Evolution of mammalian auditory ossicles

The event is well-documented[1] and important[2][3] academically as a demonstration of transitional forms and exaptation, the re-purposing of existing structures during evolution.

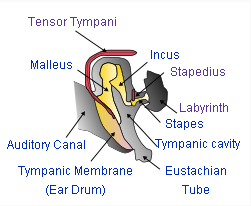

The shortened columella connected to these bones to form a kinematic chain of three ossicles, which serve to amplify air-sourced fine vibrations transmitted from the eardrum and facilitate more acute hearing in terrestrial environments.

Following on the ideas of Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1818), and studies by Johann Friedrich Meckel the Younger (1820), Carl Gustav Carus (1818), Martin Rathke (1825), and Karl Ernst von Baer (1828),[5] the relationship between the reptilian jaw bones and mammalian middle-ear bones was first established on the basis of embryology and comparative anatomy by Karl Bogislaus Reichert (in 1837, before the publication of On the Origin of Species in 1859).

[7][8] The discovery of the link in homology between the reptilian jaw joint and mammalian malleus and incus is considered an important milestone in the history of comparative anatomy.

[9] Work on extinct theromorphs by Owen (1845), and continued by Seeley, Broom, and Watson, was pivotal in discovering the intermediate steps to this change.

[12] During embryonic development, the incus and malleus arise from the same first pharyngeal arch as the mandible and maxilla, and are served by mandibular and maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve.

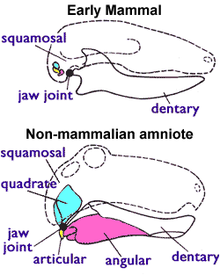

Paleontologists therefore use the ossicles as distinguishing bony features shared by all living mammals (including monotremes), but not present in any of the early Triassic therapsids ("mammal-like reptiles").

All non-mammalian amniotes use this system including lizards, crocodilians, dinosaurs (and their descendants the birds) and therapsids; so the only ossicle in their middle ears is the stapes.

[25][26] In basal members of the 3 major clades of amniotes (synapsids, eureptiles, and parareptiles) the stapes bones are relatively massive props that support the braincase, and this function prevents them from being used as part of the hearing system.

[28][29] During the Permian and early Triassic the dentary of therapsids, including the ancestors of mammals, continually enlarged while other jaw bones were reduced.

This suggests a plausible source of evolutionary pressure: with these small bones in the middle ear, a mammal has extended its range of hearing for higher-pitched sounds which would improve the detection of insects in the dark.

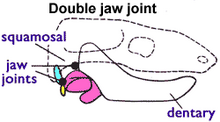

A partial middle ear formed by the departure of postdentary bones from the dentary, and happened independently in the ancestors of monotremes and therians.

The second step was the transition to a definite mammalian middle ear, and evolved independently at least three times in the ancestors of today's monotremes, marsupials and placentals.

[41][42] Researchers now hypothesize that the definitive mammalian middle ear did not emerge any earlier than the late Jurassic (~163M years ago).

[43] A more recent analysis of Teinolophos concluded that the trough was a channel for the large vibration and electrical sensory nerves terminating in the bill (a defining feature of the modern platypus).

[44] A recently discovered intermediate form is the primitive mammal Yanoconodon, which lived approximately 125 million years ago in the Mesozoic era.