Respiratory droplet

[4] These droplets can contain infectious bacterial cells or virus particles they are important factors in the transmission of respiratory diseases.

They can also be artificially generated in a healthcare setting through aerosol-generating procedures such as intubation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), bronchoscopy, surgery, and autopsy.

[6] Similar droplets may be formed through vomiting, flushing toilets, wet-cleaning surfaces, showering or using tap water, or spraying graywater for agricultural purposes.

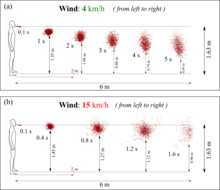

[9] Advanced Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) showed that at wind speeds varying from 4 to 15 km/h, respiratory droplets may travel up to 6 meters.

[10][11] A common form of disease transmission is by way of respiratory droplets, generated by coughing, sneezing, or talking.

[6] Ambient temperature and humidity affect the survivability of bioaerosols because as the droplet evaporates and becomes smaller, it provides less protection for the infectious agents it may contain.

[8] German bacteriologist Carl Flügge in 1899 was the first to show that microorganisms in droplets expelled from the respiratory tract are a means of disease transmission.

In the early 20th century, the term Flügge droplet was sometimes used for particles that are large enough to not completely dry out, roughly those larger than 100 μm.

[11][23] He developed the Wells curve, which describes how the size of respiratory droplets influences their fate and thus their ability to transmit disease.