Restriction enzyme

[12] The phenomenon was first identified in work done in the laboratories of Salvador Luria, Jean Weigle and Giuseppe Bertani in the early 1950s.

[18] In 1970, Hamilton O. Smith, Thomas Kelly and Kent Wilcox isolated and characterized the first type II restriction enzyme, HindII, from the bacterium Haemophilus influenzae.

[19][20] Restriction enzymes of this type are more useful for laboratory work as they cleave DNA at the site of their recognition sequence and are the most commonly used as a molecular biology tool.

[21] Later, Daniel Nathans and Kathleen Danna showed that cleavage of simian virus 40 (SV40) DNA by restriction enzymes yields specific fragments that can be separated using polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, thus showing that restriction enzymes can also be used for mapping DNA.

[22] For their work in the discovery and characterization of restriction enzymes, the 1978 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Werner Arber, Daniel Nathans, and Hamilton O.

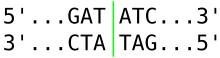

[27] Restriction enzymes recognize a specific sequence of nucleotides[2] and produce a double-stranded cut in the DNA.

The mirror-like palindrome is similar to those found in ordinary text, in which a sequence reads the same forward and backward on a single strand of DNA, as in GTAATG.

Naturally occurring restriction endonucleases are categorized into five groups (Types I, II, III, IV, and V) based on their composition and enzyme cofactor requirements, the nature of their target sequence, and the position of their DNA cleavage site relative to the target sequence.

[32][33][34] DNA sequence analysis of restriction enzymes however show great variations, indicating that there are more than four types.

Cleavage at these random sites follows a process of DNA translocation, which shows that these enzymes are also molecular motors.

These enzymes are multifunctional and are capable of both restriction digestion and modification activities, depending upon the methylation status of the target DNA.

The cofactors S-Adenosyl methionine (AdoMet), hydrolyzed adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and magnesium (Mg2+) ions, are required for their full activity.

Type IIE restriction endonucleases (e.g., NaeI) cleave DNA following interaction with two copies of their recognition sequence.

[29] Type III restriction enzymes (e.g., EcoP15) recognize two separate non-palindromic sequences that are inversely oriented.

[43] These enzymes contain more than one subunit and require AdoMet and ATP cofactors for their roles in DNA methylation and restriction digestion, respectively.

Type III enzymes are hetero-oligomeric, multifunctional proteins composed of two subunits, Res (P08764) and Mod (P08763).

They require the presence of two inversely oriented unmethylated recognition sites for restriction digestion to occur.

[36][45] Type IV enzymes recognize modified, typically methylated DNA and are exemplified by the McrBC and Mrr systems of E.

[35] Type V restriction enzymes (e.g., the cas9-gRNA complex from CRISPRs[46]) utilize guide RNAs to target specific non-palindromic sequences found on invading organisms.

[55][56] In 2013, a new technology CRISPR-Cas9, based on a prokaryotic viral defense system, was engineered for editing the genome, and it was quickly adopted in laboratories.

[63][64] Restriction enzymes can also be used to distinguish gene alleles by specifically recognizing single base changes in DNA known as single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).

In a similar manner, restriction enzymes are used to digest genomic DNA for gene analysis by Southern blot.

[68] Artificial restriction enzymes created by linking the FokI DNA cleavage domain with an array of DNA binding proteins or zinc finger arrays, denoted zinc finger nucleases (ZFN), are a powerful tool for host genome editing due to their enhanced sequence specificity.

A 5–7 bp spacer between the cleavage sites further enhances the specificity of ZFN, making them a safe and more precise tool that can be applied in humans.