Revanchism

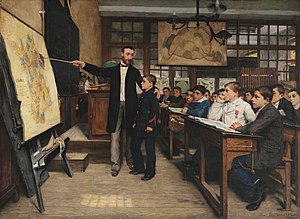

As a term, revanchism originated in 1870s France in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War among nationalists who wanted to avenge the French defeat and reclaim the lost territories of Alsace-Lorraine.

Extreme revanchist ideologues often represent a hawkish stance, suggesting that their desired objectives can be achieved through the positive outcome of another war.

French revanchism was a deep sense of bitterness, hatred and demand for revenge against Germany, especially because of the loss of Alsace and Lorraine following defeat in the Franco-Prussian War.

[1] Georges Clemenceau, of the Radical Republicans, opposed participation in the scramble for Africa and other adventures that would divert the Republic from objectives related to the "blue line of the Vosges" in Alsace-Lorraine.

After the governments of Jules Ferry had pursued a number of colonies in the early 1880s, Clemenceau lent his support to Georges Ernest Boulanger, a popular figure, nicknamed Général Revanche, who it was felt might overthrow the Republic in 1889.

[5] French revanchism influenced the Treaty of Versailles of 1919 following the end of World War I, which restored Alsace-Lorraine to France and extracted reparations from the defeated Germany.

The movement called for the reincorporation of Alsace-Lorraine, the Polish Corridor and the Sudetenland (see Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia—parts of the Austrian Empire and Austria-Hungary until its dismemberment after World War I).

[6] Greek revanchism refers to the political sentiment or movement advocating for the restoration or reclaiming of territories historically or culturally once associated with Greece, but currently under the control of other states.

Stemming from unresolved territorial disputes, Greek revanchism often manifests in nationalist rhetoric, diplomatic tensions, and occasional military confrontations.

[7] While Greek revanchism has influenced foreign policy decisions and public discourse, it remains a contentious and complex issue in the broader context of regional geopolitics and international relations.

During the Crimean War in 1853 to 1856, the Allied nations initiated talks with Sweden to allow troop and fleet movements through Swedish ports to be used against Russia.

In 1865, as the American Civil War ended, Maximilian "was actively recruiting Confederate refugees to colonize northern Mexico and bring their slaves with them.

[20] During the interwar period, the Argentine fascist ideology Nacionalista and organizations such as the Alliance of Nationalist Youth openly supported plans to annex Uruguay, Paraguay, Chile and some southern and eastern parts of Bolivia, which they claimed belonged to Argentina via past territories of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata.

The use of the ideology by Justice and Development Party has mainly supported a greater influence of Ottoman culture in domestic social policy which has caused issues with the secular and republican credentials of modern Turkey.

117/2021 approving the "strategy of de-occupation and reintegration of the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol", complementing the activities of the Crimean Platform.