Reversible addition−fragmentation chain-transfer polymerization

[4] Macromonomers were known as reversible chain transfer agents during this time, but had limited applications on controlled radical polymerization.

[6] RAFT is one of the most versatile methods of controlled radical polymerization because it is tolerant of a very wide range of functionality in the monomer and solvent, including aqueous solutions.

Typically, a RAFT polymerization system consists of: A temperature is chosen such that (a) chain growth occurs at an appropriate rate, (b) the chemical initiator (radical source) delivers radicals at an appropriate rate and (c) the central RAFT equilibrium (see later) favors the active rather than dormant state to an acceptable extent.

The process is also suitable for use under a wide range of reaction parameters such as temperature or the level of impurities, as compared to NMP or ATRP.

The R group must be able to stabilize a radical such that the right hand side of the pre-equilibrium is favored, but unstable enough that it can reinitiate growth of a new polymer chain.

All other products arise from (a) biradical termination events or (b) reactions of chemical species that originate from initiator fragments, denoted by I in the figure.

[9] There are a number of steps in a RAFT polymerization: initiation, pre-equilibrium, re-initiation, main equilibrium, propagation and termination.

In the example in Figure 5, the initiator decomposes to form two fragments (I•) which react with a single monomer molecule to yield a propagating (i.e. growing) polymeric radical of length 1, denoted P1•.

This may undergo a fragmentation reaction in either direction to yield either the starting species or a radical (R•) and a polymeric RAFT agent (S=C(Z)S-Pn).

This is a reversible step in which the intermediate RAFT adduct radical is capable of losing either the R group (R•) or the polymeric species (Pn•).

Re-initiation: The leaving group radical (R•) then reacts with another monomer species, starting another active polymer chain.

The pre-equilibrium and re-initiation steps are completed very early in the polymerization meaning that the major product of the reaction (the RAFT polymer chains, RAFT-Pn), all start growing at approximately the same time.

The forward and reverse reactions of the main RAFT equilibrium are fast, favoring equal growth opportunities amongst the chains.

[13] During RAFT synthesis, some ratios between reaction components are important and usually can be used to control or set the desired degree of polymerization and polymer molecular weight.

As the degassing is decoupled from the polymerization, initiator concentrations can be reduced, allowing for high control and end group fidelity.

With Enz-RAFT, polymerizations do not require prior degassing making this technique convenient for the preparation of most polymers by RAFT.

The technique was developed at Imperial College London by Robert Chapman and Adam Gormley in the lab of Molly Stevens.

RAFT polymerization has been used to synthesize a wide range of polymers with controlled molecular weight and low polydispersities (between 1.05 and 1.4 for many monomers).

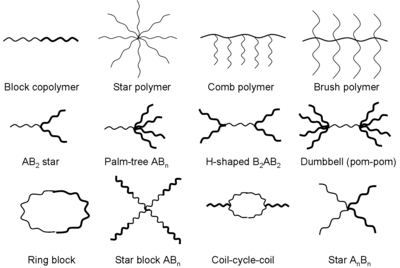

Additionally, the RAFT process allows the synthesis of polymers with specific macromolecular architectures such as block, gradient, statistical, comb, brush, star, hyperbranched, and network copolymers.

Using a compound with multiple dithio moieties (often termed a multifunctional RAFT agent) can result in the formation of star, brush and comb polymers.

[18] Due to its flexibility with respect to the choice of monomers and reaction conditions, the RAFT process competes favorably with other forms of living polymerization for the generation of bio-materials.

As of 2014, the range of commercially available RAFT agents covers close to all the monomer classes that can undergo radical polymerization.

[11] RAFT agents can be unstable over long time periods, are highly colored and can have a pungent odor due to gradual decomposition of the dithioester moiety to yield small sulfur compounds.

The presence of sulfur and color in the resulting polymer may also be undesirable for some applications; however, this can, to an extent, be eliminated with further chemical and physical purification steps.