Reptile

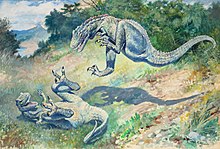

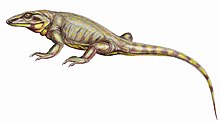

The earliest known eureptile ("true reptile") was Hylonomus, a small and superficially lizard-like animal which lived in Nova Scotia during the Bashkirian age of the Late Carboniferous, around 318 million years ago.

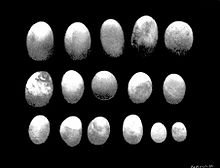

Most reptiles are oviparous, although several species of squamates are viviparous, as were some extinct aquatic clades[6] – the fetus develops within the mother, using a (non-mammalian) placenta rather than contained in an eggshell.

Extant reptiles range in size from a tiny gecko, Sphaerodactylus ariasae, which can grow up to 17 mm (0.7 in) to the saltwater crocodile, Crocodylus porosus, which can reach over 6 m (19.7 ft) in length and weigh over 1,000 kg (2,200 lb).

In the 13th century, the category of reptile was recognized in Europe as consisting of a miscellany of egg-laying creatures, including "snakes, various fantastic monsters, lizards, assorted amphibians, and worms", as recorded by Beauvais in his Mirror of Nature.

Linnaeus, working from species-poor Sweden, where the common adder and grass snake are often found hunting in water, included all reptiles and amphibians in class "III – Amphibia" in his Systema Naturæ.

This was not the only possible classification scheme: In the Hunterian lectures delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons in 1863, Huxley grouped the vertebrates into mammals, sauroids, and ichthyoids (the latter containing the fishes and amphibians).

According to Goodrich, both lineages evolved from an earlier stem group, Protosauria ("first lizards") in which he included some animals today considered reptile-like amphibians, as well as early reptiles.

Thus his Sauropsida included Procolophonia, Eosuchia, Millerosauria, Chelonia (turtles), Squamata (lizards and snakes), Rhynchocephalia, Crocodilia, "thecodonts" (paraphyletic basal Archosauria), non-avian dinosaurs, pterosaurs, ichthyosaurs, and sauropterygians.

The biological traits listed by Lydekker in 1896, for example, include a single occipital condyle, a jaw joint formed by the quadrate and articular bones, and certain characteristics of the vertebrae.

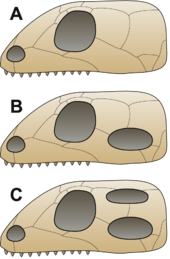

[16] The synapsid/sauropsid division supplemented another approach, one that split the reptiles into four subclasses based on the number and position of temporal fenestrae, openings in the sides of the skull behind the eyes.

[16]Despite the early proposals for replacing the paraphyletic Reptilia with a monophyletic Sauropsida, which includes birds, that term was never adopted widely or, when it was, was not applied consistently.

In 1988, Jacques Gauthier proposed a cladistic definition of Reptilia as a monophyletic node-based crown group containing turtles, lizards and snakes, crocodilians, and birds, their common ancestor and all its descendants.

[32][needs update] The results place turtles as a sister clade to the archosaurs, the group that includes crocodiles, non-avian dinosaurs, and birds.

[35][36][37] A series of footprints from the fossil strata of Nova Scotia dated to 315 Ma show typical reptilian toes and imprints of scales.

[3] Very shortly after the first amniotes appeared, a lineage called Synapsida split off; this group was characterized by a temporal opening in the skull behind each eye giving room for the jaw muscle to move.

The phylogenetic placement of other main groups of fossil sea reptiles – the ichthyopterygians (including ichthyosaurs) and the sauropterygians, which evolved in the early Triassic – is more controversial.

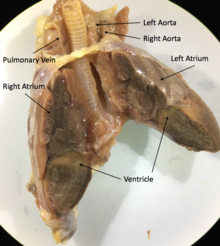

This variation in blood flow has been hypothesized to allow more effective thermoregulation and longer diving times for aquatic species, but has not been shown to be a fitness advantage.

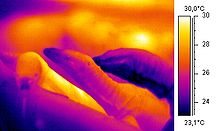

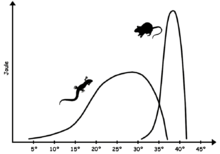

[73] Modern non-avian reptiles exhibit some form of cold-bloodedness (i.e. some mix of poikilothermy, ectothermy, and bradymetabolism) so that they have limited physiological means of keeping the body temperature constant and often rely on external sources of heat.

By using temperature variations in their surroundings, or by remaining cold when they do not need to move, reptiles can save considerable amounts of energy compared to endothermic animals of the same size.

[80] Lower food requirements and adaptive metabolisms allow reptiles to dominate the animal life in regions where net calorie availability is too low to sustain large-bodied mammals and birds.

Crocodilians have evolved a bony secondary palate that allows them to continue breathing while remaining submerged (and protect their brains against damage by struggling prey).

[44] Today, turtles are the only predominantly herbivorous reptile group, but several lines of agamas and iguanas have evolved to live wholly or partly on plants.

In turtles and crocodilians, the male has a single median penis, while squamates, including snakes and lizards, possess a pair of hemipenes, only one of which is typically used in each session.

The earliest documented case of viviparity in reptiles is the Early Permian mesosaurs,[121] although some individuals or taxa in that clade may also have been oviparous because a putative isolated egg has also been found.

Larger lizards, like the monitors, are known to exhibit complex behavior, including cooperation[126] and cognitive abilities allowing them to optimize their foraging and territoriality over time.

[131] Sea turtles have been regarded as having simple brains, but their flippers are used for a variety of foraging tasks (holding, bracing, corralling) in common with marine mammals.

[135] Aided by the reptiles' capacity for remaining motionless for long periods, the camouflage of many snakes is so effective that people or domestic animals are most typically bitten because they accidentally step on them.

In the shingleback skink and some species of geckos, the tail is short and broad and resembles the head, so that the predators may attack it rather than the more vulnerable front part.

Farming has resulted in an increase in the saltwater crocodile population in Australia, as eggs are usually harvested from the wild, so landowners have an incentive to conserve their habitat.

[176] Turtles and tortoises are increasingly popular pets, but keeping them can be challenging due to their particular requirements, such as temperature control, the need for UV light sources, and a varied diet.

B = Synapsid,

C = Diapsid

(1) eggshell, (2) yolk sac, (3) yolk (nutrients), (4) vessels, (5) amnion , (6) chorion , (7) air space, (8) allantois , (9) albumin (egg white), (10) amniotic sac, (11) crocodile embryo, (12) amniotic fluid