social peace", the other objective assigned to the new provincial and local military authorities was to "regenerate" public life by putting an end to the cacique networks, once the "oligarchy" of the politicians of the day had already been dislodged from power.

[216] As the historian Ángeles Barrio has pointed out, "the popularity that the success of the African campaign had given Primo de Rivera allowed him to take a step forward in the continuity of the regime, to return the army to the barracks and to undertake a civilian phase of the Directory.

In fact, on December 13, 1925, Primo de Rivera formed his first civilian government, although the key posts —Presidency, occupied by himself, Vice-Presidency and Interior, by Severiano Martínez Anido, and War by Juan O'Donnell, Duke of Tetuán— were reserved for military personnel.

The civilians belonged to the Unión Patriótica, and among them stood out "the rising stars of corporate authoritarianism: José Calvo Sotelo [a former "maurista" who in the previous two years had occupied the General Directorate of Local Administration] in Finance, Eduardo Aunós in Labor and the Count of Guadalhorce in Public Works".

[223] On September 13, 1926, the third anniversary of the coup d'état that brought him to power, Primo de Rivera held an informal plebiscite to show that he had popular support and thus pressure the King to accept his proposal to convene an unelected Consultative Assembly.

Thus the Dictatorship sponsored the voyage of the Plus ultra, a seaplane piloted by Commander Ramón Franco, which left Palos de la Frontera on January 22, 1926, and arrived in Buenos Aires two days later, after a stopover in the Canary and Cape Verde Islands.

[238] Ángeles Barroso places it a little earlier, at the end of 1927, when with the constitution of the National Consultative Assembly it became clear that Primo de Rivera, in spite of the fact that from the beginning he had presented his regime as "temporary", had no intention of returning to the situation prior to September 1923.

[241] Between the two attempts came the so-called Prats de Molló plot, a failed invasion of Spain from French Catalonia led by Francesc Macià and his party Estat Catalá, and in which Catalan anarcho-syndicalist groups of the CNT collaborated.

[260] On August 17, 1930, the so-called Pact of San Sebastián took place in the meeting promoted by the Republican Alliance in which apparently (since no written minutes were taken) the strategy to put an end to the Monarchy of Alfonso XIII and to proclaim the Second Spanish Republic was agreed upon.

[37] On February 13, 1931, King Alfonso XIII put an end to the "dictablanda" of General Berenguer and appointed Admiral Juan Bautista Aznar as the new president, after unsuccessfully trying to get the liberal Santiago Alba and the conservative "constitutionalist" Rafael Sánchez Guerra (who met with the members of the "revolutionary committee" that were in prison to ask them to participate in his cabinet, which they refused to do: "We have nothing to do or say with the Monarchy", Miguel Maura replied).